Analysis Of The Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH) Drug Pipeline & Market: The M&A And Commercial Landscape

By Mavra Nasir, Ph.D., Crystal Hsu, and Peter Bak, Ph.D., Back Bay Life Science Advisors

In Part 1 and Part 2 of this three-part series, we covered the varied complexities of NASH driving an extremely challenging development landscape, along with the growing prevalence of NASH that has the life sciences industry in a race to develop a successful asset.

In this last part of the series, we cover the M&A and commercial landscape implications, including historical and future deal trends, challenges in developing a successful commercial strategy, and what to watch out for as the NASH industry continues to reach new milestones.

NASH Deals And Transactions

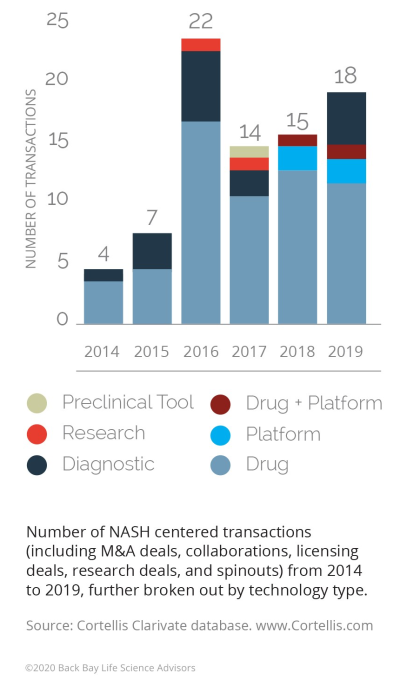

Big Pharma, including Gilead, Novartis, and Allergan, have turned their business development attention to NASH in recent years, with a flurry of activity in 2016 (with 22 deals in 2016, up from seven in 2015).1 At publication, the most significant deal in this space is Allergan’s acquisition of Tobira Therapeutics and its two assets for NASH, for a total deal value of $1.7 billion (19x Tobira’s valuation, 2016).

Figure 1: NASH transactions by year and technology, 2014-20191

Several other deals in the same year were driven by the need for companies to adapt as they encountered obstacles in development.

- There has been an increase in using diagnostics to identify the appropriate patient population that may be amenable for a therapy. This has become increasingly important as therapies fail in broader NASH populations. Additionally, clinical trials are currently using liver biopsy-based tests, which are invasive, expensive, and potentially risky for patients (e.g., bleeding, perforation, infection) and are a challenge for trial recruitment.2

- There is an increasing trend in collaborations between pharmaceutical companies to develop combination therapies, as a monotherapy is likely to post modest or equivocal data and, therefore, will not be an effective therapy. This is due to NASH’s complex pathophysiology (oxidant stress, inflammation activation, fibrogenesis, microbiome, increased intestinal permeability, immune cell mechanisms, etc.) that results in heterogeneity of phenotypes.

- Novartis’ Global Development Unit Head (Immunology, Hepatology and Dermatology) Eric Hughes has stated that they “want to collaborate with multiple partners” to “target different pathways in NASH with a broad array of therapies as an essential strategy to bring the best treatments to patients.”3 For example, in Phase 2 trials, Novartis’ Cenicriviroc did not demonstrate a resolution of NASH but did demonstrate improvement in fibrosis. While it is continuing to be studied as a monotherapy in Phase 3, there is an ongoing Phase 2 trial assessing it in combination with Pfizer’s FXR agonist Tropifexor.

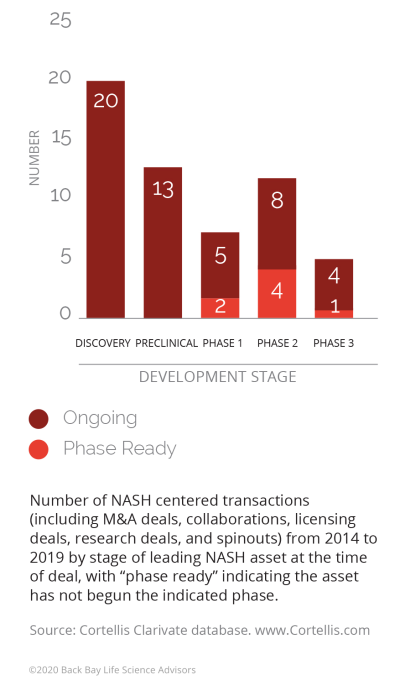

Moving forward, there are factors that will impact M&A activity volume in both directions. There could be a slowdown of deal activity in the near term, as many of the larger players have placed their bets on the most promising early-stage assets (over half of the transactions in the past five years were for discovery/preclinical assets) and are waiting for their initial bets to “play out.” However, approval and success of obeticholic acid (OCA) could reinvigorate it as commercial entities look for a fast follower advantage.

Figure 2: NASH transactions by phase, 2014-2019

Market Access

The challenges of successfully developing and launching a NASH drug do not end in the clinic; questions remain on the optimal commercial strategy for these novel assets, especially around pricing and market access.

- Large patient population: Given a large patient population, including the potential of a substantial undiagnosed patient population, payers will likely ensure novel branded medications are being used in appropriate patient populations via prior authorizations that ensure appropriate diagnostic and staging criteria have been considered.

- Lack of analogs: There are currently no approved products for NASH and, therefore, no pricing benchmarks for pipeline assets.

- Likelihood of combination therapies: Due to the complexity of NASH, an effective treatment regimen is likely to be a combination approach, which will make it difficult for any single therapy to be priced at a significant premium.

- Uncertainty of real-world clinical benefits: It is unclear how surrogate endpoints utilized in clinical trials will translate to real-world clinical impact, which may drive payers to implement stricter restrictions (as demonstrated by some of the pricing challenges PCSK9s encountered when launched in CV disease, further explained below).

Balancing the trade-off between price and volume will determine the success of future NASH therapies. Developers are asking whether the best strategy is to lower price in order to gain access to a broader patient population or to price higher and only have access to restricted subpopulations.

The commercial risk of a faulty pricing strategy has been demonstrated by proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors in cardiovascular disease. When Repatha (evolocumab; Amgen/Astellas) and Praluent (alirocumab; Sanofi/Regeneron) launched in 2015, they were priced at $14,000 annually per patient, which was a significant premium compared to the standard of care generic statins (<$50 annual cost). The pricing reflected the products’ robust data in lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C). However, due to the absence of cardiovascular outcomes trial (CVOT) and direct data of additional clinical benefit, payers restricted utilization to the most high-risk dyslipidemia patients. This resulted in significantly lower uptake than projected, and even with new CVOT data demonstrating reduction of risk in heart attacks, stroke, and death, restrictions remained. Considering this, Amgen reduced the price of Repatha by 60% to $5,850 annual list price in 2018. While Sanofi and Regeneron were able to negotiate a contract with Express Scripts to be placed on its formulary’s preferred tier, Medicare Part D patients still struggled to pay high out-of-pocket co-pay costs. Eventually, they reduced Praluent’s list price to match Repatha’s list price.4

As Intercept prepared for what would be a 2020 launch of OCA, much attention was paid to its pricing and market access strategy. Beyond the clinical questions regarding the safety/efficacy profile, Intercept will have to navigate pricing strategically, given OCA is marketed for treatment of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) under the trade name Ocaliva. As an orphan disease with an estimated prevalence in the range of 100,000 to 150,000,5 Ocaliva commands a premium price with an annual wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) of $80,000 in the U.S.

Given the disparity between the size of the two patient populations—NASH is estimated at ~260 times the size of the PBC population—it is unlikely payers would agree to that price point for NASH even with restricted access for biopsy-confirmed patients. Indeed, Wall Street analysts project a range of potential pricing bands for OCA from $10,000 to $30,000, much closer in line with therapies marketed for highly prevalent cardiovascular diseases.

While it is common to look to analog markets and products when determining price, value-based pricing considerations are increasingly common. These analyses consider the potential price of a drug in the context of clinical benefit and impact on life span and quality of life, relative to current alternatives. These analyses are benchmarked to the value of the drug relative to one incremental quality of life year (QALY) gained (e.g., a cost threshold in which the drug extends one year of life in good health). In light of the REGENERATE trial data, the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) developed a perspective on an acceptable price point for the asset in NASH.6 Based on a QALY threshold of $100,000 (e.g., an appropriate price if one year of life in good health is valued at $100,000), ICER arrived at a cost-effectiveness threshold of $17,150. Interestingly, if only used in F3 patients, this rises to $19,780, highlighting the greater cost and need in more severe patients. Not surprisingly, if priced at the current price in PBC, a QALY would have to be valued over $1 million for OCA to be cost-effective.

Given the stark disparity in market dynamics between NASH and PBC, it is no surprise that Intercept has been considering a careful market access approach to commercialize the same molecule at different prices for two diseases. The company has communicated to the street it is considering a dual brand strategy for OCA in PBC and NASH. Pharma has used this approach in the past to sell the same active pharmaceutical ingredient at two separate price points in two different indications.

The most well-known example of this approach is Pfizer’s sildenafil, marketed as Viagra, a treatment for erectile dysfunction requiring a ~50 mg tablet per dose, and Revatio, a sildenafil oral suspension for pulmonary arterial hypertension requiring 5 to 20 mg three times per day. However, with the same formulation launched for NASH and PBC, Intercept will need to ensure dosing, pill size, and packaging are sufficiently differentiated that the likely lower-priced NASH drug is not substituted for the higher-priced Ocaliva brand in PBC.

To alleviate payer concerns, Intercept is going to great lengths to communicate that it is focusing marketing efforts on hepatologists and GI specialists, which will allow them to target a circumscribed NASH population and prevent widespread utilization. Given the size of the NASH market, payers have prospectively communicated they may establish significant utilization/approval criteria prior to reimbursing OCA.7 However, in multiple quarterly updates, the company has communicated it will ensure the drug is not inappropriately prescribed, in that its commercial strategy will be to target the ~15,000 hepatologists and gastroenterologists that have a large NASH patient load in order to treat the 1.5 million (out of 19 million NASH patients) with fibrosis and cared for by specialists with NASH experience.8 Intercept released market research that shows many physicians would be comfortable identifying patients with early fibrosis with non-invasive testing and imaging—the implication being that biopsy could be a requirement by payers to allow access.8

Summary

- The economic and health burden of the growing NASH population in the U.S. is a matter of immense concern, given that NASH is expected to become the leading indication for liver transplant in the U.S. in the next few years.

- Currently there are no disease-specific approved drugs for NASH, with multiple historical failures creating a substantial unmet need for the patient population.

- Given the complex and poorly understood nature of NASH, there are a variety of mechanisms of actions under investigation by biopharma.

- The first wave of NASH drugs are all expected to be monotherapy treatments, with the FDA’s current refusal to grant obeticholic acid accelerated approval intensifying the race to the finish line for several late-stage agents.

- Based on current clinical trial guidelines, the FDA requires biopsy confirmed success in at least one of the following endpoints to grant accelerated approval: 1) improvement of ≥1 stage in fibrosis with no worsening of NASH; 2) improvement in NASH resolution with no worsening of fibrosis. In contrast to the FDA, the EMA draft guidance requires efficacy in both endpoints in a co-primary fashion, which may complicate timely approvals in the five major European markets (Germany, France, Spain, Italy, U.K.).

- On top of the regulatory challenges, the first wave of NASH therapies will face unchartered reimbursement territory and any novel therapy may encounter strict prior authorization from payers, tied to the enrollment criteria of pivotal trials.

- With a flurry of deal activity in NASH during the 2016-2017 timeframe, recent clinical setbacks may have a cooling effect on the deal-making. However, approval and success of OCA could reinvigorate the deal space as commercial entities look for a fast follower advantage.

- Key remaining areas of unmet need and future development include successful development of non-invasive diagnostics to monitor NASH progress and evaluate response to treatment, combination regimens to manage NASH and the associated comorbidities, and more clinical trials focusing on the severe F4 patients.

References:

- Cortellis. www.cortellis.com.

- DeLegge, M. The difficulties in recruiting NASH patients for clinical trials, and how we can solve them. The Liver Line https://liverline.com/the-difficulties-in-recruiting-nash-patients-for-clinical-trials-and-how-we-can-solve-them-44339dd6f6e7 (2017).

- Novartis. Novartis announces clinical collaboration with Pfizer to advance the treatment of NASH. Press Release https://novartis.gcs-web.com/Novartis-announces-clinical-collaboration-with-Pfizer-to-advance-the-treatment-of-NASH (2018).

- Sanofi. Sanofi and Regeneron to lower net price of Praluent® (alirocumab) Injection in exchange for straightforward, more affordable patient access for Express Scripts patients. Press Release http://www.news.sanofi.us/2018-05-01-Sanofi-and-Regeneron-to-lower-net-price-of-Praluent-R-alirocumab-Injection-in-exchange-for-straightforward-more-affordable-patient-access-for-Express-Scripts-patients (2018).

- Lu, M. et al. Increasing Prevalence of Primary Biliary Cholangitis and Reduced Mortality With Treatment. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. (2018) doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2017.12.033.

- Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Obeticholic Acid for the Treatment of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis with Fibrosis. https://icer-review.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/ICER_NASH_Draft_Evidence_Report_03192020.pdf (2020).

- Bell, J. On the path to patients, NASH drugs may hit a payer roadblock. BioPharma Dive https://www.biopharmadive.com/news/nash-drugs-payer-pushback-price-diet-exercise/554245/ (2019).

- Intercept Pharma. Intercept NASH Commercial Day. https://ir.interceptpharma.com/static-files/076ed33d-3f9a-4605-a5ca-ed39c1695beb (2019).

About The Authors:

Mavra Nasir, Ph.D., consultant at Bay Life Science Advisors, supports strategic engagements across a range of therapeutic areas including rare diseases, hematology/oncology, and metabolic diseases for biopharma and medtech companies of all sizes. She has leveraged her scientific background and analytical expertise to help provide meaningful solutions to drug developers. Nasir joined Back Bay after receiving her Ph.D. in quantitative biomedical sciences from Dartmouth College. She has published research in non-invasive infectious disease diagnostics using advanced mass spectrometry and machine learning and presented at multiple national and international conferences. Nasir received her BSc in biological sciences from McGill University and MS in bioinformatics from New York University. Connect with her at info@bblsa.com.

Mavra Nasir, Ph.D., consultant at Bay Life Science Advisors, supports strategic engagements across a range of therapeutic areas including rare diseases, hematology/oncology, and metabolic diseases for biopharma and medtech companies of all sizes. She has leveraged her scientific background and analytical expertise to help provide meaningful solutions to drug developers. Nasir joined Back Bay after receiving her Ph.D. in quantitative biomedical sciences from Dartmouth College. She has published research in non-invasive infectious disease diagnostics using advanced mass spectrometry and machine learning and presented at multiple national and international conferences. Nasir received her BSc in biological sciences from McGill University and MS in bioinformatics from New York University. Connect with her at info@bblsa.com.

Crystal Hsu, consultant at Back Bay Life Science Advisors, guides biotech, pharmaceutical, and medical device companies across an array of therapeutic areas. She has expertise in global pricing and market access, launch and go-to-market strategy, profit and revenue optimization, and landscape assessments for life science companies. Hsu has experience in evaluating market opportunities for life science companies in China. She graduated from Emory University’s Goizueta Business School with a BBA in finance and strategy & management consulting. Connect with her at info@bblsa.com.

Crystal Hsu, consultant at Back Bay Life Science Advisors, guides biotech, pharmaceutical, and medical device companies across an array of therapeutic areas. She has expertise in global pricing and market access, launch and go-to-market strategy, profit and revenue optimization, and landscape assessments for life science companies. Hsu has experience in evaluating market opportunities for life science companies in China. She graduated from Emory University’s Goizueta Business School with a BBA in finance and strategy & management consulting. Connect with her at info@bblsa.com.

Peter Bak, Ph.D., SVP at Back Bay Life Science Advisors, has more than 10 years of experience with a broad range of research approaches — cellular, molecular and biochemical — and fields, from immunology and infection through oncology. He leads a diverse portfolio of projects with a focus on liquidity planning and positioning, strategic franchise building, M&A, and licensing strategy and buy-side diligence. Bak’s research career in immuno-oncology began at Dartmouth Medical School, where he received his Ph.D. in microbiology and immunology, and continued at MIT, as an American Cancer Society Postdoctoral Fellow at the Koch Institute of Integrative Cancer Research. He holds a BA in biology from The College of the Holy Cross. Connect with him at info@bblsa.com.

Peter Bak, Ph.D., SVP at Back Bay Life Science Advisors, has more than 10 years of experience with a broad range of research approaches — cellular, molecular and biochemical — and fields, from immunology and infection through oncology. He leads a diverse portfolio of projects with a focus on liquidity planning and positioning, strategic franchise building, M&A, and licensing strategy and buy-side diligence. Bak’s research career in immuno-oncology began at Dartmouth Medical School, where he received his Ph.D. in microbiology and immunology, and continued at MIT, as an American Cancer Society Postdoctoral Fellow at the Koch Institute of Integrative Cancer Research. He holds a BA in biology from The College of the Holy Cross. Connect with him at info@bblsa.com.