Trends In FDA FY2022 Inspection-based Warning Letters

By Liz Oestreich, Madeleine Giaquinto, and Kalah Auchincloss

The COVID-19 pandemic continued to impact FDA’s inspection activities in FY2022 despite efforts to shift more of the agency’s focus beyond the public health emergency. This article will analyze FDA warning letters issued in FY2022 (Oct. 1, 2021, to Sept. 30, 2022). Specifically, this article will review certain inspection-based warning letters issued to drug manufacturers and offer reflections on current trends and predictions for the upcoming year.

FDA inspection activities began to normalize in 2022, despite years of COVID-19 related disruptions. FDA initially paused all inspections in March 2020 due to the COVID-19 public health emergency, but soon thereafter resumed limited domestic inspections in July 2020 based on priority. The agency then resumed prioritized foreign inspections in October 2020. COVID-19 variants continued to delay the regular course of inspection activities throughout 2021 and into 2022, including a short return to only mission critical inspections from Dec. 29, 2021, to Feb. 7, 2022. Although most of FY2022 saw a return to regular domestic inspection operations, FDA did not resume all foreign inspections until April 2022.

Based on our review, we observed some continued trends from the COVID-19 era, as well as signs that the agency may be expanding its focus beyond the pandemic, shifting its operations back to a more regular course. FDA notably took an interest in repeat violations observed during inspections, OTC drug products including hand sanitizers, responsibilities for contract manufacturers, and testing of incoming components and raw materials. This article discusses each of these themes before examining what this may mean for FDA’s drug GMP enforcement focus in 2023 and beyond.

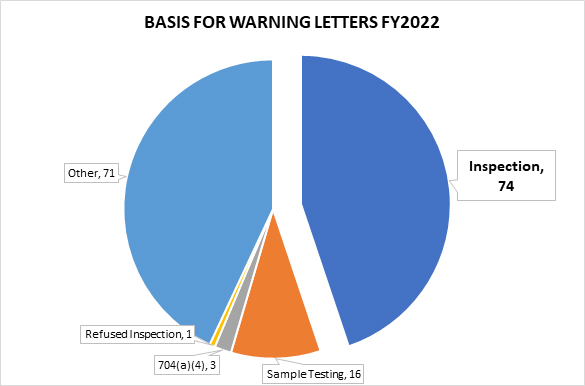

In FY2022, FDA issued 165 drug product warning letters. Of the 165, 74 were based on observations from an on-site inspection, 16 letters stemmed from tested samples, and three from a records request under section 704(a)(4) of the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) (referred to as 704(a)(4) requests in this article).1 The remainder of the warning letters were generally the result of review of product labels, registration materials, and/or websites.2

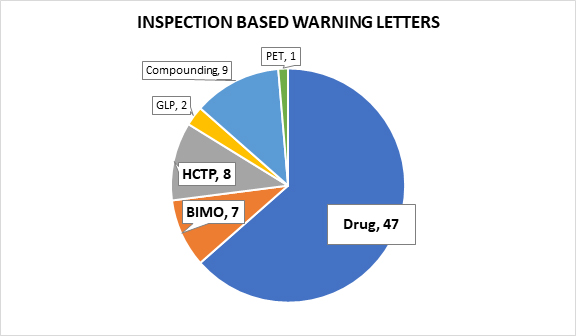

Of the 74 letters following on-site inspections, seven followed bioresearch monitoring (BIMO) inspections,3 eight focused on human cell, tissue, or cellular products (HCTP),4 two followed good laboratory practice (GLP) inspections,5 nine were issued to pharmaceutical compounding firms,6 and one was issued to a PET drug manufacturer.7 This article excludes warning letters following GLP inspections, those issued to pharmaceutical compounding firms, and the warning letter issued to the PET drug manufacturer in an effort to focus our analysis on the most relevant 62 warning letters prompted by violations observed during an on-site inspection.

BIMO Inspections

BIMO inspections are designed to evaluate the conduct of FDA-regulated research to ensure the quality and integrity of data submitted to the agency in support of marketing applications and to protect the rights, safety, and welfare of human subjects. In FY2022, the FDA primarily observed failures associated with study execution and inappropriate enrollment of human subjects. The majority of the letters were issued to firms within the U.S. (five). One warning letter was also issued to a firm in Ukraine and one was issued to a firm in Canada. Three of the seven warning letters cited failure to conduct investigations according to an investigational plan pursuant to 21 CFR 312.60.8 Specifically, the FDA voiced concern about investigational plan deviations to enroll subjects who did not meet eligibility criteria, which jeopardizes subjects’ safety and welfare and raises concerns about the validity and integrity of the data collected.9 FDA also found lack of adherence to safety-related testing requirements by Joseph A. Zadra for failing to complete tests at specific timepoints. Smitha C. Reddy also failed to follow protocols for randomizing specific groups and appropriately blinding studies to prevent bias among staff.

Two letters cited failure to submit an Investigational New Drug (IND) application for clinical investigations with an investigational new drug, per 21 CFR 312.2(a).10 Two of the seven letters found improper usage of an institutional review board (IRB), as set forth in 21 CFR 56, for review and approval of the proposed clinical study protocol.11 Additionally, two letters included observations for failure to obtain informed consent from participants in accordance with 21 CFR 5012 and failure to retain documentation for two years pursuant to 21 CFR 312.13

Human Cell and Tissue Products (HCTPs)

The FDA issued eight warning letters to U.S. firms manufacturing HCTPs in FY2022. Of the eight, four observed insufficient evaluation or testing for communicable disease in samples.14 The FDA’s website includes information about tests that are currently recommended to adequately and appropriately reduce the risk of transmission of relevant communicable disease agents and diseases, including a complete list of donor screening assays and specific requirements for donor testing. This is a top consideration in the agency’s approach to HCTP safety and availability for all patients but especially for fertility-focused products for which donor history is relevant to preventing sexually transmitted disease.

The remaining four letters cite 21 CFR 1271.3(f)(1), the requirement for minimal manipulation of HCTPs, and warn companies with products that have been processed to the point where the original characteristics have been altered.15 The statute defines minimal manipulation of HCTP products to mean (1) processing that does not alter the original relevant characteristics of the tissue relating to the tissue’s utility for reconstruction, repair, or replacement, and (2) for cells or non-structural tissues, processing that does not alter the relevant biological characteristics of cells or tissues.16 If a product is more than minimally manipulated, it does not qualify as an HCTP, and is instead subject to premarket review and approval as a drug or biologic under a biologics license application (BLA).17

The agency also cited five of the eight HCTP manufacturers for failure to establish written procedures designed to prevent microbiological contamination. All concern the failure to validate processes for products purporting to be sterile. The failure to establish and follow written procedures has been a theme across all inspection-based warning letters; the agency typically views these types of issues as “low-hanging fruit” indicative of an immature quality system. Interestingly, these warning letters do not include a recommendation to engage a third-party consultant to assist with GMP compliance as is included in most inspection-based drug warning letters analyzed below.

Drug Products

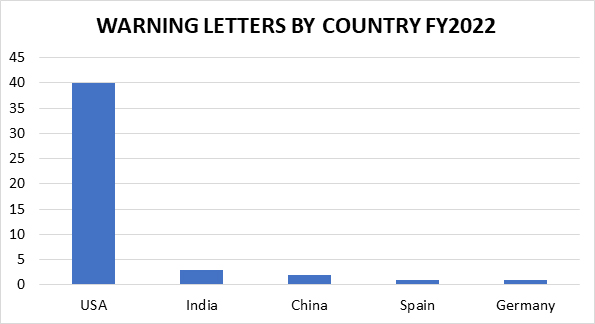

The remaining 47 inspection-based warning letters issued to drug manufacturers are less geographically diverse than in years past, with three firms located in India, two in China, and one each in Germany and Spain. The remaining 40 warning letter recipients are in the U.S. (including one from Puerto Rico). This is not surprising, given the limited ability of FDA to conduct foreign inspections for a significant portion of FY2022.

A majority of the letters went to OTC manufacturers (32 in total), which includes the sole homeopathic product manufacturer, as well as one company that manufactures OTC drugs and medical devices.18 The remaining warning letters went to six finished prescription drug manufacturers and nine API manufacturers.19 FDA also noted that three recipients were contract testing laboratories (one contract testing lab tested OTC products, one tested API, and one tested finished pharmaceuticals).20

Notably, 16 warning letters were for hand sanitizer products, and another five were for topical skin lightening products.21 As we discuss later in the article, the focus on hand sanitizers is directly related to the COVID-19 pandemic and FDA’s regulatory efforts to expand the available supply of hand sanitizer while ensuring the safety of the product.

Other general trends identified across analyzed warning letters are also worth highlighting. For example, a large majority of warning letters (42) included a recommendation for the retention of an expert consultant to assist firms in their remediation efforts, a trend that has become increasingly standard in recent years.

Moreover, although inspections in 2021 and 2022 were far less numerous than in non-pandemic years, investigators were prompt in issuing letters. All but one of the 47 warning letters were issued within 12 months of the last day of an inspection.22 Of these, the shortest turnaround time was just shy of four months, with the inspection concluding on Nov. 19, 2021, and receipt of the warning letter occurring on March 14, 2022.23 This timeframe is impressive given the agency’s pandemic workload.

Finally, although much has changed since 2019 and early 2020, FDA hasn’t forgotten about violations that predate the pandemic, with 19 of the 47 warning letters specifically calling out repeat observations.

Key Emerging Themes

Component Testing

Concerns surrounding component product quality was a particular theme in FY2022 warning letters. Overall, 13 warning letters included component testing observations: nine hand sanitizer product warning letters included this language, as well as one skin lightening product and three non-hand sanitizer OTC products. The agency observed companies relying on certificates of analysis (COAs) for identification of product components and raw materials (without first establishing the reliability of those COAs), rather than performing the appropriate testing to ensure the product met required acceptance criteria for use in manufacturing. The agency noted that those firms relying on COAs had no assurance that the product conforms with appropriate specifications for identity, strength, quality, and purity.

For example, the Premier Trends LLC letter articulated the need to test incoming API and components of a product. In it, FDA explained:

“Though you receive raw materials with a certificate of analysis from your suppliers, you have not performed appropriate incoming analysis of component lots upon receipt, including confirming the identity prior to use in production of your finished drug product. You also relied on your supplier's certificate of analysis without establishing the reliability of your component supplier's test analyses at appropriate intervals.”24

Not surprisingly, this observation was frequently included in warning letters for hand sanitizer products, specifically due to the presence of methanol and other harmful impurities found in products tested at the border. For example, language was included in the letter to Yusef Manufacturing Laboratories for failing to test API used for its hand sanitizer product:

“You failed to adequately test your incoming components for identity before using the components to manufacture your over-the-counter (OTC) drug products. Additionally, you relied on [COAs] from unqualified suppliers for specifications such as purity, strength, and quality. By not adequately analyzing your components for identity, purity, strength, and quality, you failed to ensure your incoming components meet appropriate specifications.”25

Contract Manufacturing Responsibility and Accountability

Another theme observed in FY2022 warning letters was the close attention paid to contract manufacturers and contract testing laboratories, a possible product of the agency’s more recent whole supply chain focus. Overall, letters issued in FY2022 drive home the twin requirements that: (1) contract manufacturers are subject to cGMPs and quality requirements just like other manufacturers; and (2) the product sponsor is responsible for the finished product and has a duty to oversee its contractors and suppliers. The agency included contract manufacturing or testing language in 18 warning letters.

Notably, 11 of those 18 warning letters included a separate section for this information at the bottom of the letter. The title for this section varied, but the placement of this language at the end of a warning letter, similar to recommendations to engage a third-party cGMP expert or calling out specific concerns surrounding data integrity, shows the agency’s desire to clearly communicate the significance of this message, including the need for effective quality agreements.

For example, Sanitizer Supply produced hand sanitizers as a contract manufacturer. FDA found that Sanitizer Supply failed to test incoming components and also failed to validate and establish the reliability of their component supplier’s test analyses at appropriate intervals (21 CFR 211.84(d)(1) and (2)). In this case, even though Sanitizer Supply is a contract manufacturer, FDA points out that they are still required to manufacture drugs in conformance with cGMP, regardless of any agreements with product owners. FDA included the following paragraph emphasizing this point at the end of its letter to Sanitizer Supply.

“Responsibilities as a Contractor

Drugs must be manufactured in conformance with cGMP. The FDA is aware that many drug manufacturers use independent contractors such as production facilities, testing laboratories, packagers, and labelers. The FDA regards contractors as extensions of the manufacturer.

You are responsible for the quality of drugs you produce as a contract facility regardless of agreements in place with application sponsors and product owners. You are required to ensure that drugs are made in accordance with section 501(a)(2)(B) of the FD&C Act for safety, identity, strength, quality, and purity. See the FDA’s guidance document Contract Manufacturing Arrangements for Drugs: QualityAgreements at https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/contract-manufacturing-arrangements-drugs-quality-agreements-guidance-industry.”26

This reminder also appears in the letters sent to Sanitor Corporation, NDAL Mfg Inc., Vitae Enim Vitae Scientific Inc., and Sterling Pharmaceutical Services, among others. In the case of Sterling, the firm, acting as a contract manufacturer, received findings related to sterility failures. Specific incident investigations into contamination risks, which included microorganisms recovered from ISO 5 areas, routinely identified poor aseptic behaviors among manufacturing personnel, despite the company’s findings that there was a “very low” contamination risk posed to drug products.

Warning letters to other firms contained language emphasizing the firm’s responsibility for oversight of its contractors, such as the letter to Specialty Process Labs LLC stating:

“Your firm’s quality unit (QU) failed to perform routine QU functions to ensure drug manufacturing operations were adequate. For example, your QU failed to:

- Establish and maintain adequate evaluation procedures for third-party laboratories that are utilized for finished drug testing, such as fat analysis, inorganic iodides and residual solvents. Your quality unit has not qualified or evaluated any of the contract laboratories used for these tests.”27

Failure To Cooperate With The FDA For Inspection

Interestingly, two warning letters were issued to companies that failed to cooperate with FDA for the purpose of facility inspection. Mexican firm Glicerinas Industriales, S.A de C.V., refused entry to FDA (via phone) for a planned inspection at their manufacturing site scheduled to occur in May 2022 and, as a result, received a warning letter that drugs manufactured at the facility were adulterated.28 A domestic contract testing lab, Green Wave Analytical LLC, also failed to cooperate with FDA. Green Wave delayed FDA’s on-site inspection for three days by falsely representing that the firm did not perform cGMP testing of finished drug products under contract. FDA’s warning letter to Green Wave states that because of the partial refusal, its products are adulterated.29

In addition, Global Sanitizers was subject to an on-site inspection after it twice refused to respond to a 704(a)(4) records request. FDA noted the refusals in the warning letter, reminding the firm that failure to respond to a 704(a)(4) request is a prohibited act under the FD&C Act, and then cited the company for several significant cMPG violations based on the on-site inspection.30

FDA expends significant resources to complete inspections in a timely manner and utilizes a risk-based site selection model to prioritize on-site inspections, thus it is not surprising that firms that were unwilling to cooperate with the agency received warning letters.31

Heightened FDA Scrutiny On Two Key Product Types

Hand Sanitizer Products

Hand sanitizer products continued to be an area of heightened interest in FY2022, again demonstrating the agency’s continued focus on safeguarding the public against COVID-19-related products. As threats of the public health emergency continued and many returned to daily in-person activities, the public relied on masking and hand sanitization as a way to limit transmission of the disease. Hand sanitizer products flooded the market beginning in 2020 and continuing into 2022.

An extensive review of FDA’s approach to the regulation of hand sanitizers during the pandemic as a whole is beyond the scope of this article. Suffice it to say that after issuing a guidance providing flexibility for manufacturing hand sanitizer to meet growing public demand, FDA began to notice a significant uptick in safety concerns with such products, including contamination with methanol, a toxic and potentially lethal substance that resulted in several poisonings and deaths.32 While many hand sanitizer warning letters were issued following detention and testing at the U.S. border, 16 warning letters were issued to hand sanitizer manufacturers after an on-site inspection.

Artnaturals33 stands out as an example of FDA’s diligence in ensuring violative products are removed from the market. Artnaturals offered a variety of hand sanitizing products that included a scent-free hand sanitizer product found to be contaminated with benzene, acetaldehyde, and acetal impurities. In this case, FDA repeatedly attempted to reach the manufacturer regarding violative sample results. After the company failed to respond, FDA issued a public notification. The company subsequently voluntarily recalled the product in October 2021. They were inspected in the months following the recall. In light of the concerns regarding contamination and impurities, numerous other manufacturers of hand sanitizers were issued warning letters with citations for failure to adequately test components or finished drug product to ensure they met standards for identity, strength, and purity.34

Global Sanitizers was similarly unresponsive to two attempts to request records under 704(a)(4) and other information from the company before their Las Vegas, NV, facility was inspected in February 2021. Global Sanitizer served as a repackager and relabeler of bulk consumer hand sanitizing products. FDA tested product samples from the facility and found two products contained methanol. Medically Minded Hand Sanitizer Gel Antimicrobial Formula contained an average of 58% methanol, and Medically Minded Hand Sanitizer Gel Antimicrobial with Vitamin E & Moisturizer contained an average of 32% ethanol and an average of 7.4% methanol. Both products were labeled to contain 70% of the active ingredient ethanol. As noted above, methanol is toxic and can cause dermatitis and transdermal absorption with systemic toxicity when absorbed by the skin and can be more injurious if consumed orally.

American Cleaning Solutions is another blatant example of cGMP failures by a domestic hand sanitizer manufacturer. This company manufactures insecticides and industrial cleaners in addition to hand sanitizing products and failed to establish and follow written procedures for cleaning and maintenance of equipment (21 CFR 211.67(b)). FDA noted in the warning letter that “[i]t is unacceptable as a matter of CGMP to continue manufacturing drugs using the same equipment that you use to manufacture pesticides or other non-pharmaceutical products due to the risk of cross-contamination.”35 FDA also found that the active ingredient isopropanol was substituted wholly or in part with ethanol and cited the company for inadequate release testing, among other violations.

In addition to GMP failures, unapproved drug claims were another common observation made among violative hand sanitizer products. For example, the Spartan Chemical Company’s hand sanitizer product claims to be “effective in shortening the duration of infection and preventing infection or disease from the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19.”36 The agency found this language concerning because it goes beyond merely describing the general intended use of a topical antiseptic.

In short, FDA acted quickly and decisively when it came to hand sanitizer products in FY2022, particularly those containing acetaldehyde, which appears to be genotoxic (and potentially carcinogenic), methanol, and other impurities that may pose risk to consumers and those that made unapproved drug claims.

Skin Lightening Products

Another interesting trend in FY2022 was FDA’s focus on products in the beauty industry. Specifically, topical OTC products like sunscreens and skin lightening products were significantly represented, with five warning letters issued to companies manufacturing skin lightening products.37 This may signal that the agency intends to shift toward products that may have flown under the radar during the pandemic, especially OTC drugs popularized by advertising and promotion. These products caused serious and permanent skin damaged and often made unapproved drug claims.

Notably, a warning letter sent to Generitech Corporation encompasses many of the key themes of FY2022. FDA found that the firm’s “quality system for investigations is inadequate and does not ensure consistent production of safe and effective products.”38 It also found that it failed to conduct adequate testing for components and API used for the production of the skin lightening products, including the salicylic acid API used in the product. Instead, the firm relied on COAs from suppliers. Without adequate testing, there is no assurance that a final product conforms to appropriate specifications. Additionally, and significantly, this was a repeat observation from an untitled letter sent in January 2014.

Predictions For 2023 And Beyond

As our analysis demonstrates, in FY2022 COVID-19 remained an issue for FDA, although the agency has shown signs that it is shifting toward regular business — for example, circling back on repeat offenses, holding firms accountable up and down drug supply chains, and enforcing against non-COVID-19 related products, such as skin bleaching agents.

We expect COVID to continue to have effects on enforcement and inspections in 2023, but we also predict that the agency will operate under more typical conditions in 2023. This almost certainly means more oversight of foreign entities now that COVID-era restrictions have been lifted and more foreign inspections are taking place. Given the pandemic inspection pauses of the past few years, it’s possible we may see an uptick in inspection-based warning letters in the years to come.

That said, certain policy changes and shifts in enforcement priorities made during the pandemic are likely here to stay. For example, we expect FDA to continue to focus on OTC products and to pay close attention to enforcement activities across different types of manufacturers, including contract testing labs and CMOs, as part of its broader efforts to enhance entire supply chain resiliency and to prevent drug shortages. And perhaps most notably, we anticipate FDA will seek to understand lessons learned from the pandemic and how to apply those lessons moving forward, including how to best leverage alternatives to on-site inspections, such as 704(a)(4) records requests, voluntary remote regulatory assessments, mutual reliance on inspectional findings from foreign authorities, product sampling and testing, and other tools. The agency will also need to implement the inspection-related provisions of the Food and Drug Omnibus Reform Act (FDORA), attached to the FY2023 omnibus appropriations bill that was enacted in December 2022. Many of the FDORA provisions relate to FDA’s use of alternative tools.

Although we have centered this article on inspection-based drug warning letters, it is worth noting that several warning letters falling outside that narrow scope shed light on the potential areas of focus for FY2023. For example, in FY2022 FDA issued the first warning letter for a delta-8 THC product, in the midst of the exploding market for cannabis- and hemp-derived products.39 FDA will also almost certainly continue to monitor websites, online labeling, and marketing materials, as we saw this year, and issue warning letters citing unapproved drug charges (for both COVID- and non-COVID-related products). In FY2022 FDA sent warning letters to three companies marketing skin tag and mole removing products that are unapproved new drugs. Notably, one of the three was issued to online retailer giant Amazon, which could signal further attempts to regulate similar large third-party sellers.40

Finally, although not a warning letter, a recently issued untitled letter again points to the agency’s focus on whole supply chain accountability and resiliency. The letter, issued to Valisure, LLC on Dec. 5, 2022, cited the analytical laboratory for problems with its contract testing services, which are aimed at fulfilling drug manufacturers’ cGMP requirements, as well as for violations under the Drug Supply Chain Security Act41 (DSCSA). Although it came after our FY22 timeframe, the letter is worth mentioning because, in this case, the agency held the firm responsible for potentially causing downstream cGMP violations due to their inadequate testing methods. Moreover, the letter notably calls out the firm’s DSCSA violations, an area that has yet to see much enforcement focus to-date. With DSCSA requirements coming into full effect in November 2023, greater emphasis on similar violations moving forward is another reason manufacturers should be aware of their responsibilities to the drug supply chain as a whole.

References/Notes

- Cosmo Bio Co., Ltd., Dr Retter Ec Wladyslaw Retter, and Guangzhou Orchard Aromatherapy & Skin Care Co., Ltd. (all OTC manufacturers) received warning letters based on a 704(a)(4) records request.

- One company, Glicerinas Industriales, S.A. de C.V., received a warning letter on June 13, 2022, for refusing to allow FDA entry to conduct an on-site inspection.

- Warning letters issued following BIMO inspections include Daniel C. Tarquinio, Daniel Fred Goodman, Joseph A. Zadra, Richard J. Obiso, Sabine S. Hazan, Smitha C. Reddy, Vasyl Melnyk

- BioLab Sciences, Inc.; Surgenex LLC; Cooper Institute; Smart Surgical, Inc. dba Burst Biologics; OsteoLife Biomedical I LLC; Re-Gen Active Lab, Inc.; Zhang Medical P.C. dba New Hope Fertility Center; and Vitti Labs, LLC.

- This includes GLP Warning Letters issued to Toxikon Corporation/LabCorp Bedford LLC on Feb. 10, 2022, and Valley Biosystems on Aug. 3, 2022.

- Texas Longhorn RX, LLC; Hybrid Pharma, LLC; New Vitalis, LLC dba New Vitalis Pharmacy; Age Management Institute Santa Barbara; Med Shop Total Care, Inc.; Advanced Nutriceuticals, LLC dba The Guyer Institute of Molecular Medicine; Empower Clinic Services, LLC dba Empower Pharmacy; Sagent Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; and Innoveix Pharmaceuticals Inc.

- Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Inc.

- Daniel C. Tarquinio, D.O./Center for Rare Neurological Diseases, Joseph A. Zadra, M.D., and Smitha C. Reddy, M.D./ACRC Studies, LLC.

- Daniel C. Tarquino, D.O./Center for Rare Neurological Diseases, April 5, 2022.

- Richard J. Obiso, PhD dba Avila Herbals, LLC and Daniel Fred Goodman, M.D./Goodman Eye Center.

- Richard J. Obiso, PhD dba Avila Herbals, LLC and Sabine S. Hazan, M.D. See also 21 CFR 312.66.

- Daniel Fred Goodman, M.D./Goodman Eye Center

- Vasyl Melnyk, M.D.

- Cooper Institute, OsteoLife Biomedical, LLC, Smart Surgical, Inc dba Burst Biologics, and Zhang Medical P.C. dba New Hope Fertility Center.

- BioLab Sciences, Inc., Re-Gen Active Lab, Inc., Surgenex LLC and Vitti Labs, LLC.

- 21 CFR 1271.3(f).

- 21 CFR 1271.10; 21 CFR 1271.3.

- OTC homeopathic drug manufacturer Sterling Pharmaceutical Services, LLC and Dental Technologies Inc., an OTC drug and device manufacturer, are included in this category.

- This includes Fagron Group B.V., which operates as a repackager and relabeler of API product.

- Miami Univ (contract testing API); Green Wave (contract testing finished Rx); Accu-Biochem (contract testing OTC); Sterling (contract manufacturer).

- Sanitor Corporation manufactures both hand sanitizer and skin lightening products and thus is included in the count for both categories.

- Custom Research Labs Inc., an OTC manufacturer of hand sanitizer products, received a warning letter on July 8, 2022, approximately 13 months following the end of an inspection on June 4, 2021.

- Ultra Seal Corporation’s facilities in New Paltz, NY, were inspected between Aug. 16, 2021, and Nov. 19, 2021, and a warning letter was issued on March 14, 2022.

- FDA Warning Letter to Premier Trends LLC, Mar. 14, 2022

- FDA Warning Letter to Yusef Manufacturing Laboratories, Feb. 8, 2022

- FDA Warning Letter to Sanitizer Supply LLC, Sept. 2, 2022.

- FDA Warning Letter to Specialty Process Labs, LLC, May 3, 2022.

- FDA Warning Letter to Glicerinas Industriales, S.A. de C.V., Jun. 13, 2022.

- FDA Warning Letter to Green Wave Analytical LLC, Aug. 19, 2022

- FDA Warning Letter to Global Sanitizers LLC, Nov. 8, 2021.

- The agency recently updated is guidance on Circumstances that Constitute Delaying, Denying, Limiting or Refusing a Drug or Device Inspection. The new draft was issued in December 2022 to include device firms as well as drug facilities. See, https://www.fda.gov/media/163927/download.

- See e.g., https://www.fda.gov/drugs/coronavirus-covid-19-drugs/hand-sanitizers-covid-19 and https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-updates-hand-sanitizers-consumers-should-not-use

- Virgin Scent Inc. dba Artnaturals.

- See e.g., Yusef; Agropharma Laboratories, Inc.; American Cleaning Solutions; Custom Research Labs Inc.; Fresh Farms LLC; Froggy’s Fog LLC; Sanitizer Supply LLC; and Global Sanitizers LLC.

- FDA Warning Letter to American Cleaning Solutions, Sep. 6, 2022.

- FDA Warning Letter to Spartan Chemical Company, Inc., Dec. 15, 2021.

- The five firms include Monarch PCM, LLC, Sanitor Corporation (which manufacturers both hand sanitizing products and skin lightening products), Generitech Corporation, Clinical Resolution Laboratory Inc., and Bi-Coastal Pharma international.

- FDA Warning Letter to Generitech Corporation, Mar. 1, 2022.

- FDA Issues Warning Letters to Companies Illegally Selling CBD and Delta-8 THC Products, May 4, 2022, https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-issues-warning-letters-companies-illegally-selling-cbd-and-delta-8-thc-products

- FDA Warning Letter to Amazon.com, Inc., Aug. 4, 2022.

- The DSCSA establishes a system for the electronic, interoperable tracking and tracing of certain prescription drugs at the package-level in the U.S. FDA has been implementing DSCSA requirements in a phased manner since the law’s enactment in November 2013. These requirements apply to all trading partners involved in the exchange of prescription drugs along supply chains, including manufacturers, repackagers, distributors, and dispensers.

About The Authors

Liz Oestreich, J.D., is senior vice president of regulatory compliance at Greenleaf Health. She brings more than nine years of regulatory experience and a diverse background of legal, public policy, and non-profit sector knowledge to her position. As a consultant, Oestreich provides strategic guidance on premarket and postmarket issues to drug, medical device, tobacco, and cannabis companies. She earned her J.D. from the University of the District of Columbia, David A. Clarke School of Law, and her B.A. from the University of Arizona.

Liz Oestreich, J.D., is senior vice president of regulatory compliance at Greenleaf Health. She brings more than nine years of regulatory experience and a diverse background of legal, public policy, and non-profit sector knowledge to her position. As a consultant, Oestreich provides strategic guidance on premarket and postmarket issues to drug, medical device, tobacco, and cannabis companies. She earned her J.D. from the University of the District of Columbia, David A. Clarke School of Law, and her B.A. from the University of Arizona.

Madeleine Giaquinto is manager of regulatory affairs at Greenleaf Health, Inc. She provides clients with timely analysis of FDA regulations, policies, and guidance documents and strategic advice on FDA engagement regarding compliance-focused issues and good practice standards for FDA-regulated products. Giaquinto has worked in diverse settings across the life science field, including within legal, nonprofit, government affairs, and public health policy specialties, and has a robust set of skills and knowledge of each as they intersect with regulatory compliance and federal and state healthcare policy matters. She has a B.S. in biology from Georgetown University and a J.D. from George Mason University School of Law. You can connect with her on LinkedIn.

Madeleine Giaquinto is manager of regulatory affairs at Greenleaf Health, Inc. She provides clients with timely analysis of FDA regulations, policies, and guidance documents and strategic advice on FDA engagement regarding compliance-focused issues and good practice standards for FDA-regulated products. Giaquinto has worked in diverse settings across the life science field, including within legal, nonprofit, government affairs, and public health policy specialties, and has a robust set of skills and knowledge of each as they intersect with regulatory compliance and federal and state healthcare policy matters. She has a B.S. in biology from Georgetown University and a J.D. from George Mason University School of Law. You can connect with her on LinkedIn.

Kalah Auchincloss, J.D., M.P.H., is executive vice president of regulatory compliance and deputy general counsel for Greenleaf Health. She has more than 15 years of food and drug legal, policy, and regulatory experience at the FDA, on Capitol Hill, and in the private sector. At Greenleaf, Auchincloss advises pharmaceutical and medical device companies on compliance, policy, and other regulatory issues. Before moving to Greenleaf, Auchincloss spent six years at the FDA in the Commissioner’s Office and in CDER’s Office of Compliance and Office of Regulatory Policy. She earned her J.D. from Georgetown University, her M.P.H. from Harvard University, and her B.A. from Williams College.

Kalah Auchincloss, J.D., M.P.H., is executive vice president of regulatory compliance and deputy general counsel for Greenleaf Health. She has more than 15 years of food and drug legal, policy, and regulatory experience at the FDA, on Capitol Hill, and in the private sector. At Greenleaf, Auchincloss advises pharmaceutical and medical device companies on compliance, policy, and other regulatory issues. Before moving to Greenleaf, Auchincloss spent six years at the FDA in the Commissioner’s Office and in CDER’s Office of Compliance and Office of Regulatory Policy. She earned her J.D. from Georgetown University, her M.P.H. from Harvard University, and her B.A. from Williams College.