The Second Wave Of Biosimilars: New Scenarios, New Rules

By Jose Ignacio Diaz, general manager, Emergpharma

In 2006, the first biosimilar, somatropin (Omnitrope), was approved in Europe. It has been more than a decade since initial reticence about its safety and efficacy has been permanently forgotten, owing to the clinical practice collected. As before with generics, biosimilars are said to be one of the main tools that European governments will use in the coming years to control the pharmaceutical budget.

By July 2020, there were 18 molecules with biosimilars registered in Europe, of which 15 corresponded to 57 products commercialized in the market. Of course, COVID-19 has slowed down the pace of new biosimilar launches, but the EMA still has authorized four biosimilar products this year. Furthermore, there are an additional 16 dossiers under assessment that are expected to be approved in the coming months.[i]

Adoption Curve, Price Erosion, And Excessive Competition

According to data provided by Biopharmalinks,[ii] average penetration of biosimilars in 2019 was 23% in Europe, with strong variations according to the molecule and country. The segment is growing between 5% and 8% annually, notably due to the rapid adoption of anti-TNFs. Based on the results of the Pugartch study,[iii] biologics with the potential of bringing in $2.7 to 5.4 billion are released each year. These biologics, in turn, become opportunities for future biosimilar development.

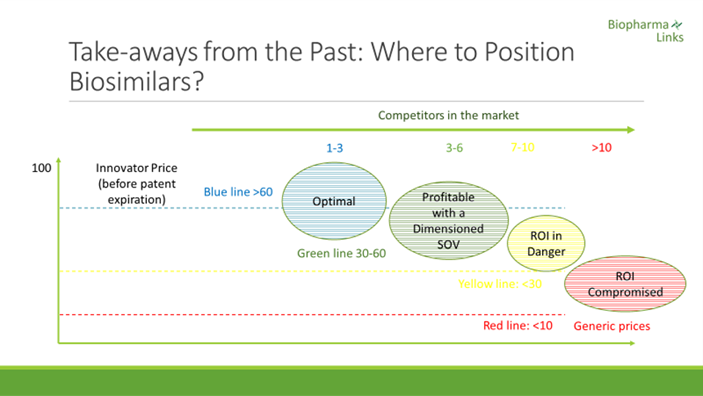

Regarding the impact on price reduction, there are significant differences between molecules and time periods. The number of competitors, nonetheless, is always a key success factor. In recent anti-TNF launches, erosion of the price of the originator reaches a 25% average at the time of entry of the first biosimilar. Following the third biosimilar launch, prices fall below 50%. When the number of competitors achieves or exceeds five — especially in markets where products are strongly dominated by tenders — erosion can reach up to 70% relatively quickly.

If we refer to other categories that have had more time in the market, filgrastim, for example, is being awarded in public auctions at a price equal to 7.5% of the original before the expiration of the patent,[iv] This is a case demonstrating that innovators often choose to turn down a drastic price reduction for their products to avoid being expelled from the market.

Being the first to launch is key in the case of both generics and biosimilars. With this in mind, EU companies that come a year after the first entry capture only 11% of the market share achieved by that of the first generic launched.[v] In the case of biosimilars, the first anti-TNF launched in 2016 captured over 70% share, while the second and third had to settle for 30% to 40% and 5% to 22%, respectively.[vi]

The arrival of what we could call the first “bio patent cliff” has revealed important lessons that should be taken into consideration when selecting new candidates for the second and third waves. In the second wave, there are at least 40 biosimilars of Humira (adalimumab) under development and more than 20 of Remicade (infliximab). It seems obvious that when these products reach the market, prices will be affected considerably. Despite the fact that the market is huge, it is probable that in "the winner takes all" trajectory, a number of companies will have to resign themselves from launching their products or assume the losses by forgoing recovering part of their investments. Experience indicates that considering the theoretical market size and the expiration date of the patent as the only product selection criteria does not seem to be an appropriate strategy.

Differences Between The First And Second Waves Of Biosimilars

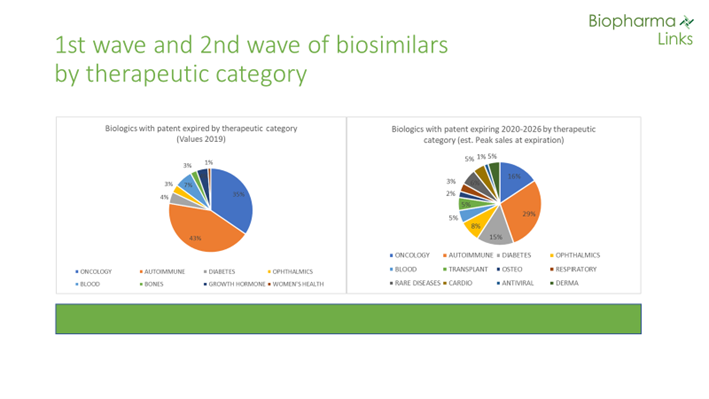

The first wave of biosimilars represented global sales of $70 billion in 2019. In comparison, the total sales of “second-wave” biologicals with expired patents — or patents that will expire in the coming five to six years —is $79 billion. Products in this wave are expected to reach peak sales of more than $100 billion before patent expirations. Moreover, at least 30 molecules in the second wave will reach blockbuster status, ranging from $1 to $12 billion in annual sales. There are no products in this class, however, with the potential to reach the nearly $20 billion achieved yearly by Humira. There are at least two candidates (Keytruda and Opdivo) that may potentially exceed that figure in the third wave (patent expirations expected by the end of the decade).

Regarding therapeutic areas, while 78% of sales in the first wave belong to the categories of oncology and autoimmune diseases, these indications only represent 34% of the total in the second wave. Other therapeutic areas are increasing in importance, such as diabetes and ophthalmic conditions. New categories such as transplantation, cardiovascular, osteoporosis, antiviral, and dermatology are also emerging.

Second Wave Biosimilars Face A Very Different Context

Companies that decided to invest in the development or marketing of biosimilars in the first wave had no experience in this new segment that, despite its obvious risks, still offered undeniable opportunities. As some of the initial reluctance among patients and physicians has faded, other unanticipated problems emerged, such as the proliferation of highly competitive players. The second wave of biosimilars faces a totally different context than the first, as we explain below.

a) Prescribers

Several published studies show that doctors, in general, feel comfortable using biosimilars now that fears of immunogenicity have been clearly disproved by the facts. In reality, the original products themselves have eventually suffered from this problem, as was the case with Cetuximab.[vii] However, in the case of biosimilars, process control has advanced so that any such problems are detected during the registration process and, therefore, do not make it to market.

b) Patients

Health systems providing universal coverage in the EU virtually guarantee access to biological products to anybody, regardless of income level. Therefore, there are no particular incentives for patients to transition from a reference product to a biosimilar, but they trust their doctors to the extent that they are confident and accepted, although this is not always the case. When the patient is an "expert" and frequent user of products such as insulins, routines are developed for years. As such, treatment changes can lead to confusion and generate a negative perception, which can then translate into a “nocebo effect” against the biosimilar product.

c) Payers

The EU health authorities have long understood that the sustainability of the system necessarily requires a drastic and rapid reduction in drug prices once the patent reaches expiration. Not so long ago, the Lehman Brothers crash had accelerated the adoption curve of generics considerably, and the drop in prices has recently reached levels almost immediate to the patent expiration. It took more than six years for oxaliplatin to reach a price below 10% of the original product, while imatinib generics reached it in their first auction in Spain.

In the case of biosimilars, there were a priori reasons that supported a slower price erosion, such as higher entry barriers (production costs, technical difficulties, etc.). However, the considerable growth experienced by biotechnology companies in the Asia Pacific region has changed the situation; in China and India, we have identified more than 500 biosimilars under development. Another classic barrier, the lack of clinical experience, has disappeared thanks to positive real-world evidence. The relative autonomy of prescription, understood as the prohibition of switching at the pharmacy level, was also a determining factor. However, the pragmatism exhibited by some countries, such as the Nordics, and the likely implementation of a much more open substitution law in Germany, could radically change things.

COVID-19 and the impending economic crisis are expected to further accelerate the pragmatism of governments and measurements to promote the use of biosimilars. The current situation has shown movement toward facilitating switching and limiting the autonomy of the prescribing process that will be put in place in the forthcoming years, if not months. In this context, keeping a commercial structure to actively promote and differentiate the products with prescribers will likely not be necessary, especially should the centralized “winner takes all” tender model currently in force in certain nations only prioritize price. Should tenders remain centered only on price, focusing on other elements of differentiation wouldn’t be financially sustainable for biosimilar makers to pursue.

d) Geographic environment

The Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC) for biological products in force for the EU countries allows extended protection conferred by the basic patent for up to five years. Initially designed to protect innovation, the entrance and proliferation of biosimilars have changed the landscape dramatically. At present, European companies can’t initiate the development of a biosimilar until the SPC is over, while competitors from abroad — mostly without a similar regulatory barrier — can get extra time. In some cases, as in India, biosimilar products are allowed to launch in their original markets before entering Europe. As a consequence, European companies are at clear disadvantage to be the first to launch. As mentioned before, launch order is a key success factor. Big pharmaceutical companies have solved the problem by moving manufacturing plants out of Europe, which, in practice, represents a one-way trip due to the associated costs. It is estimated that moving the manufacturing site of a single biological can cost at least $10 million and take between one and a half to two years. Similarly, changing the API producer in the case of complex products can add up to an additional minimum of around 4 million euros.[viii] Although the EMA is evaluating possible measures to correct this imbalance,[ix] its implementation is complex because it affects international trade agreements and may be too late for many midsize companies and startups. At the moment, China and India are the countries leading the development of biosimilars, with 269 and 257 respectively, with the U.S. further behind in third place with 189.[x] This guarantees China and India unquestionable leadership in the forthcoming decade.

e) Competitors’ profiles

Large companies were the ones that bet the most on this segment since the beginning. Teva, Sandoz, and Pfizer (Hospira) were the forerunners with the launches of the first biosimilars. Those companies have recently been joined by Amgen, Mylan, and Fresenius. Sanofi has joined the club with the registration of an insulin as well. Their size and resources provide these companies with the financial muscle to survive and possibly even dominate this segment for years to come.

Indian companies such as Dr. Reddy’s, Aurobindo, Accord, and Glenmark, among others, have acquired great experience in the commercialization of generics in European markets in recent years and see interesting opportunities to incorporate these products into their already extensive portfolios. These companies have an advantage thanks to their cost competitiveness, their commercial efficiency developed after more than a decade in Europe, and the possibility they can start development earlier and test the products in their domestic market.

Two Korean companies, Celltrion and Samsung, have been leading the launch of the first anti-TNF in Europe. With no prior experience in these markets, they have tried two different entry strategies, in both cases with relative success. While Samsung chose to create a joint venture with Biogen (Samsung Bioepis), Celltrion chose to license its products to large companies (Pfizer, MSD) and to regional (Mundipharma) and local (Servier, Kern) champions. Other Korean pharmaceutical companies are ready to enter and some have already closed license agreements, such as Alteogen with Stada and DKSH. Others, such as CKD and Dong AS, have not yet revealed their market access models. Biosimilars are only an intermediate step in their commitment to innovation, and almost all of them are also developing innovative products, although these developments will take longer to see the light of day.

Midsize pharmaceutical companies with regional or local leadership, such as Stada, Mundipharma, Kern, Servier, and Rovi, have selected products that allow them to exploit their ability to communicate with doctors and their knowledge of local markets. In general, except in the case of Rovi, they do not manufacture these products but have arranged out-licensing agreements. Their competitive positions will depend a lot on the degree of differentiation they can maintain with their clients and to what extent their cost structures can compete.

Finally, Chinese companies are for the moment giving priority to their domestic market, but they are always looking at the European and American markets. As commented before, they are the ones with the largest number of biosimilars in development, above India and the U.S. Their main competitive advantage lies in the benefits that the Chinese government provide to any way of innovation in this field. In addition, their professionals have been trained at leading universities and research centers in the world, and the size and growth of their internal market allow them not to depend on success in Europe. In fact, succeeding in developed markets is more a matter of prestige or geopolitics than of short-term profitability. China is also the largest producer of APIs in the world, having about 20% of the market. In the case of biological products, an integrated management of the production process from the preparation of the active ingredients to the final product can become a decisive competitive advantage.

Success Strategies: Selection Of New Biosimilars

Many companies that thought to enter the market in the first wave may now be reevaluating their strategy. Who has more options: the big multinationals, the newcomers such as Indian and Korean companies, or the Chinese companies to come? And what about midsize companies with a strong presence in certain markets? Is there room for everyone in this segment?

The answers are not easy. In a market that is so variable and subject to factors that change all the time, having almost unlimited resources, as is the case of large pharmaceutical companies, makes their options to dominate this market in the mid-term considerably high. However, we have seen how new players, notably Indian and Korean companies, have grabbed a significant market share and, in the case of the former, have emerged victorious in many battles fought in the generics market in Europe. In addition, many of these companies already have a critical mass and market presence that should facilitate a fast penetration. They know the tender channels and mechanisms, and their ability to minimize their costs gives them significant advantages. On the latter, Chinese companies remain a mystery, although their resources to develop a very extensive portfolio and their non-dependence on European markets enable them to spend time learning about these factors and accept losses (if they should occur) as part of the learning curve.

Under these circumstances, it is worth asking whether there are opportunities for midsize companies with regional or local scope. In our opinion, it will depend on their ability to select the right portfolio. In a market dominated by “the winner takes all” model where governments are pressured by a considerable economic crisis post-pandemic, arriving late to an overcrowded market does not make any sense. However, there are opportunities if adequate product selection occurs. It is essential, especially for these companies, to follow criteria that take into account all aspects of the product, including the supply of active ingredients, the manufacturing process optimization, the regulatory path, the evaluation of the treatment paradigm, the expected level of acceptance by doctors and patients, the situation regarding tenders, the expected level of competition, the portfolio synergies and, over all, company resources and objectives. The choice in these cases must be surgical, because failure can affect not only the income statement but the sheer survival of the company.

[i] http://www.gabionline.net/Biosimilars/General/Biosimilars-applications-under-review-by-EMA-July-2020

[ii] www.biopharmalinks.com

[iv] https://www.euskadi.eus/gobierno-vasco/contenidos/anuncio_contratacion/exposakidetza26105/es_doc/es_arch_exposakidetza26105.html

[v] CRA study (2017). A number of studies support the existence of a first mover advantage effect for generic products. See Sharjarizadeh et al (2015), Yu and Gupta (2008), Hollis et al (1991)

[vi] The Impact of Biosimilar Competition in Europe (2017). The report analyzes the impact on volume on two biosimilar therapy classes, Anti-TNF and EPO.

[vii] Li & D’Anjou Pharmacological Significance of Glycosylation in Therapeutic Proteins. APPLIED MICROBIOLOGY & BIOTECHNOLOGY. At 681-82

[viii] The Impact of Biosimilar Competition in Europe (2017). The report analyzes the impact on volume on two biosimilar therapy classes, Anti-TNF and EPO.

[ix] “Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Regulation (EC) No 469/2009 concerning the supplementary protection certificate for medicinal products” https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52018PC0317&from=EN