The First Truly Bionic Chip

About the Chip (Back to Top)

In the chip, the cell acts as an electrical diode, or switch, in a circuit, allowing current to flow through the device at certain voltages. While it had been known for some time that cells could pass current, having a cell function as a diode is a new concept on which the bionic chip relies.

UC Berkeley's new "bionic chip" features a living biological cell successfully merged with chip electronic circuitry for first time. Red and black wires are part of the chip circuitry and the chip is mounted on a plastic holder to make it large enough to hold. Photo credit: UC Berkeley Office of Media Services.

The particular voltage needed to trigger the cell diode differs depending on the cell type, and part of the magic here is that the chip determines the correct voltage. Once known, it acts like a "remote control to a door" according to the designer, UC Berkeley mechanical engineering professor Boris Rubinsky.

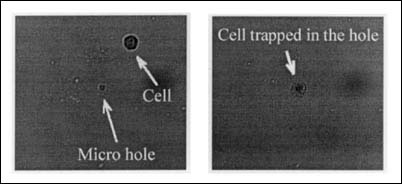

UC Berkeley's bionic chip took three years to build using silicon microfabrication technology. It is transparent, so it can be viewed by a microscope, and measures about one hundredth of an inch across. The cell, which measures only about 20 microns across, sits in a hole in the center of the chip and is kept alive with an infusion of nutrients.

Applications (Back to Top)

"This is important because the door to the living cell has been very important but very difficult for us to open reliably until now without causing any damage to the tissue," said Rubinsky. He envisions that such chips and the elaborate bionic circuitry they might make will someday be used to develop body implants for the treatment of genetic diseases, for example.

Seen through a microscope, a human prostate cancer cell takes up its position as part of electronic circuit in new UC Berkeley bionic chip. Photo credit: Boris Rubinsky and Yong Huang.

Researchers hope eventually they can develop cell-chips tuned for the precise voltage needed to activate different bodily tissues, from muscle to bone to brain. That way, cell-chips could be applied by the thousands to correct a variety of health problems.

"We've brought engineering essentially into the field of biology," said Rubinsky, a professor of mechanical engineering at the University of California, Berkeley, which funded his research. "We can introduce DNA, extract proteins, administer medicines—all without bothering other cells that might be around."

UC Berkeley applied for a patent on the technology last summer and is in the process of licensing it commercially.

The work, which was funded by a UC Berkeley Chancellor's Professorship award, exemplifies the multidisciplinary research that UC Berkeley campus is now sponsoring through its new Health Sciences Initiative.

For more information: Boris Rubinsky, Mechanical Engineering, 6105B Etcheverry Hall, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-1740. Tel: 510-642-8220. Fax: 510-642-6163. Email: rubinsky@me.berkeley.edu.