Single-Use Standardization Starts At Home

By Tyler Menichiello, Chief Editor, Bioprocess Online

Single-use technologies (SUTs) are mainstays in today’s biomanufacturing ecosystem, offering more flexibility, operational efficiency, and reduced COGs compared to traditional stainless-steel systems. However, due to the countless suppliers, systems, and components available to manufacturers, the issue of standardization — or lack thereof — is a growing challenge, not only across the industry, but across organizations’ manufacturing sites.

During a recent Bioprocess Online Live event, “Single-Use Harmonization Needs A Tune Up,” only 7.4% of audience members indicated that their single-use assemblies were standardized across their sites; 37% said they were partially standardized, and 37% said they were not standardized at all. This event featured prominent single-use experts Frank Gillam, Ph.D., director of MSAT at Locus Biosciences; Mark Petrich, Ph.D., VP of technical operations at Krystal Biotech; and Paul Priebe, a single-use consultant that serves as a scientific advisory council member at the Bio-Process Systems Alliance (BPSA) and the ASME BPE subcommittee.

Addressing Internal Interoperability

“In a nutshell, the idea of single-use is that it’s flexible,” said Petrich, but when one company uses multiple suppliers across different sites, it creates an interoperability challenge that can impede this flexibility.

But where does this standardization even start?

These internal standards should encompass every aspect of SUS — the material they’re made of, how they look, how they operate, and how they’re tested. “All of those are important,” Petrich told the audience. Be thoughtful, but don’t overthink it into oblivion. As Petrich has told process engineers in the past, there are certain things where creativity can be applied, and others where creativity should be set aside. For example, a length of tubing with two connectors stretching between two points in a factory. “Why do we have so many designs for that?” he asked rhetorically.

With multiple sites, it’s almost inevitable that setups and SKUs will differ, but both sites should be supplied by the same vendors. For transform assemblies, Petrich said, “I found that we had some success in trying to standardize on designs, on sizes, on materials of construction, [and] how they were used in our facilities, so that that collection could support multiple factories [and] multiple users.”

“Then, those people could focus their creative energies and product expertise on those transformative pieces of the process,” Petrich explained.

Flexibility Is Built On Pre-Validation

The difficult tightrope many small- to mid-size biotech companies walk is that of executing in the present but planning for the future. Lean too far either way, and you may fall off altogether.

“The motivations of a small, clinical company [are] to get to the next round of data, not to worry about making drug product 10 years from now,” said Priebe. Understandably, a lot of decisions get made that work well for today but aren’t great for the long haul, he continued, but it’s worth the investment to plan ahead. This includes thinking about things like equivalency or interchangeability for SUTs.

By pre-qualifying and pre-validating equipment substitutions, companies can avoid headaches down the line in the form of delays and operational disruptions. Petrich uses the example of allowing a 200 L bag to be pre-approved for use in place of a 100 L bag to avoid last-minute deviations during an emergency.

“Nobody wants to do more validation than they have to,” Gillam said, “but I also strongly agree with having some other jumpers at hand that are pre-validated so that when you get in a pickle, you can daisy-chain those things together to get a solution.”

The panelists agreed that this early work should involve team members from the equipment side, the process development side, and especially, from the QA side. Involving QA is critical for demonstrating equivalency between SUT materials, which is a major part of this pre-validation workflow. Priebe suggests taking a risk-based approach, focusing time, energy, and effort on things that have the biggest consequences (e.g., demonstrating equivalency for bulk drug substance bags would require more rigorous validation than would a flush system, where supplier extractables data will likely suffice).

If COVID taught the industry anything, it’s that supply chains can be disrupted — and it doesn’t take a pandemic for your last bag to rip or a delivery to disappear. Mistakes happen, and planning ahead of time to allow for SUT substitutions can be the difference between stalling operations or getting a therapy to patients.

It’s On End Users To Drive Harmonization

The real takeaway message from this event is that broad single-use standardization will not come from the top down. Suppliers are all in competition, and they have no good reason to design interchangeable technologies, at least not until there’s market pressure from buyers to do so.

That’s why standardization needs to begin at home, with end-users. “You reward suppliers that are open and facilitate the establishment of standards and interoperability within your own facility,” Priebe explained.

“We’re better today than we were 20 years ago,” Priebe said. “We used to compete on extractables,” but come May 2026, every supplier will be providing data packages under USP <665>, the first USP standard written specifically for SUT, according to Priebe.

“I am optimistic,” Petrich said. “I see that we’ve made a lot of progress.” In response to an audience question on how suppliers can standardize but also differentiate themselves, Petrich said it’s all about standardizing the basics — aligning them — and letting suppliers differentiate themselves through added bells and whistles.

If end-users are expecting regulators to legislate standards, they may wait ad infinitum. “Regulate yourself to avoid being regulated,” Priebe professed. “You want to be in control of your own destiny.”

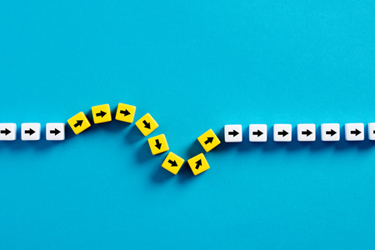

Progress is always slow, but as evidenced by USP <665>, market pressure (e.g., for extractables data) can lead to change. Think about the industry and its parts like a train, barreling full speed on a track. A sudden, sharp turn would derail it catastrophically, but gradual curves over time can shift its course entirely (hopefully, for the better).

If the majority of companies are intentional about setting internal SUS standards, then the market will have no choice but to reflect these standards. “Approach it like you do anything else in your process,” Gillam said. “Design with bracketing risk assessment and consider alternatives in all aspects of supply chain.” That way, end-users can give these SUTs the best chance to deliver on their promise of flexibility.