Real-World Phase-Appropriate Control Lessons For mAb/ADC Manufacturers

By Victor Lien, Ph.D., PMP

Biologics manufacturing is a balancing act between speed and certainty, innovation and control. For mAbs and antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), the stakes are especially high: these therapies are complex, sensitive to process variation, and increasingly central to modern medicine. Over the years, I’ve seen how even the most elegant platform can falter without a control strategy that evolves with the molecule. That’s where phase-appropriate control strategy comes in — not as a checklist, but as a mindset.

This column offers a practical, experience-informed roadmap for implementing control strategies across the development lifecycle by considering what to control as well as when, why, and how to adapt when reality doesn’t follow the playbook.

Why Phase-Appropriate Control Is More Than A Regulatory Expectation

At its core, control strategy is about aligning control intensity with risk and knowledge. In early development, we prioritize patient safety and speed, often leaning on platform processes and broader acceptance criteria. As the molecule matures, so must our controls — tightening specifications, validating critical process parameters (CPPs), and embedding lifecycle thinking into every decision.

But control strategy isn't just a regulatory expectation, it’s a strategic tool. It helps teams avoid over-engineering in Phase 1 and under-preparing for commercialization. It also creates a shared language across chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC); manufacturing science and technology; (MSAT); QA; and regulatory functions, enabling faster decisions and fewer surprises.

The Control Strategy Pyramid: A Living Framework

To visualize how controls evolve, I often use the control strategy pyramid. At the base are raw materials and supplier controls. As we move up, we encounter process parameters, in-process testing, release specifications, and finally, stability and continued process verification (CPV).

- Materials control: Raw materials, media, resins, filters, and supplier agreements ranked by risk.

- Process controls: CPPs, in-process controls, and automation logic.

- In-process testing: Real-time or at-line assays for key quality attributes.

- Release specifications: Identity, purity, potency, safety, and strength.

- Stability and verification: Continued process verification and stability studies.

This pyramid isn’t static. As process understanding deepens, controls can shift upstream. A quality attribute once managed by end-product testing might become an in-process control, reducing redundancy and improving responsiveness. However, that shift only works if we’ve built the data and confidence to support it.

Phase-Specific Priorities: From Speed To Sustainability

Four principles should guide control strategy design:

- Risk-based scaling: Controls should reflect the risk to patient safety and product quality. Early phases emphasize safety. Later phases emphasize consistency.

- Iterative knowledge building: Use data from development, scale-up, and clinical experience to refine controls.

- Lifecycle integration: Control strategies must adapt to new knowledge, scale changes, and regulatory expectations.

- Cross-functional alignment: CMC, QA, regulatory, MSAT, and clinical teams must collaborate so controls are scientifically justified and operationally feasible.

These principles keep the strategy practical and defensible as the program matures.

With these principles in mind, let’s walk through how control strategies evolve across development phases, not as isolated stages, but as a continuum of learning and risk management.

Phase 1: Fit for plant and patient

In Phase 1, the goal is to reach the clinic safely and quickly. We rely on platform processes — standard CHO cell lines, Protein A capture — and accept broader criteria. Controls focus on safety-related attributes, such as aggregation, host cell proteins (HCPs), residual DNA, and for ADCs, gross drug-antibody ratio (DAR), and free drug levels.

But even here, we can plant seeds for future robustness, trend our data, and flag anomalies, even within limits. These early signals often foreshadow later issues.

Phase 2: Characterization and range finding

Phase 2 is where we shift from “does it work?” to “how does it work?” We run design-of-experiments (DoE), build scale-down models, and start mapping CPPs to critical quality attributes (CQAs). Glycosylation, charge variants, and DAR distribution become more than test results; they become process levers.

This is also where the first cracks in platform assumptions often appear. What worked at 10 L may not hold at 2,000 L. That’s not a failure, it’s an invitation to learn.

Phase 3 and commercial: validation and consistency

By Phase 3, the molecule is no longer a hypothesis, it’s a product. Controls must be locked, validated, and ready for regulatory scrutiny. We implement statistical process control, define alert/action limits, and ensure CPV systems are in place.

But here’s the catch: if we’ve under-invested in earlier phases, Phase 3 becomes a scramble. That’s why control strategies go beyond a compliance exercise; they help de-risk future steps.

From Platform Comfort To Process Precision: What We’ve Learned

For much of the last decade, the industry has leaned heavily on platform processes, especially for mAbs, to standardize upstream and downstream unit operations, reuse analytical methods, and accelerate early development. This approach enabled speed, reduced cost, and simplified tech transfer.

But as we’ve pushed into more complex modalities like ADCs, bispecifics, and engineered mAbs, the limits of platform thinking have become clear. These molecules don’t always behave like their predecessors. Their CQAs are more sensitive to subtle shifts in process conditions, and their safety and efficacy profiles are often tightly linked to attributes like glycosylation, DAR, or charge variants.

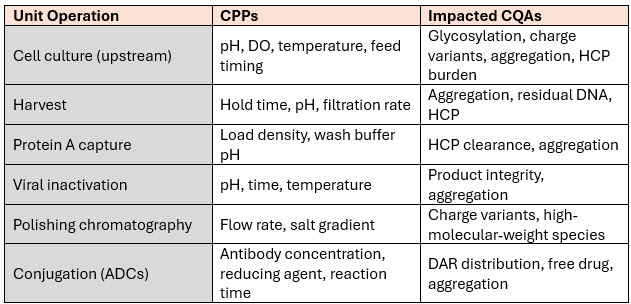

We now know that even within a platform, the mapping between CPPs and CQAs can vary significantly. For example:

This level of mapping is no longer a “nice to have” — it’s essential. It allows us to move from reactive control to predictive control, but it also requires investment in analytics, modeling, and cross-functional coordination.

And yet, even with this knowledge, we still see late-stage surprises. Why? Because control strategies, like any framework, are only as good as their execution.

When Control Strategy Meets Reality: Four Risks That Test The Strategy

Even the most well-structured control strategies can be blindsided by the realities of biologics manufacturing. These four real-world cases from published industry technical notes illustrate how early assumptions — often rooted in platform confidence or resource constraints — can obscure emerging risks. Each example reveals how a seemingly minor oversight in early development can cascade into major control, quality, or safety issues in later phases. More importantly, they show how control strategies can be strengthened to detect and mitigate these risks before they become program-threatening.

1. The hitchhiker HCP: when generic assays aren’t enough

Generic HCP enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) are a go-to tool in early development. They’re fast, broad-spectrum, and sufficient for initial safety assessments, but they can miss specific, co-purifying proteins that persist through downstream purification. In the case of lebrikizumab, PLBL2 — a lysosomal enzyme — was one such hitchhiker. It was enzymatically active, potentially immunogenic, and invisible to the generic assay.

Impact on control, quality, and safety:

- Persistent HCPs can degrade the drug product over time, compromising stability.

- Enzymatic activity may cleave or modify the therapeutic protein.

- Immunogenic HCPs can trigger patient immune responses, especially with chronic dosing.

- If undetected, these risks undermine the integrity of the control strategy and patient safety.

Why it is often missed early:

- Generic ELISAs are accepted practice in Phase 1, and their limitations are rarely challenged.

- Broad acceptance criteria and limited batch data make it easy to overlook subtle trends.

- The cost and complexity of proteomics or liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS)/MS are hard to justify early on.

What we learned and how to improve control strategies:

- Embed HCP trending into early-phase control strategies. Even if using generic ELISAs, trend total HCP levels across batches and flag outliers, even within broad acceptance criteria.

- Introduce orthogonal analytics in Phase 2. Incorporate LC-MS/MS or 2D electrophoresis to identify persistent or co-purifying HCPs. This enables earlier risk triage and links specific HCPs to upstream CPPs (e.g., DO, pH, lysis).

- Define HCP-specific CQAs by Phase 3. If a problematic HCP is identified, include it in the CQA panel and validate its clearance.

- Institutionalize HCP risk assessment. Build a decision tree into the control strategy that triggers deeper HCP characterization based on persistence, immunogenicity potential, or process correlation.

- If discovered late: Implement targeted polishing steps, develop specific assays, and proactively engage regulators with a risk-based mitigation plan.

2. The sugar shift: scale-up surprises in glycosylation

Glycosylation is one of the most scale-sensitive CQAs in biologics. In several biosimilar programs, afucosylation levels dropped significantly at commercial scale due to changes in mixing, gas transfer, and CO₂ removal. This altered antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), leading to failed biosimilarity and delayed approvals.

Impact on control, quality, and safety:

- Changes in glycosylation can affect potency, half-life, and immunogenicity.

- Inconsistent glycan profiles undermine comparability and regulatory confidence.

- For biosimilars, even small shifts can disqualify a product from being deemed “highly similar.”

Why it is often missed early:

- Platform scale-up rules are assumed to be sufficient, especially for mAbs.

- Lab-scale bioreactors don’t replicate the hydrodynamic and mass transfer conditions of 2,000 L-plus systems.

- Glycosylation variability is tolerated in early phases if bioactivity is acceptable.

What we learned and how to improve control strategies:

- Elevate scale-down model (SDM) development to a Phase 2 deliverable. Treat SDM qualification as a formal control strategy milestone, with defined acceptance criteria for mixing, gas transfer, and metabolite profiles.

- Map CPPs to glycosylation early. Use DoE to quantify how pH, DO, feed strategy, and temperature shifts affect glycan profiles.

- Integrate process analytical technology (PAT) tools. Consider inline Raman or mass spectrometry to monitor glycosylation precursors or surrogate markers in real time.

- Lock scale-sensitive CPPs in Phase 3. Validate that commercial-scale conditions maintain glycosylation consistency within clinically relevant ranges.

- If drift occurs late: Adjust operating parameters within validated ranges, enhance release testing, and prepare a comparability package with pharmacokinetics (PK)/ pharmacodynamics (PD) bridging data.

3. DAR heterogeneity: when upstream aggregation haunts ADCs

In brentuximab vedotin, upstream antibody aggregation led to high-DAR species during conjugation. Aggregated antibodies exposed more reactive thiols, resulting in over-conjugation. These high-DAR species were more hydrophobic, less stable, and potentially more toxic.

Impact on control, quality, and safety:

- High-DAR species increase aggregation risk and reduce shelf-life.

- They may alter pharmacokinetics and increase off-target toxicity.

- DAR heterogeneity complicates release testing and regulatory acceptance.

Why it is often missed early:

- Aggregation is often monitored post-purification, not post-harvest.

- Conjugation variability is tolerated in Phase 1 if safety is acceptable.

- The link between upstream harvest conditions and downstream DAR distribution is rarely explored early.

What we learned and how to improve control strategies:

- Treat aggregation as a Phase 1 sentinel metric. Use size-exclusion, high-performance liquid chromatography (SEC-HPLC) post-harvest to monitor trends, even if broad acceptance criteria are used.

- Correlate aggregation with conjugation outcomes in Phase 2. Use DoE to explore how pH, hold time, and temperature affect DAR distribution and free drug levels.

- Define aggregation-linked CQAs for ADCs. Include high-DAR species and free drug as release/stability criteria by Phase 3.

- Design conjugation robustness studies. Validate conjugation efficiency across a range of upstream aggregation levels to define safe operating space.

- If high-DAR species emerge late: Add polishing steps (e.g., HIC), segregate lots, and tighten release specs. Communicate comparability rationale clearly to regulators.

4. Glycosylation drift in EPO: potency lost in translation

Erythropoietin’s (EPO) therapeutic efficacy is tightly linked to its glycosylation profile — particularly sialylation, which governs serum half-life. During scale-up, subtle shifts in DO and nutrient availability reduced sialylation, shortening half-life and altering PK.

Impact on control, quality, and safety:

- Reduced sialylation leads to faster clearance and lower in vivo potency.

- Patients may require higher or more frequent dosing, affecting compliance and cost.

- Regulatory authorities may require bridging studies or dosing adjustments.

Why it is often missed early:

- Early-phase bioassays may not detect subtle PK differences.

- Glycosylation variability is tolerated if bioactivity remains within range.

- DO and nutrient gradients are hard to simulate without validated SDMs.

What we learned and how to improve control strategies:

- Quantify glycan profiles from the start. Use hydrophobic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) or matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) in Phase 1 to establish a baseline, even if variability is tolerated.

- Link glycosylation to functional assays. Correlate sialylation levels with in vitro potency or in vivo PK to define clinically relevant ranges.

- Use SDMs to simulate nutrients and oxygen gradients. Validate that scale-down models reflect commercial-scale DO and feed dynamics.

- Define glycosylation CQAs by Phase 2/3. Lock DO, feed composition, and timing to maintain glycan consistency.

- If drift is detected late: Enhance release testing, adjust dosing or labeling if needed, and prepare a bridging strategy with clinical justification.

These cases reinforce a critical truth: the most dangerous risks are often the ones that hide in plain sight. They’re not exotic, they’re familiar. They’re not due to negligence, they’re born from overconfidence in platform assumptions or underinvestment in early analytics.

When The Control Strategy Isn’t Enough: Acknowledging The Blind Spots

A resilient control strategy doesn’t just control known risks; it anticipates the unknowns, builds in early detection, and evolves with the molecule. Control strategies are necessary, but not sufficient. They can’t eliminate all risk. They can’t predict every scale-up surprise or analytical blind spot. And they can’t substitute for cross-functional vigilance.

Sometimes, the stumbling block isn’t technical, it’s organizational. Teams may defer to platform assumptions, delay investment in advanced analytics, or silo knowledge across functions. These are not failures of science, but of alignment.

We also need to acknowledge that control strategies can be weakened by overconfidence in early-phase data, underpowered scale-down models, or a lack of analytical sensitivity. In some cases, the tools exist, but the incentives to use them early don’t. That’s where leadership comes in, creating a culture that values early warning signs, funding exploratory analytics, and rewarding proactive risk mitigation.

Final Thoughts: Control Is A Verb, Not A Noun

If there’s one lesson I’d leave with fellow CMC and MSAT leaders, it’s this: control is not a static state, it’s a continuous act. A robust control strategy is not just a document; it’s a living system that adapts as the molecule, process, and organization evolve.

So yes, build your pyramid. Define your CPPs. Validate your models. But also ask: what might we be missing? Where are we over-relying on platform knowledge, and how can we design controls that not only pass inspection but withstand the unexpected?

Because in biologics, the unexpected isn’t the exception — it’s the rule, and the best control strategy is one that’s ready to learn.

About The Author:

Victor Lien, Ph.D., is a CMC strategy and platform developer with extensive experience across several advanced modalities, including antibody-drug conjugates, cell and gene therapies, and mRNA. He most recently worked as a director of biotherapeutic pharmaceutical sciences at Pfizer. Before that, he was a director of CMC and tech transfer at Gracell Biotechnologies, now a part of AstraZeneca. Other experience includes leadership positions at Bristol Myers Squibb, DowDuPont, Fluidigm, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals. He was also a systems biology instructor at Harvard Medical School. He received his Ph.D. from the University of California San Diego.

Victor Lien, Ph.D., is a CMC strategy and platform developer with extensive experience across several advanced modalities, including antibody-drug conjugates, cell and gene therapies, and mRNA. He most recently worked as a director of biotherapeutic pharmaceutical sciences at Pfizer. Before that, he was a director of CMC and tech transfer at Gracell Biotechnologies, now a part of AstraZeneca. Other experience includes leadership positions at Bristol Myers Squibb, DowDuPont, Fluidigm, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals. He was also a systems biology instructor at Harvard Medical School. He received his Ph.D. from the University of California San Diego.