Meet Mus silicium

To get scientists to think deductively, two researchers are offering cash prizes for solving a neural network

John Hopfield wants to keep neuroscientists from falling into the trap of becoming data mongers—like their genomics counterparts—to the exclusion of using deductive reasoning, and he's organizing a competition to do it. Hopfield, of Princeton University (Princeton, NJ), and his colleague neurobiologist Carlos Brody from New York University, are challenging scientists to determine the inner workings of a virtual mouse they created called Mus silicium (sand mouse). This mouse, which can be viewed on the Mus silicium website, has the unusual property (unusual for a mouse anyway) of recognizing the spoken word "one" and the challenge is to figure out how he does this.

John Hopfield wants to keep neuroscientists from falling into the trap of becoming data mongers—like their genomics counterparts—to the exclusion of using deductive reasoning, and he's organizing a competition to do it. Hopfield, of Princeton University (Princeton, NJ), and his colleague neurobiologist Carlos Brody from New York University, are challenging scientists to determine the inner workings of a virtual mouse they created called Mus silicium (sand mouse). This mouse, which can be viewed on the Mus silicium website, has the unusual property (unusual for a mouse anyway) of recognizing the spoken word "one" and the challenge is to figure out how he does this.

This rodent is actually a computer simulation of a network of 660 brain-cell-like components. Hopfield and Brody are offering a cash prize to anyone who can determine the inner workings of this mouse. Figuring it out elucidates some powerful new principles "that [tell] how you can put particular algorithms into particular hardware," said Hopfield.

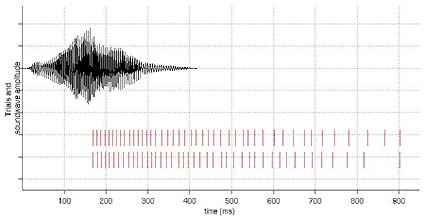

The Mus silicium challenge consists of two parts. The first is to write an essay explaining how to deduce the neural network that produced the experimental data published at the website http://shadrach.cns.nyu.edu/~carlos/Organism/index.html.

The other is to create a neural network of similar scale and complexity to Mus silicium that can perform the same task. Hopfield compared the question posed to: "given a certain number of transistors, capacitors, and resistors, how well can you solve this signal processing problem?" Solutions can be sent to either hopfield@princeton.edu or carlos@cns.nyu.edu before December 1, 2000.

Participants wanting additional data to help them solve either question can experiment on the Mus. A sound file of voices saying "one" or other things, such as sine waves of different frequencies, can be uploaded to the Mus silicium homepage, where it will be tried out on the mouse and the output posted. A few hundred such experiments have already been carried out.

First prize for each contest, as judged by Hopfield and Brody, is $500 and a Handspring Visor personal digital assistant. Second prize is $200 and a Visor. Jeff Hawkins, founder and chairman Handspring Inc., is footing the bill for the contest. Hawkins is a neural systems buff, and sponsored a seminar last month in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, at which Hopfield and Brody first announced their challenge.

Hopfield chose to publish the Mus silicium principles as a challenge rather than a traditional technical paper because he felt there is not enough emphasis in neuroscience on deductive reasoning. Faced with incomplete knowledge of a system, neuroscientists tend to seek the answer to a problem by gathering more data rather than by trying to deduce the system's workings from what they already know. With the increasing use of high-throughput discovery techniques in the life sciences, the temptation to keep collecting data has only become stronger. But Hopfield guarantees that Mus silicium can be solved just from the data at the website.

The two scientists will post the solution and the names of the winners at the Mus silicium website on 14 December. On the same day Hopfield will deliver a talk on the principle at Princeton. Hopfield expects to publish the answer to the Mus silicium riddle and the principles it illustrates later in Proceedings of the National Academy of Science USA.

For more information, visit the Mus silicium website at http://shadrach.cns.nyu.edu/~carlos/Organism/index.html.

By Laura DeFrancesco

Managing Editor, Bioresearch Online

Email: ldefrancesco@bioresearchonline.com