mAbs For Migraines: Crowded Field A Headache For Drug Developers

By Angela Sparrow, Ph.D., Decision Resources Group (DRG)

Migraine is a highly prevalent disease, with more than 30 million “migraineurs” living in the United States alone. Migraine comprises two main populations: episodic migraine (EM; patients suffering less than 15 headache days per month) and chronic migraine (CM; patients suffering 15 or more headache days per month, with at least eight having migraneous features). Over the past 25 years, since the birth of the “triptans” (e.g., sumatriptan [GSK’s Imitrex]), most pharma industry focus in migraine has been on acute treatment — drugs taken at the onset of a migraine to stop the pain. There are now seven triptan molecules in nine formulations (with three more in development) and several NMEs for acute treatment advancing through the pipeline.

By comparison, chronic prevention has been underemphasized clinically and neglected by pharma. Until recently, drug “discovery” was lacking in this space; treatment options — e.g., antiepileptic drugs, beta blockers, and antidepressants — are borrowed from other diseases that were serendipitously found to alleviate migraine pain. Over time, this has forged a mix of on- and off-label standards of care (SoC) that deliver suboptimal efficacy and a host of unwanted side effects, constraining prophylactic treatment rates and patient compliance. Until 2018, the last big clinical/commercial event in migraine prevention came with the approval of Allergan’s Botox for CM in 2010. Though efficacy results were only marginally better than daily oral therapies, Botox was well tolerated, with few side effects, and targeted the most underserved migraineurs, thereby amassing substantial patient interest. Even still, Botox is not for everyone, and payer restrictions relegate Botox to third-line or later treatment and EM patients, especially those with high-frequency EM (nine to 14 headache days per month), are excluded from treatment. For millions of migraineurs, alternatives are sorely needed.

Enter CGRP

For years, developers have tried to advance drugs targeting the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) system, a novel pathway with direct ties to the migraine pathology. Several oral CGRP antagonists for acute and preventive treatment were advancing through the pipeline earlier in the 2000s, but development ceased when liver toxicity issues surfaced during late-phase trials for Merck’s potentially first-in-class candidate telcagepant; the discovery eventually shuttered similar programs from several other developers.

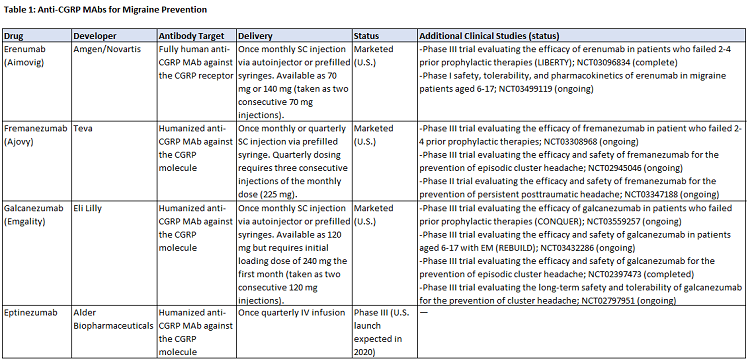

Since that time, there has been a resurgence in this arena, with the development of four anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) for EM and CM prevention: Amgen and Novartis’s Aimovig (erenumab), Teva’s Ajovy (fremanezumab), Eli Lilly’s Emgality (galcanezumab), all of which launched in the U.S. market in 2018, and Alder BioPharmaceuticals’ eptinezumab, currently in Phase 3 development. Four small molecule CGRP antagonists are also in development for acute and/or prophylactic treatment. Though not a cure for migraine, the efficacy of the mAbs is better than many of today’s SoCs, with some patients achieving a ≥75 percent reduction in monthly migraine days. Unlike the prior oral antagonists, the anti-CGRP mAbs have not been associated with any concerning safety signals; however, regulators and physicians will pay close attention to their safety over the long term as post-market experience accumulates.

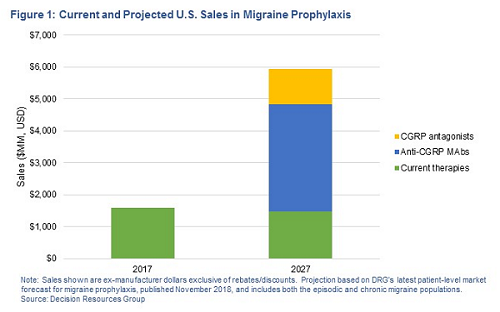

Data from recent surveys of migraine-treating U.S. neurologists, conducted by Decision Resources Group (DRG), indicates that initial uptake of Aimovig, Ajovy, and Emgality has been solid and is expected to grow meaningfully. That said, at $6,900 per year, these drugs are not cheap and payers will do what they can to contain costs in a potentially huge, underserved population desperate for alternatives. Assuming even modest overall uptake, U.S. ex-manufacturer sales of the four anti-CGRP mAbs could eclipse $3 billion, and combined with new antagonists, CGRP-targeted therapies could grow the prophylactic market by more than $4 billion by 2027 — figures that highlight the untapped commercial opportunity in the chronic prevention segment propelling the current CGRP wave. For developers in an ever-crowding market, the key now is differentiation.

The Choice Is (Un)Clear

Compared with most SoCs, the anti-CGRP mAbs stand apart as being developed specifically for migraine, well-tolerated with improved (but not overwhelming) efficacy, and infrequently dosed. But compared with each other, they are more similar than different. With three mAbs having launched within a six-month period and a fourth yet to come, many questions remain about how physicians will choose between them and which among them may ultimately win out.

Delivery

More than half of U.S. neurologists (n = 100) surveyed by DRG in July 2017 indicated that delivery would not be a factor in CM patients’ preference or willingness to try a new prophylactic treatment with proven efficacy. However, given that the efficacy of the mAbs is largely comparable, delivery invariably becomes a differentiating feature. Table 1 shows the administration profiles for the four mAbs; differences center on strengths offered, dosing frequency, formulations, and the availability of autoinjectors. In a November 2018 survey, U.S. neurologists (n = 75) overwhelmingly rated the availability of an autoinjector as valuable, but less than one-quarter indicated the lack of an autoinjector as a disadvantage — thus, while the convenience of an autoinjector has patient-centered value, its absence may not hinder prescribing. In regard to dosing schedule, approximately half of surveyed neurologists indicated a monthly-only option as a disadvantage. Quarterly dosing allows more freedom and control, an option that some patients are gravitating toward: In its Q3 2018 earnings call, Teva estimated approximately 20 percent of Ajovy prescriptions had been for quarterly dosing. Finally, for later-to-market eptinezumab, IV administration may further differentiate it, providing an alternative to SC injections and possibly supporting a role in hospital emergency rooms.

Efficacy

Efficacy on core endpoints is largely similar between mAbs, though some migraine experts believe eptinezumab is the most effective; clinical trial data suggests the drug is effective within the first 24 to 48 hours, an advantage for patients who experience near daily migraines, and a portion of patients in the study experienced a 75 percent or 100 percent reduction in migraines. Developers are using additional clinical studies to differentiate the efficacy profiles of their products. Data shows Aimovig and Ajovy are effective in patients who failed two or more prophylactic agents, an attribute seen as highly valuable by surveyed neurologists; a similar trial is ongoing for Emgality. Amgen and Lilly are sponsoring trials in pediatric and adolescent patients, which could expand the patient pool into new segments. Finally, mAbs are being investigated in other headache types — Ajovy is in a Phase 2 trial for post-traumatic headache and both Emgality and Ajovy are in Phase 3 trials for episodic cluster headache (for which Emgality received FDA breakthrough designation), a vastly underserved market with no approved preventives.

Antibody Target

Aimovig is the only anti-CGRP mAb targeting the CGRP receptor; the others target the CGRP molecule. Aimovig is also the only fully human antibody, while the others are humanized. At this time, it is unclear if either will lead to long-term efficacy or safety advantages. In November 2018, the majority of neurologists (n=43/75) agreed they would likely try a patient on a second anti-CGRP mAb in the event of failure, but less likely to try a patient on a third mAb. This could yield a potential advantage for Aimovig — either as the “first-line” mAb or as the natural next step if a patient first fails a competing mAb.

Affordability And Access

Novartis/Amgen, Teva, and Lilly each offer some type of patient access program to get patients started on their products. These access programs include free trial programs (some limited only to patients with commercial insurance), bridging programs for patients who are denied insurance coverage, and reduced copay programs. However, when these offers expire, the success of payer negotiations will be of utmost importance; more than two-thirds of surveyed neurologists agree their choice of anti-CGRP mAb will largely depend on insurance coverage and will prescribe the drug that is most readily available to their patients. Moreover, heavy restrictions or high cost sharing for patients will be detrimental: More than half of neurologists (n=100) surveyed by DRG in August 2018 indicated they would not prescribe/would be much less likely to prescribe an anti-CGRP MAb if out-of-pocket costs to patients or restrictions were too burdensome.

Where To Go From Here?

The dynamics in the anti-CGRP space are somewhat unique, with three high-cost brands in the same novel drug class approved within a six-month period and entering a highly generic market. That said, tight competition and the need for differentiation is central in any number of disparate pharmaceutical markets. In the tight race between the anti-CCRP mAbs, HEOR (health economics and outcomes research) strategies, tactical commercialization, and educational outreach targeted directly at payers, providers, and patients could pay dividends; the following recommendations could also apply, specifically or generally, to other current and future competitive environments.

Payers will be selective about which, and how many, mAbs they include on formulary and will leverage competition to lower costs. In a blow to Teva, Express Scripts, one on the largest PBMs in the United States, made the decision to cover only Aimovig and Emgality, excluding Ajovy from its 2019 National Preferred Formulary. The move makes clear that to win with insurers, companies must be prepared for aggressive rebating and/or employ other tactics, such as offering risk-based contracts that tie coverage to real-world performance and strengthening cost-effectiveness justifications (e.g., Phase 4 studies showing an effect on hospitalizations, total acute drug use, comorbidities, and/or patient compliance relative to SoCs). For pipeline candidates (e.g., eptinezumab, CGRP antagonists), competitive pricing relative to Aimovig, Emgality, and Ajovy will undoubtedly be a persuasive lever.

Especially during this fiercely competitive rollout period, in which three drugs are vying for pent-up demand, the key is getting patients on treatment. This is being accomplished in part through sampling and the aforementioned free-trial/bridge programs while payers finalize their coverage decisions. A majority of surveyed neurologists see it as a disadvantage if companies fail to offer coverage for patients when insurance is denied. Companies could consider expanding these programs to include non-commercially insured patients, which neurologists indicate cover a healthy proportion of their patients. Amgen and Novartis offer a two-month free trial to all patients; however, after that trial has ended, patients without commercial insurance do not qualify for additional patient assistance programs.

Companies should sponsor physician continuing medical education (CME) programs. The anti-CGRP mAbs are new in many ways — the first in an entirely new class of drugs and the first mAbs approved for pain — and neurologists understandably cite lack of familiarity as an obstacle to prescribing. Surveyed neurologists and interviewed KOLs request informational programs for physicians who are unfamiliar with these new treatments or need a refresher in migraine and headache medicine. Developers can take a page from Allergan’s playbook early this decade in support of Botox to review the clinical data, drive increased awareness of the poorly recognized CM population, and train physicians on its administration. From the patient perspective, survey data shows that neurologists will take patient requests for specific migraine drugs into consideration when prescribing new treatments. Developers can support demand through effective media marketing and headache awareness campaigns to the migraine community through print, media, and online channels that reinforce a message of a newfound hope to treatment-refractory migraineurs. Convenient mobile tools reminding patients to take their monthly medication or help track headache frequency (e.g., a migraine diary app) also may appeal — and not only to patients, but also to payers. Together, these activities could go a long way in the battle for brand visibility and share of voice.

Last, despite the legitimate progress they represent, the anti-CGRP mAbs are far from a cure, nor will they be effective in all patients. Opportunity for alternatives invariably remains. The prevention market will soon be saturated with biologic and small molecule CGRP-targeted therapies, boasting excellent tolerability, likely strong safety, and various delivery options. Assuming significant new efficacy gains in this class are unlikely, drug developers observing the unfolding dynamics within the CGRP class and tempted by a prophylaxis renaissance in migraine should give serious consideration to moving in a new direction and identifying the next new crop of migraine prevention therapies. Already, developers are beginning to turn their attention to new targets, such as PACAP-38, a target for which Amgen/Novartis and Alder have early-stage candidates. Ultimately, the initial demand for CGRP therapies speaks to the undeniable market potential for new safe and effective preventive treatments. Hopefully, we find ourselves standing merely at the doorstep to a new world of drug choice and therapeutic benefit for millions of underserved migraineurs.

About The Author:

Angela Sparrow, Ph.D., covers the pain and psychiatry space as a principal analyst in the CNS and Ophthalmology team at DRG. She provides expert insight and authors primary market research and forecasting content with a focus on migraine and opioid addiction. Previously, Sparrow was a postdoctoral fellow at McLean Hospital, Harvard Medical School, studying the role of kappa opioid receptors in addiction and withdrawal-induced depression. She holds a Ph.D. in behavioral neuroscience from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a bachelor’s degree from Northeastern University. You can reach her at asparrow@teamdrg.com or connect with her on LinkedIn.

Angela Sparrow, Ph.D., covers the pain and psychiatry space as a principal analyst in the CNS and Ophthalmology team at DRG. She provides expert insight and authors primary market research and forecasting content with a focus on migraine and opioid addiction. Previously, Sparrow was a postdoctoral fellow at McLean Hospital, Harvard Medical School, studying the role of kappa opioid receptors in addiction and withdrawal-induced depression. She holds a Ph.D. in behavioral neuroscience from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a bachelor’s degree from Northeastern University. You can reach her at asparrow@teamdrg.com or connect with her on LinkedIn.