Is Biopharmaceutical Industry At Risk Of Getting Vasa Syndrome?

Alain Pralong, CEO, Pharma-Consulting ENABLE GmbH

Abstract

The biopharmaceutical industry exhibits significant granularity with regard to the maturity level of product development and maintenance. Part of this granularity is the result of the history of the biopharmaceutical industry starting 220 years ago with vaccines at the end of the 18th century, followed by Penicillin manufacturing in the 1940s, the development of monoclonal antibodies in the 1970s, and T-cell therapies in early 2000s, respectively. Over this long time period, general knowledge and scientific understanding has massively progressed in sync with the development of analytical methods and tools what until today significantly modulated the maturity level of product development and maintenance from a scientific point of view.

As the biopharmaceutical industry is not only science-driven, the interesting question to ask is how company culture and ways-of-management impact the maturity level and the granularity in a positive or negative way. In general, the current behavior of the biopharmaceutical industry is seen as extremely risk adverse and very keen on generating revenue, while being exposed to continuously increasing expectations from regulatory authorities. The stress field of this antagonism can prime company culture and ways-of-management into a direction neglecting continuous science-based product development and maintenance for short-time risk-management and revenue, which in the end translates and materializes in significant risk exposure.

Interestingly, similar managerial driving forces have led to the loss of the mighty Vasa on her maiden voyage in the harbor of Stockholm in 1628, prompting questions on parallels and lessons-to-retain in today’s context.

Introduction

The biopharmaceutical industry is one of the most successful and revenue generating industries existing today. Its history shows a massive evolution over time that has been massively accelerated with the advent of recombinant DNA technology, the advances in analytical methodologies, and the progress of understanding medical disease in the second half of the 20th century. Start up companies then pursuing these promises have grown into established, large, and mature organizations such as Amgen, Biogen, GSK, Sanofi, Merck, and Genentech based on the success of the novel classes of drugs they developed. The so-called blockbuster era they initiated has permitted them to completely change the market repartition between small molecules and biopharmaceuticals.

The growth associated with these successes has primed a whole sequence of changes within the biopharmaceutical industry ranging from market consolidation through M&A, loss of initial inventor start up spirit, replacement of innovation by risk adverseness, loss of balanced risk assessment & management, and adopting a business acumen focusing on short-term revenue, respectively.

The specific hallmarks of biopharmaceuticals today however, warrant the question if general management principles are sufficient / adequate for an industry developing products over long cycle times and with subsequent massive needs over decades as was the case for vaccines, for example.

Several key indicators for the biopharmaceutical industry, such as decreasing success rates in new product development (1), increasing cost of new product development (2), increasing number of regulatory enforcement actions (3,4,5), and 2-3 sigma level process robustness producing the associated scrap during manufacturing (6,7), present a different picture from that of the one conveyed by the sales and revenue of the blockbuster drugs. Furthermore, established biopharmaceutical companies have developed growth models based on the acquisition of start-up companies with interesting and promising products and/or technologies. Unfortunately, a significant number of the big biopharmaceutical companies have had problems providing the appropriate environment to help build these promises.

Today, the materializing patent cliff of blockbuster drugs, the weakness of internal pipelines after depletion of the obvious targets, the increasing compliance risk with evolving regulatory requirements, and the increasing competition of generics manufacturers in the emerging and developing world are all exerting pressure on the biopharmaceutical industry, particularly in the developed world. This broad and high-level assessment of the current state of biopharmaceutical industry raises the question of how the biopharmaceutical industry in the developed world shall adapt to the numerous pressures to remain scientifically and economically competitive in the future. Hence, the time might be right to explore what drivers and factors led to this situation and how other industries have attempted and achieved a turn-around.

Management Style And Company Culture

Having worked in several small, medium, and large biopharmaceutical companies, I experienced various management styles and company cultures. Normally, in a highly educated environment such as our industry, our main focus is on resolving issues. Despite this general genotype, the efficiency and the successes I witnessed varied significantly depending on the applied management style and resulting company culture. The two major management styles I witnessed were either the consensual approach or the autocratic management style. My experience with both management styles and resulting company cultures is that they do neither foster nor ensure success. As Brian J. Robertson has well described, the consensual management style results in few decisions being made and more time being spent in meetings rather that getting the work done (8). The effort and time required to find a decision is so high that the system gets bypassed more often than not. Hence, consensus-based organizations often have the same issues as organizations with no explicit structure (8,9). On the other hand, the autocratic management style pursing a top-down predict-and-control approach is disempowering the entire organization, which, in the end, prevents getting work done (8,10). Decisions in that environment are taken to an Olympian peak far away from frontline realities and require enormous, inefficient bureaucratic structures for internal communication up and down the hierarchic chain (8,9).

Furthermore, witnessing both extremes, I experienced that they encourage personnel and leaders to reject responsibility and accountability. In the consensual management environment, responsibilities and accountabilities are diluted such that the main objective becomes keeping the consensus alive rather than the execution and delivery of key actions. In the autocratic environment, personnel and leaders push responsibilities and accountabilities back in order to avoid reprimand should any issues and failures arise. Therefore, both management approaches result in a major slow down of all activities and a wide spread risk adverseness to prevent exposure of individuals. With other words, the extremes are definitively not providing a fertile ground for addressing the current challenges but are probably one of the main reasons that led to today’s issues.

Vasa Syndrome

The disaster of the mighty Vasa sinking in 1628 on her maiden voyage in the harbor of Stockholm is an interesting case study for assessing the factors endangering a complex, lengthy, and very costly endeavor such as building the largest battle ship the world has seen until then. Figure 1 shows the preserved Vasa which had been recovered from Stockholm harbor in 1959 – 1961.

Figure 1 shows the restored Vasa in her dry dock in Stockholm, Sweden.

Considering the fate of the Vasa as a 17th century production disaster, analysis on the prevailing management style and culture performed by Eric H. Kessler of Stanford University led to the creation of a list of managerial errors leading to this disaster (11). Today, Vasa syndrome refers in both management and marketing circles to problems in communication, goal setting, adaptability, and management affecting projects, sometimes causing them to fail. The sinking of the Vasa has also been used as an example for business managers on how to learn from previous mistakes (11,12). Table 1 outlines the seven factors driving the Vasa disaster.

|

No |

Description |

Situation – Do and Don’ts |

|

1 |

Lack of external learning capacity |

Leaders in the old technology have tangible and intangible resources invested to the extent that it is difficult for them to abandon historical areas of strength |

|

2 |

Goal confusion |

Do not tinker with product design in an attempt to please all internal groups |

|

3 |

Obsession with speed |

Use fast-paced development as a means, not as an end. Do not compromise the integrity of a product in the interest of blindly speeding it to market |

|

4 |

Feedback system failure |

Don’t rationalize away bad news in the process of finding solutions to problems |

|

5 |

Communication barriers |

Organizations must promote the sharing and integration of knowledge within and across project teams and develop a system that creates a culture with a positive attitude towards reconciling divergent viewpoints |

|

6 |

Poor organizational memory |

During the new-product development process, tacit knowledge must be converted into explicit knowledge that can be understood by individuals lacking experience in a specific area |

|

7 |

Top-management meddling |

Organizations need to staff projects with good people and let them do their jobs |

Table 1 lists the seven management factors identified by Eric H. Kessler that have led in the end to the sinking of the Vasa.

These factors make it obvious that to develop, materialize, and deploy their negative impact, a specific management environment and company culture are needed.

Is The Biopharmaceutical Industry At Risk Of Getting Vasa Syndrome?

Scientific and technological progress has permitted a significant evolution of scientific knowledge and understanding leading to and supporting development of the modern biopharmaceutical industry we know today. Many big multi-nationals generating multi-billion US$ revenues every year, started as small start-up companies only three decades ago. While the success of biopharmaceutical drugs has primed and permitted the building of a new industry, it is obvious that the speed of this massive growth and the economic market expectations it fosters has hampered and maybe even prevented in certain sectors the development of the maturity level required for reliable and sustainable drug manufacturing.

Recurrent issues with process robustness, quality of raw materials, feasibility of analytical methods, and compliance with evolving GMP regulations, respectively, are just displaying some of the weaknesses of today’s biopharmaceutical industry (3,4,5). The origins can certainly be associated with the industry’s rapid growth, but other factors must have strongly prevented evolution and adaptation to the required level as well. This is intriguing given the increasing experience the biopharmaceutical industry has gathered over the last 30 years in developing and manufacturing drugs. This accumulation of experience should have normally condensed into increasing maturity, robustness, and sustainability. However, an increasing number of regulatory enforcement actions, product stock outs, and supply constraints point in the opposite direction and could be viewed as the beginning of a biopharmaceutical production disaster (11).

Other factors seem to be preventing the biopharmaceutical industry from reacting to these troublesome indicators, which could be the consequence of the preexisting managerial environment and company culture. Until today, the biopharmaceutical industry has neither questioned nor reviewed its mode of operation and seems to be locked in the established ways of working. The success might have primed Warren Buffet’s ABC of business decay (Arrogance, Bureaucracy, and Complacency), allowing the inefficient managerial approaches described earlier to continue what could obviously put at risk the success of the concerned biopharmaceutical companies (13,14). The resulting company culture on the other hand establishes isolation from the outside world and keeps external influences at bay.

In that sense, the challenges the biopharmaceutical industry is facing today in the developed world are very similar to the ones encountered during the construction of the Vasa 400 years ago. Hence, we are effectively at risk of acquiring the Vasa syndrome.

Can A New Management Approach Bring The Solution Paired With A New Company Culture?

Crisis situations inspire difficult decisions and actions. Often, crisis management is employed to drive a so-called turnaround leading to a complete reorganization of the company, as well as a significant reduction of personnel. While this activism provides a good feeling of getting finally momentum and even more so in organizations having been stable for a prolonged period of time, it fails to profoundly change the management style and the company culture. Unfortunately, experience shows that this approach results in complete paralysis after a very short time period, as it only replaces the consensual or autocratic management style with another autocratic management style even more disconnected from the frontline realities by focusing on realizing the forecasted synergies and savings (8). Hence, this wide-spread approach increases insecurity and eliminates focus without fostering responsibility and accountability of the remaining personnel. The end result is that even less work is getting done and that further reorganizations are required to eventually find a new basis permitting rebuilding of an efficient and functional framework producing valuable output.

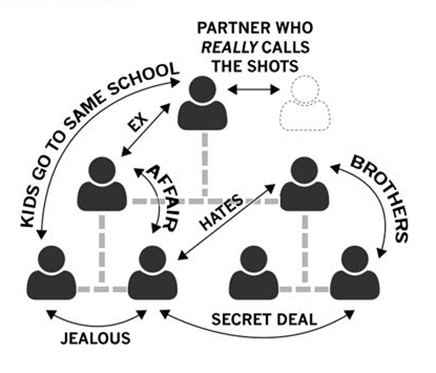

Given the fact that neither consensual nor autocratic management styles produce the desired results opens the possibility to assess other management styles. As Brian J. Robertson describes, one of these is to empower others by positioning the leader in a “good parent” role (8,9). As he points out, this approach paradoxically transforms the empowered employee into a victim as the organizational structure is still fundamentally disempowering given the fact that the ultimate reliance remains with the autocratic leader (9). Furthermore, the traditional hierarchical setup is prone to many influences that have nothing to do with the mission of the company but can significantly hinder and complicate adaptation and evolution to make sure work is being done for the good of the company as shown in Figure 2 (8,15).

Figure 2 shows how other factors can heavily impact the functioning of traditional management structures.

Hence, radically new management approaches are required to adapt to a continuously evolving environment that requires activation of all employees in sensing risks, opportunities, and trends to ensure work is getting done.

Holacracy, developed by Brian J. Robertson, offers a promising alternative to the biopharmaceutical industry as it permits shifting from personal leadership embedded in a governance structure to constitutionally derived power to govern and operate an organization defined by a set of core rules which are distinctly different from a traditionally managed organization (8). The elements characterizing and distinguishing Holacracy are a constitution that sets the rules and redistributes authority, a new way to structure an organization and define people’s roles and spheres of authority within it, a decision making process for updating those roles and authorities, and a meeting process for keeping teams in sync and getting work done, respectively (8). These hallmarks permit the creation and embedding of a complete system for self-organization. Power is removed from the management hierarchy to clear roles, which can be executed autonomously, without a micromanaging boss (8). This enables structuring work even better than in a conventional setup as there are clear rules and processes guiding teams on how to break work and define roles, responsibilities and expectations (8). Table 2 compares the hallmarks of the traditional management approach with Holacracy.

|

In Traditional Companies |

With Holacracy |

|

Job descriptions |

Roles |

|

Each person has exactly one job. Job descriptions are imprecise, rarely updated, and often irrelevant |

Roles are defined around the work and are updated regularly. People fill several roles |

|

Delegated authority |

Distributed authority |

|

Managers loosely delegate authority. Ultimately, their decision trumps alternative options |

Authority is distributed to teams and roles. Decisions are made locally |

|

Big re-organizations |

Rapid iterations |

|

The organization structure is rarely revisited, mandated from the top |

The organizational structure is regularly updated via small iterations. Every team self-organizes |

|

Office politics |

Transparent rules |

|

Implicit rules slow down change and favor people “in the know” |

Everyone is bound by the same rules, CEO included. Rules are visible to all |

Table 2 compares the hallmarks of traditional management structures and Holacracy. Adapted from (16).

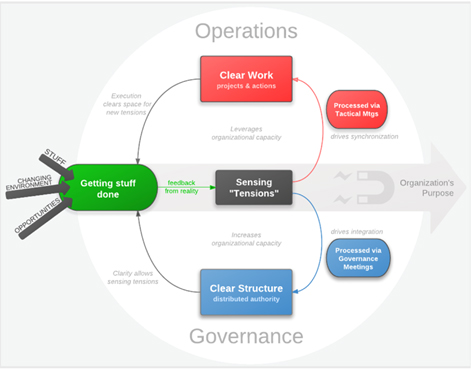

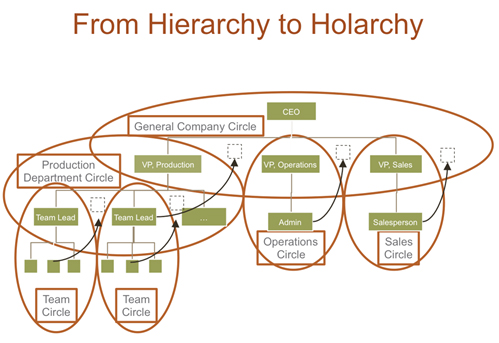

Once embedded, the power of Holacracy resides in its ability to continuously sense tensions while getting work done exposed to the frontline realities (8). Teams known as circles can continuously react to tensions building on the rules and processes set in the constitution by either consulting on Operations to clarify work or on Governance to clarify structure (8). The main driving force for the circles is however the mission of the company, which can be for a vaccine manufacturer for example ensuring reliable supply of x vaccine doses per year. Figure 3 illustrates the working principle of a circle with distributed authority (15). Hence, when introducing Holacracy, a traditional hierarchy has to be translated into a structure of circles each outfitted with distributed authority (8). Figure 4 shows a nice overlay of a hierarchic and a holacratic organizational structure (15).

Figure 3 shows the organization of a circle within Holacracy. It becomes directly visible how this management approach permits to sense and adapt to output of sensor dealing with the frontline realities.

Figure 4 shows an overlay between the traditional management structure and the application of Holacracy creating different circles each having distributed authority.

It is absolutely clear that shifting to Holacracy would be a dramatic change in today’s biopharmaceutical industry. The types of recurrent and increasing problems we are facing however, exerts such pressure for improvement that only accepting the failure of established ways of working will allow adaptation and evolution of the entire industry towards a reliable supply of existing and new drugs at the expected scientific and regulatory compliance and economic competitiveness. This level can only be achieved and maintained if all contributors are activated and can act as sensors within their frontline realities and have the authority to fully support and contribute to the mission of the biopharmaceutical company.

Some might claim that the biopharmaceutical industry operates within a highly regulated environment that does not permit change, and, therefore, we have to stick to an autocratic management style to ensure compliance. In my eyes, it is just this dogma that leads to non-compliance and subsequent regulatory enforcement actions. The initiatives of various regulatory authorities for embedding GMPs of the 21st century clearly indicate that they have recognized stagnation as a threat. This is supported by Janet Woodcock’s quotes at ISPE 2013 (17). Woodcock stated:

The mantra that we had through the 21st century was that our goal would be a pharmaceutical manufacturing sector that could reliably reproduce high quality drug products with minimal regulatory oversight. In other words, it was quality driven and I don’t think we’re there yet…One of the things that we acknowledged when we started the 21st industry initiative was that intense regulation was holding back industry’s ability to continuously improve and innovate. That’s because of the intense regulatory strutting over any changes, and the timeframe required to get regulatory clearance for any kind of changes. So we need to provide industry more freedom to operate in return for when they have achieved a quality production.

The biopharmaceutical industry has arrived at a critical point where the operating models that have built this industry are not adapted to ensure its future. New, holistic, open, and bold thinking is required to spark the momentum that will break new ground for the biopharmaceutical industry to overcome its current challenges.

References

- Pammolli F, Magazzini L, Riccaboni M. : The productivity crisis in pharmaceutical R&D. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011 Jun;10(6):428-38.

- Efpia: The Pharmceutical Industry in Figures – key data 2014. (internet) Available from: http://www.efpia.eu/uploads/Modules/Mediaroom/figures-2014-final.pdf (cited July 28th 2015)

- FDA Warning Letters archive (internet) Available from: http://www.fda.gov/ICECI/EnforcementActions/WarningLetters/default.htm (cited July 28th 2015)

- FDA Enforcement Actions archive (internet) Available from: http://www.fda.gov/ICECI/EnforcementActions/EnforcementStory/EnforcementStoryArchive/default.htm (cited July 28th 2015)

- FDA Enforcement Activity (internet) Available from: http://www.fda.gov/ICECI/EnforcementActions/ucm247813.htm (cited July 28th 2015)

- IBM Business Consulting Services: The metamorphosis of manufacturing (internet) Available from: http://www.pharmamanufacturing.com/assets/Media/MediaManager/ibmbizconsult_metamorphosisofmfg.pdf (cited July 28th 2015)

- Nasr M.M., Winkle H.N. : FDA Perspectives: Understanding Challenges to Quality by Design (internet) Available from: http://www.pharmtech.com/fda-perspectives-understanding-challenges-quality-design (cited July 28th 2015)

- Robertson B.J. : Holacracy – The new management system for a rapidly changing world (2015) ISBN 978-1-62779-428-2

- Hamel G. : First, let’s fire all the managers (2011) Harvard Business Review (internet) Available from: https://hbr.org/2011/12/first-lets-fire-all-the-managers (cited August 2nd 2015)

- Allen D. : Getting Things Done - the art of stress-free productivity (2001,2015) ISBN: 9780857979728

- Kessler E.H., Bierly P-E, and Gopalakrishnan S. : Vasa Syndrome: Insights from a 17th-Century New-Product Disaster The Academy of Management Executive (1993-2005) Vol. 15, No. 3, Themes: Insights from Sports, Disasters, and Innovation (Aug., 2001), pp. 80-91

- The Vasa Syndrome (internet) Available from: http://www.innergy.co.uk/forum/?p=601 (cited July29th 2015)

- Buffett Says Next Berkshire CEO Must Fight Arrogance, Decay (internet) Available from: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-02-28/buffett-says-next-ceo-must-fight-decay-complacency-at-berkshire (cited July 29th 2015)

- Gilbert M. : Warren Buffett’s ABC of business failure (internet) Available from: https://www.pressandjournal.co.uk/fp/business/north-of-scotland/513986/martin-gilbert-warren-buffetts-abc-business-failure/ (cited July 29th 2015)

- Platts C. : Holacracy – what is it exactly (internet) Available from: http://blog.talentrocket.co.uk/holacracy-what-is-it-exactly/ (cited August 1st 2015)

- Holacracy – How it works (internet) Available from: http://www.holacracy.org/how-it-works/ (cited August 1st 2015)

- Woodcock J. ISPE 2013 (internet) Available from: http://qbdworks.com/dr-janet-woodcock-cder-fda-ispe2013/ (cited August 2nd 2015)