How To Establish Growth Promotion Tests For Pharmaceutical Culture Media

By Crystal M. Booth, PSC Biotech

Growth promotion testing of culture media appears to be a trivial test, but this perception is deceiving. Almost everyone can agree that with the criticality of microbiological tests, it is extremely important that culture media performs properly. Culture media is used in most assays in a microbiology laboratory, and if the media does not properly support growth, false negative results may be obtained. Likewise, contaminated media may yield false positive results. Opinions on when and how the testing should be performed sometimes vary within the pharmaceutical industry.

Growth promotion testing of culture media appears to be a trivial test, but this perception is deceiving. Almost everyone can agree that with the criticality of microbiological tests, it is extremely important that culture media performs properly. Culture media is used in most assays in a microbiology laboratory, and if the media does not properly support growth, false negative results may be obtained. Likewise, contaminated media may yield false positive results. Opinions on when and how the testing should be performed sometimes vary within the pharmaceutical industry.

This article is written with the pharmaceutical industry in mind. However, the concepts may cross over into other industries that utilize microbial culture media. The article discusses some of the guidance documents and regulatory expectations regarding media growth promotion and provides guidance on establishing a compliant growth promotion test.

Overview Of The Growth Promotion Assay

Media can be purchased in a ready-to-use format, prepared from dehydrated media, or prepared from raw materials. Regardless of how the media is prepared, it is essential that it functions properly to ensure the assay requiring the media yields accurate results. If media does not support growth, false negative results may be obtained, and potentially contaminated products may be released to consumers. Thus, the seemingly simple growth promotion test is a crucial part of any microbiological laboratory. The growth promotion test may also be known as nutritional adequacy testing, fertility testing, media challenge testing, or quality control testing of media. Throughout this article, the term growth promotion test will be used, and it encompasses the associated tests, such as sterility checks, pH checks, inhibitory assays, and indicative assays.

The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) Chapter <1116> Microbiological Control and Monitoring of Aseptic Processing Environments describes growth promotion testing as a procedure used “to demonstrate that media used in the microbiological environmental monitoring program, or in media-fill runs, are capable of supporting growth of indicator microorganisms and of environmental isolates from samples obtained through the monitoring program or their corresponding ATCC strains.”1 In general, the test is performed by inoculating a portion of media with a known level of microorganisms. The test samples are incubated for specified time intervals and temperatures. Then, the samples are observed for the expected results. In addition to observing for growth or inhibition of microorganisms, portions of media that are not inoculated with microorganisms are included in the test to verify that the media is not contaminated. The pH of media is also examined and is expected to fall within a specified range.

Detailed information on growth promotion tests is primarily described in USP Chapter <61> Microbiological Examination of Nonsterile Products: Microbial Enumeration Tests, USP Chapter <62> Microbiological Examination of Nonsterile Products: Tests for Specified Substances, and USP Chapter <71> Sterility Tests. Furthermore, the tests are similar in the European Pharmacopeia and the Japanese Pharmacopeia. Other compendial chapters may describe how to perform growth promotion testing for that particular compendial assay. For example, USP Chapter <51> Antimicrobial Effectiveness Testing states that “The growth-promoting capabilities of media used in this procedure must be established.”2

The USP Chapter <1117> Microbiological Best Laboratory Practices describes the expectations and proper handling of culture media. Each shipment of media received, or each batch of media prepared in-house (i.e., prepared in the microbiology laboratory), should be tested for growth promotion.3,4,5,6 In other words, if the same lot is received on different days, each shipment of that lot should receive a separate growth promotion test for each day of receipt. Shipping conditions could potentially alter the pH or performance of the media. In addition, improper heating or sterilizing conditions may result in a difference in color change, loss of clarity, altered gel strength, or pH drift from the manufacturer's recommended range.3

In my opinion, it is best practice to perform growth promotion testing in-house rather than relying on testing by contract laboratories or media vendors. If contract laboratories must be used, the worst-case scenario of shipment should be utilized. For example, I would recommend receiving a lot of media and then sending a sample of that lot to a contract laboratory for testing. This would provide opportunities for the media to be exposed to harsh conditions that could occur during shipping. Thus, this scenario would provide further evidence the media is acceptable for use after such treatment. On the other end of the spectrum, some contract laboratories may offer to sell media that has already undergone the growth promotion test. The downside with this convenient offering is that the media must still be shipped to its final destination. Again, this shipping could impact the ability of the media to properly support microbial growth. In addition, there would not be evidence that the growth properties of the media remained acceptable during the transportation process. This practice could potentially lead to an observation from regulators.

Receiving Shipments And Handling Media

When shipments of media arrive in the microbiology laboratory, they should be visually inspected, logged, and quarantined until the growth promotion test has been completed. Culture media should be inspected for the following:3

- Cracked containers or lids3

- Unequal filling of containers3

- Dehydration resulting in cracks or dimpled surfaces on solid medium3

- Hemolysis3

- Excessive darkening or color change3

- Crystal formation from possible freezing3

- Excessive number of bubbles3

- Microbial contamination3

- Status of redox indicators (if appropriate) 3

- Lot number and expiry date3

- Sterility of the media3

- Fluid thioglycollate medium (FTM) with indicator (resazurin) should be inspected to ensure that no more than the upper one-third of the bottle is pink. The pink color indicates oxygen in the media.6

Media should be labeled properly with batch or lot numbers, preparation and expiration dates, and media identification information.3 Media must be received and placed in the proper storage environment as soon as possible. Most media vendors will possess shipping validation data demonstrating the media will pass quality controls tests after transportation. However, if the end user does not properly handle the media upon receipt, the vendor may not honor a customer claim that the media failed growth promotion testing at the end user’s facility.

Media that is prepared in-house should be processed and handled according to internal standard operating procedures (SOPs). In order to establish the proper storage conditions and expiration dates of media prepared in-house, growth promotion stability studies can be developed and executed.

Selection Of Microorganisms

The microorganisms used by media vendors for their release testing may differ from those described in the compendial chapters. Media vendors are preparing media for many different types of microbiology laboratories and may risk-assess their challenge panel of microorganisms to satisfy as many industries as possible. To establish a compliant test, I recommend that the end user growth promote its media using the microorganisms and specifications listed in the compendial chapters and its own standard operating procedures rather than the microorganisms used by the vendor.

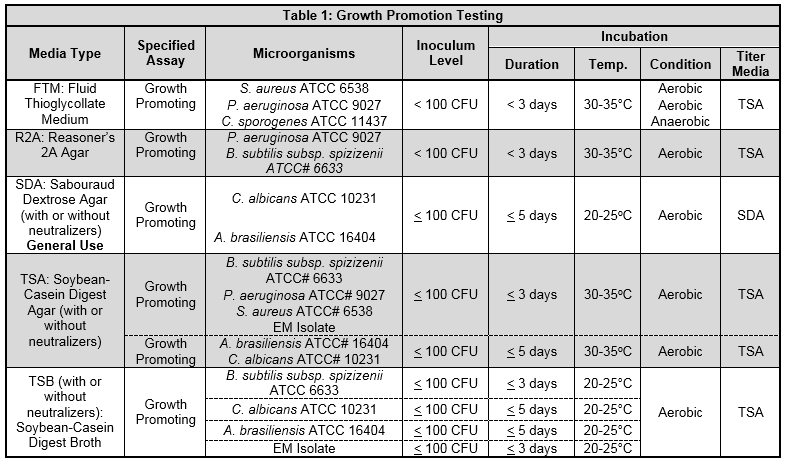

Table 1 provides an example of a compliant growth promotion testing scheme for some common culture media types utilized in the pharmaceutical industry.

The test organisms may be selected from the appropriate compendial test chapter, based on the manufacturer's recommendation for a particular medium or may include representative environmental isolates.3 The compendial chapters also provide a list of different strains of microorganisms that can be used in place of the microorganisms listed in Table 1. It is important to note that the total number of passages from the original isolate strain used for the assay should not exceed five passages from the original culture.7

A regulatory expectation that environmental isolates are incorporated into the growth promotion test is gaining momentum. The rationale for deciding which environmental isolates to include in the assay should be established and documented. One practice of choosing environmental isolates is to trend the recovered isolates, determine which microorganisms are the most predominant in the facility, and then use scientific rationale to decide which microbial isolates are appropriate to include in the growth promotion assay.

This regulatory expectation is demonstrated in observations issued by the FDA. One warning letter dated Oct. 29, 2010 states “Your firm does not perform challenge testing to the sterility media with environmental isolates from the environmental monitoring program.”8 A 483 observation from the FDA dated May 15, 2013 states “Environmental isolates used during growth promotion testing of prepared and purchased media only include gram positive organisms for growth promotion purposes. Environmental isolates do not include gram negative organisms, molds, and yeasts…”9

Although regulatory observations are occurring for the use of environmental isolates in the growth promotion assay, not all microbiologists agree with this practice.

Additional Testing Requirements

After the incubation of the samples, it is good practice to confirm that the colony morphology and the Gram stains of the recovered microorganisms are typical of the inoculated microorganisms. This will provide data that the isolates recovered from the assay were the expected microorganisms to be recovered and not from contamination.

In addition to the properties of growth promotion, the compendial chapters may require additional challenges, such as inhibitory or indicative assays. Furthermore, the sterility of the media must be confirmed.

The pH of the media from each lot received or prepared in-house should be measured after the media has tempered to room temperature (20 to 25°C). After aseptically withdrawing a sample for testing, it is recommended to use a flat pH probe for agar surfaces or an immersion probe for liquids to measure the pH.3 The pH of media should be within a range of ±0.2 of the value indicated by the manufacturer on the certificate of analysis (CoA), unless a wider range is acceptable by the validated method.3

After all of the required testing challenges have been completed, the media may be deemed acceptable for use if the following criteria are met.

- Visual evidence of growth appears within the time specified on both inoculated samples.4

- The media reacts as expected for the properties being challenged (i.e., if inhibitory, no growth should be detected).5

- The colony counts between the duplicate replicate plates should be within 50 percent of one another.

- The average of the recovered colony forming units (if applicable) and the average of the titer counts of the challenged inoculums are within 50 percent of one another.4

- Colony morphology and Gram stain, if applicable, are typical of the inoculated microorganisms.

- The pH of media is within a range of ±0.2 of the value indicated by the manufacturer on the CoA, unless a wider range is acceptable by a validated method.3

In the event that a batch of media does not meet the requirements of growth promotion testing, an investigation should be initiated to identify the cause of the nonconformance and corrective/preventive action plans should be addressed.3 If the media was purchased from a vendor, the vendor should be notified of the discrepancy. Nonconforming lots should not be used for testing unless an assignable cause and a corrective resolution can be achieved.3

A warning letter from the FDA dated Aug. 29, 2018 also speaks to the expectations of the growth promotion test. The warning letter states, “…Your firm did not perform quality control testing on [REDACTED] prepared media to ensure the media support growth and acceptable recovery during testing. You lacked a program that includes quality control testing of all prepared media for its quality attributes, such as pH, and growth promotion prior to use in testing customers’ OTC drug products and components. Our investigators observed that you did not have any microorganisms stored at your facility and did not have the test strains and specified microorganisms for completing microbiological testing. You were not able to provide purchasing records for any reference microorganisms or test strains.”

Conclusion

Microbiological assays are critical to patient safety, product release, and maintaining the manufacturing environment. Most assays require the use of culture media. For accurate and reliable results, it is essential that culture media performs properly. This can be challenged with the growth promotion test. The growth promotion test is mainly described in USP Chapter <61>: Microbiological Examination of Nonsterile Products: Microbial Enumeration Tests, USP Chapter <62>: Microbiological Examination of Nonsterile Products: Tests for Specified Substances and USP Chapter <71>: Sterility Tests. Other compendial chapters describe growth promotion as it pertains to the assay in question, such as the Antimicrobial Effectiveness Test USP <51>.

Remember that each shipment of media received, or each batch of media prepared in-house, should be tested for growth promotion and the associated tests.3 The test should be designed according to the compendial chapters and should incorporate environmental isolates as necessary.

When the growth promotion test is compliant with compendial chapters and regulatory expectations and is properly executed according to established SOPs, microbial data obtained from assays that utilized culture media generates more trustworthy results.

References:

- United States Pharmacopeia (USP) <1116> Microbiological Evaluation of Cleanrooms and Other Controlled Environments.

- United States Pharmacopeia (USP) <51> Antimicrobial Effectiveness Testing

- United States Pharmacopeia (USP) <1117> Microbiological Best Laboratory Practices

- United States Pharmacopeia (USP) <61> Microbiological Examination of Nonsterile Products: Microbial Enumeration Test

- United States Pharmacopeia (USP) <62> Microbiological Examination of Nonsterile Products: Tests for Specified Microorganisms

- United States Pharmacopeia (USP) <71> Sterility Tests

- PMM (2014), Pharmaceutical Microbiology Manual, Version 1.2, ORA. 007, March 30, 2015. Accessed on December 20, 2018 at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/ScienceResearch/FieldScience/UCM397228.pdf

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Warning Letters. Accessed on December 20, 2018 at http://www.fda.gov/ICECI/EnforcementActions/WarningLetters/

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA) ORA FOIA Electronic Reading Room. Accessed on December 20, 2018 at https://www.fda.gov/aboutfda/centersoffices/officeofglobalregulatoryoperationsandpolicy/ora/oraelectronicreadingroom/default.htm

About the Author:

Crystal M. Booth, M.M., is a regional manager with PSC Biotech. She has over 19 years of experience in pharmaceutical microbiology, working in quality assurance, CDMOs, R&D, and quality control laboratories, including startup companies. During her career, she has developed and validated methods for antibiotics, otic products, topical creams, topical ointments, oral solid dose products, oral liquid dose products, veterinary products, human parenterals, vaccines, biologics, aseptically filled products, and terminally sterilized products. Those methods include microbial limits testing, bacterial endotoxins testing, particulate testing, sterility testing, pharmaceutical water system validations, environmental monitoring programs, surface recovery validations, disinfectant efficacy studies, minimum inhibitory concentration testing, antimicrobial effectiveness testing, hold time studies, and various equipment validations. Crystal earned her bachelor’s degree in biology from Old Dominion University and her masters in microbiology from North Carolina State University.

Crystal M. Booth, M.M., is a regional manager with PSC Biotech. She has over 19 years of experience in pharmaceutical microbiology, working in quality assurance, CDMOs, R&D, and quality control laboratories, including startup companies. During her career, she has developed and validated methods for antibiotics, otic products, topical creams, topical ointments, oral solid dose products, oral liquid dose products, veterinary products, human parenterals, vaccines, biologics, aseptically filled products, and terminally sterilized products. Those methods include microbial limits testing, bacterial endotoxins testing, particulate testing, sterility testing, pharmaceutical water system validations, environmental monitoring programs, surface recovery validations, disinfectant efficacy studies, minimum inhibitory concentration testing, antimicrobial effectiveness testing, hold time studies, and various equipment validations. Crystal earned her bachelor’s degree in biology from Old Dominion University and her masters in microbiology from North Carolina State University.