How To Ensure QMS Continuity During Leadership Transition

By Mark Durivage, Quality Systems Compliance LLC

Continuity of quality management system (QMS) leadership during a transition is a very serious issue within the life  sciences industry. Many organizations with very robust QMSs routinely find themselves in a state of disarray and facing compliance issues when key members of the quality leadership team leave the organization.

sciences industry. Many organizations with very robust QMSs routinely find themselves in a state of disarray and facing compliance issues when key members of the quality leadership team leave the organization.

During one stretch in 2017, five of the 15 scheduled audits that I performed had leadership transitions that significantly impacted the effectiveness of the QMS. So, you might ask, why were there issues? The simple answer is that management did not realize who was responsible for what. This article will present some techniques and tools to help minimize the possibility of a QMS meltdown while optimizing continuity during leadership transitions.

The Hawthorne Effect was conceived by Henry A. Landsberger in 1958 after analyzing experiments conducted from 1924 to 1932 at the Hawthorne Works in Cicero, Illinois. The Hawthorne effect is the principle that what gets measured gets done. Although there is controversy regarding Landsberger’s conclusion, individuals will complete tasks when they (individuals) know the results are being measured, monitored, and compared. The Hawthorne Effect can be leveraged to ensure QMS continuity during leadership transitions.

Requirements And Background

Pharmaceutical and medical device regulations, standards, and guidances provide direction and lay out the framework for successfully implementing, maintaining, and sustaining an effective and robust quality management system. Specifically, ICH Guideline Pharmaceutical Quality System Q10 and 21 CFR 820, Quality System Regulation, include requirements that address QMS leadership issues including, but not limited to, the following:

ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline Pharmaceutical Quality System Q10

1.6.1 Knowledge Management

Product and process knowledge should be managed from development through the commercial life of the product up to and including product discontinuation. For example, development activities using scientific approaches provide knowledge for product and process understanding. Knowledge management is a systematic approach to acquiring, analyzing, storing and disseminating information related to products, manufacturing processes and components. Sources of knowledge include but are not limited to prior knowledge (public domain or internally documented); pharmaceutical development studies; technology transfer activities; process validation studies over the product life cycle; manufacturing experience; innovation; continual improvement; and change management activities.

2.1 Management Commitment

(b) Management should:

(1) Participate in the design, implementation, monitoring and maintenance of an effective pharmaceutical quality system;

(2) Demonstrate strong and visible support for the pharmaceutical quality system and ensure its implementation throughout their organization;

(3) Ensure a timely and effective communication and escalation process exists to raise quality issues to the appropriate levels of management;

(4) Define individual and collective roles, responsibilities, authorities and inter-relationships of all organizational units related to the pharmaceutical quality system. Ensure these interactions are communicated and understood at all levels of the organization. An independent quality unit/structure with authority to fulfil certain pharmaceutical quality system responsibilities is required by regional regulations;

(5) Conduct management reviews of process performance and product quality and of the pharmaceutical quality system;

3.2.1 Process Performance and Product Quality Monitoring System

Pharmaceutical companies should plan and execute a system for the monitoring of process performance and product quality to ensure a state of control is maintained. An effective monitoring system provides assurance of the continued capability of processes and controls to produce a product of desired quality and to identify areas for continual improvement.

3.2.4 Management Review of Process Performance and Product Quality

Management review should provide assurance that process performance and product quality are managed over the life cycle. Depending on the size and complexity of the company, management review can be a series of reviews at various levels of management and should include a timely and effective communication and escalation process to raise appropriate quality issues to senior levels of management for review.

(a) The management review system should include:

(1) The results of regulatory inspections and findings, audits and other assessments, and commitments made to regulatory authorities;

(2) Periodic quality reviews, that can include:

(i) Measures of customer satisfaction such as product quality complaints and recalls;

(ii) Conclusions of process performance and product quality monitoring;

(iii)The effectiveness of process and product changes including those arising from corrective action and preventive actions.

(3) Any follow-up actions from previous management reviews.

(b) The management review system should identify appropriate actions, such as:

(1) Improvements to manufacturing processes and products;

(2) Provision, training and/or realignment of resources;

(3) Capture and dissemination of knowledge.

21 CFR Part 820, Quality System Regulation

Sec. 820.20 Management responsibility.

(b) Organization. Each manufacturer shall establish and maintain an adequate organizational structure to ensure that devices are designed and produced in accordance with the requirements of this part.

(1) Responsibility and authority. Each manufacturer shall establish the appropriate responsibility, authority, and interrelation of all personnel who manage, perform, and assess work affecting quality, and provide the independence and authority necessary to perform these tasks.

(3) Management representative. Management with executive responsibility shall appoint, and document such appointment of, a member of management who, irrespective of other responsibilities, shall have established authority over and responsibility for:

(i) Ensuring that quality system requirements are effectively established and effectively maintained in accordance with this part; and

(ii) Reporting on the performance of the quality system to management with executive responsibility for review.

(c) Management review. Management with executive responsibility shall review the suitability and effectiveness of the quality system at defined intervals and with sufficient frequency according to established procedures to ensure that the quality system satisfies the requirements of this part and the manufacturer's established quality policy and objectives. The dates and results of quality system reviews shall be documented.

The requirements mentioned above speak directly about preventing a QMS meltdown while optimizing leadership continuity during management transitions. Although these clauses are from the pharmaceutical and medical device industries, these principles can be applied to virtually any quality management system in the life sciences industry.

Responsibilities And Authority

Visibility is paramount to maximizing Landsberger’s Hawthorne Effect. Clearly defining organizational roles, responsibilities, and authorities is the foundation of providing QMS visibility to management. Management must ensure responsibilities and authorities for relevant roles are assigned, communicated, and understood within the organization Only by defining organizational roles, responsibilities, and authorities can an organization properly function.

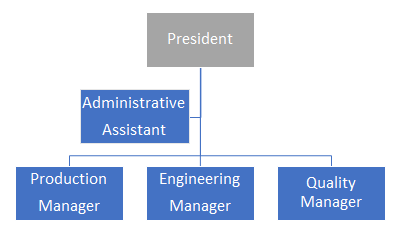

Organizational charts are commonly used to show the organization’s departmental or company hierarchy. Most organizations will develop an organizational chart using job titles, which are usually the functional roles (but not always), and the names of the associated individuals. Charts that contain names can be very difficult to maintain in organizations that have significant growth or high employee turnover. There are software programs that maintain “live” organizational charts that are directly linked to the human resource module. Whether the organizational chart is generated manually or automatically, organizational charts should be identified by a version and/or effective date for compliance purposes. A basic organizational chart is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Organizational chart

Organizational charts should be supported by job descriptions. The job titles on the organizational chart and job descriptions should align, with the job titles being descriptive of the functional roles. For example, the common job title of quality manager may be listed as quality leader on the chart. While the title of “quality manager” is commonly used and widely understood, “quality leader” is not. As a result, an auditor would likely have to ask for the quality leader’s job description, which may not be the case if “quality manager” is used.

Three quick best practices are to designate the management representative and/or responsible person on the organizational chart, ensure the job descriptions are signed by the individuals currently holding the positions, and ensure each job description is identified by a version and/or effective date for compliance purposes.

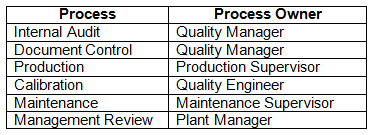

Another method to clearly define organizational roles is to use a responsibility matrix. A responsibility matrix contains a list of activities, such as, for example, quality management system processes and their corresponding process owners. This is a very useful tool for management to quickly know who is responsible for which activity, especially when an employee leaves the organization. Figure 2 is an example of a high-level responsibility matrix. The processes can be further broken down into more detailed tasks, such as, for example, audit planning, audit execution, audit reporting, audit metrics, etc.

Figure 2: Responsibility matrix

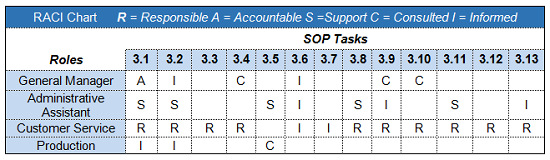

Another method for clearly defining organizational roles is the responsible accountable support consulted informed (RASCI) model. The RASCI model is commonly used in standard operating procedures and work instructions to clearly delineate responsibility and authority. The five roles in a RASCI model are:

- Responsible: “Responsible” refers to the individual whose function is completing the task or deliverable. This role is also known as the “Doer.” To determine this role, ask who is responsible for carrying out the specific task.

- Accountable: The individual who is “Accountable” has the final authority or accountability for the task’s completion. This function has the ultimate decision-making authority and cannot delegate the authority to another function. To determine this role, ask who is responsible for the task and who is responsible for what has been done.

- Support: Individuals that “Support” the implementation of the task provide the resources necessary to complete the task. To determine this role, ask who provides support during the implementation of the task.

- Consulted: The function that is labeled “Consulted” is an adviser to a task. This individual provides advice needed to successfully complete the task. To determine this role, ask who can provide valuable advice or consultation for the task.

- Informed: Those who are considered “Informed” are kept up to date on task completion. Individuals who perform this function are notified once the task is completed. To determine this role, ask who should be informed about the task progress or the decisions in the task.

Figure 3 is an example of the RASCI model applied to the requirements of a hypothetical standard operating procedure (SOP). The matrix indicates the general manager is ultimately accountable for the procedures, and the general manager, administrative assistant, customer service, and production are involved in this process.

Figure 3: RASCI matrix

Monitoring, Measurement, And Analysis

What gets measured gets done. If processes are not measured and analyzed, it is difficult to know how the organization is performing. There are several tools that can be used for monitoring, measuring, and analyzing processes. Among the most commonly used are run charts, control charts, bar graphs, pie charts, and Pareto charts (see Using Trending As A Tool For Risk-Based Thinking).

Some of the most important processes to monitor, measure, and analyze are corrective and preventive action (CAPA), complaints, nonconformances, production processes, service activities, maintenance, calibration, training, supplier performance, internal audits, and external audits, to name a few. If these processes are routinely monitored, measured, and analyzed, these efforts can help an organization properly function when there are transitions in leadership.

I highly recommend that if your organization requires that a process be monitored, measured, and analyzed, they (process metrics) should be reviewed during weekly/monthly staff meeting and not just annually during management review.

If monitoring, measuring, and analyzing processes become part of the routine during regular staff meetings, when individuals leave an organization it will be clear when an individual’s tasks are not being completed, providing visibility to management, and allowing management to delegate or otherwise ensure the tasks will be completed.

Management Review

The QMS responsibilities, monitoring, measurement, and analysis provide the inputs into the management review process and support the requirements for organizational knowledge.

Generally, management reviews are conducted annually. However, this minimalist approach can lay the groundwork for a QMS meltdown and increase regulatory and compliance risk when quality leaders such as managers or directors leave the organization.

Conclusion

The discussion above focuses on providing management visibility to ensure the effectiveness and efficiency of the QMS and enhance continuity during leadership transitions.

I cannot emphasize enough the importance documenting the tools and methods used. The approaches presented in this article can and should be utilized based upon industry practice, guidance documents, and regulatory requirements.

References:

- Durivage, M.A., 2017, Contingency Plans: An Essential Quality Management System Risk Tool, Life Science Connect.

- Durivage, M.A., 2017, The Certified Supplier Quality Professional (CSQP), Milwaukee, ASQ Quality Press

- Durivage, M.A., 2018, Using Trending As A Tool For Risk-Based Thinking, Life Science Connect.

About the Author:

Mark Allen Durivage is the managing principal consultant at Quality Systems Compliance LLC and an author of several quality-related books. He earned a BAS in computer aided machining from Siena Heights University and an MS in quality management from Eastern Michigan University. Durivage is an ASQ Fellow and holds several ASQ certifications, including CQM/OE, CRE, CQE, CQA, CHA, CBA, CPGP, CSQP, and CSSBB. He also is a Certified Tissue Bank Specialist (CTBS) and holds a Global Regulatory Affairs Certification (RAC). Durivage resides in Lambertville, Michigan. Please feel free to email him at mark.durivage@qscompliance.com with any questions or comments, and connect with him on LinkedIn.

Mark Allen Durivage is the managing principal consultant at Quality Systems Compliance LLC and an author of several quality-related books. He earned a BAS in computer aided machining from Siena Heights University and an MS in quality management from Eastern Michigan University. Durivage is an ASQ Fellow and holds several ASQ certifications, including CQM/OE, CRE, CQE, CQA, CHA, CBA, CPGP, CSQP, and CSSBB. He also is a Certified Tissue Bank Specialist (CTBS) and holds a Global Regulatory Affairs Certification (RAC). Durivage resides in Lambertville, Michigan. Please feel free to email him at mark.durivage@qscompliance.com with any questions or comments, and connect with him on LinkedIn.