How 'Explainable ML' Can Improve Process Performance

By Lukas Gerstweiler and Zhen Zhang, University of Adelaide

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have revolutionized industries from finance to pharmaceuticals, with high-profile successes such as DeepMind’s AlphaFold, which dramatically advanced protein structure prediction. Yet, the bioprocessing sector has been slower to adopt AI for process development, control, and analysis. One key hurdle is the limited availability of experimental data. Generating comprehensive data sets can be prohibitively expensive and time-consuming, slowing the training of robust AI models.

Additionally, while mechanistic models provide interpretable insights into processes, many AI approaches function as “black boxes,” offering predictions without clarity on how or why those predictions are made. This lack of transparency undermines trust among biomanufacturing professionals who need both accurate forecasts and deeper mechanistic understanding.

A promising solution lies in harnessing established techniques from other AI-heavy domains — most notably, image analysis. By applying “explainable” machine learning to repurposed image-classification models, we can gain more than just predictive power; we can uncover hidden process relationships. This strategy combines transfer learning (adapting pretrained networks to new tasks) with algorithms like gradient-weighted class activation mapping (Grad-CAM) that highlight which data features drive a model’s predictions. Ultimately, explainable ML can help biomanufacturers navigate process complexities, maintain product quality, and optimize operational parameters without requiring massive bespoke data sets.

A Case Study: Imaging Chromatography Column DBC

Biomanufacturing processes, such as continuous chromatography, hinge on column performance factors like dynamic binding capacity (DBC). The DBC degrades over repeated cycles due to fouling, protein buildup, or other changes in column resin properties. Conventional strategies rely on empirical heuristics to manage these variations, potentially causing suboptimal performance or unplanned downtime.

In other industries, AI-based solutions excel at identifying subtle changes in massive data sets, as seen in image recognition tasks for self-driving cars or medical diagnostics. However, direct application of these techniques to biomanufacturing is complicated by data limitations. Whereas image recognition systems often draw on millions of labeled pictures, bioprocess engineers typically have access to only a few dozen or hundreds of runs. Moreover, the field demands not just predictions but understanding: A seemingly accurate model is less useful if it can’t explain why a particular column is failing or how certain sensor signals correlate with performance.

This is where transfer learning and explainable ML come in. By adapting advanced, pretrained image analysis models to interpret standard process signals (UV, pressure, conductivity, etc.), researchers can glean meaningful insights from relatively modest data sets. Explaining the model’s rationale, rather than just showing output, grants unprecedented clarity into bioprocess performance.

Transforming Process Signals Into ‘Images’

To address scarcity, we borrowed a concept from image classification, where convolutional neural networks (CNNs) often excel. Traditional CNNs are trained on vast image libraries like ImageNet. In bioprocessing, by converting sensor data into an artificial “image,” we can tap into these powerful pretrained models — a technique known as transfer learning.

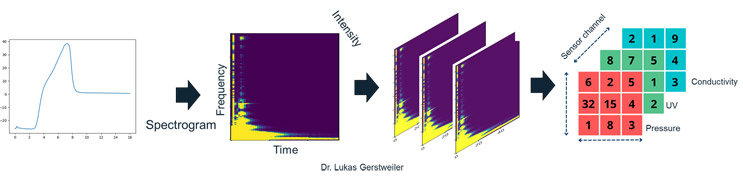

For instance, consider a continuous chromatography process with sensor outputs for UV, pressure, and conductivity. We transform these signals into spectrogram “channels,” analogous to red, green, and blue in standard images. Each sensor trace over time is rendered as one color channel, resulting in a composite image. Pretrained networks such as ResNet can then be fine-tuned by replacing only the final classification layer while keeping the learned feature-detection layers intact. Figure 1 outlines the general workflow of transferring process sensor data into “images.”

Figure 1: Converting Sensor Signals Into Artificial “Images.” This flowchart demonstrates how raw signals (e.g., UV, pressure, conductivity) are converted into spectrograms and combined into red, green, and blue (RGB) channels. This approach enables the fine-tuning of pretrained image classification models for biomanufacturing applications.

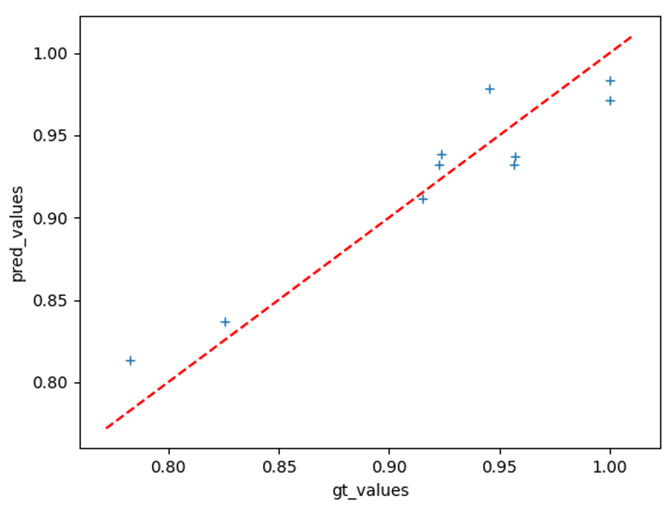

Predicting Dynamic Binding Capacity And Fouling

In our current research, we used data from the equilibration and wash phases to predict DBC values, enabling real-time monitoring of column status and optimal process conditions. By training a robust model on sensor data from only four columns, we significantly reduced the time and expense compared to generating the millions of data points typically required for large neural networks. Early tests show that this transfer-learning approach yields predictions strongly correlated with measured DBC (Figure 2). Once adapted, the model can flag potential fouling or performance drops well before they become critical, allowing proactive process adjustments.

Figure 2: Predicted versus measured values of dynamic binding capacity (DBC) from wash and equilibration data using a fine-tuned image classification network.

Explainable AI: From Predictions To Insights

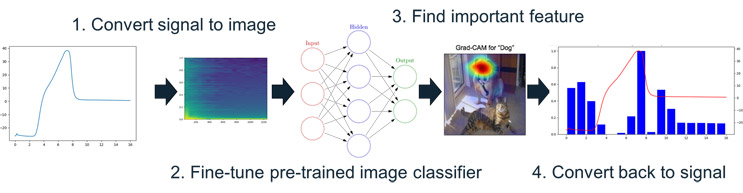

Beyond predicting column performance, we utilized explainable AI algorithms such as Grad-CAM to uncover how the model arrives at its conclusions. In traditional image analysis, Grad-CAM might highlight a dog’s ears or snout as key features distinguishing it from a cat. Translated to our artificial “images,” Grad-CAM highlights sensor data regions — specific signals or time intervals — most influential in predicting low or high DBC.

In practice, we found that UV280 readings during wash steps were highly predictive of decreasing DBC, while conductivity or pressure data were less significant. This lines up well with established process knowledge (UV monitoring protein presence), yet the strength of the correlation emerged without explicit assumptions. That not only validates the approach but also demonstrates its utility in identifying hidden or underappreciated parameters. The general workflow is outlined in Figure 3.

Figure 3: High-Level Workflow For Explainable ML In Biomanufacturing. First the raw sensor signals are converted into artificial images, which are then used to fine-tune a pretrained image-classification. Explainable machine techniques are then used to highlight important features on the artificial images (made out of sensor signals). Finally, this is converted back to the original sensor signals to identify relevant sensors and time periods in the process for practical process insights.

Toward A New Paradigm

By applying pretrained networks, we reduce the experimental burden. By incorporating explainable ML, we transform biomanufacturing data analysis from a black box to a transparent window, showing exactly which factors drive performance shifts. This capability is particularly valuable in large-scale operations where slight variations in feed composition or equipment function can have major downstream consequences.

Ultimately, the synergy of transfer learning and explainable AI empowers process engineers to optimize bioprocesses more strategically, minimize downtime through preventive interventions, and uncover novel correlations. Such a paradigm could markedly improve product yields and quality while controlling costs in an industry where the stakes — including patient safety — are incredibly high.

Translating At Industrial Scale

Despite its promise, this approach has only been validated in a laboratory setting so far. Translating these methodologies to industrial or large-scale operations will require thorough testing to confirm both predictive accuracy and adaptability. For example, real-world biomanufacturing lines often experience unplanned disruptions, such as sensor drift, that are less common in controlled lab experiments.

Moreover, regulatory concerns may complicate the implementation of AI-driven control strategies. Agencies increasingly expect robust process understanding, and while explainable ML helps address the “black box” issue, regulators may still require additional mechanistic justification. Integrating these AI models into existing manufacturing execution systems (MES) also poses practical challenges, from data standardization to staff training.

Finally, the necessity of converting sensor signals into artificial “images” might raise questions about data integrity and fidelity. If the transformation process is too aggressive, it could obscure subtle but critical signal variations. These considerations underscore the importance of systematic validation and stakeholder engagement before rolling out explainable ML tools at scale.

Conclusion

Explainable ML has the potential to reshape bioprocessing by offering both predictive power and profound insights into underlying mechanisms. By adapting well-established image classification models, companies can sidestep the high costs of generating massive data sets. The resulting “transfer learned” networks are then paired with interpretability tools like Grad-CAM to pinpoint which signals — and at which times — drive key performance metrics.

In doing so, biomanufacturers can respond proactively to column fouling or other deviations, refining parameters for optimal productivity. The ability to see why the model makes certain predictions is a game changer, building trust among process engineers and regulators alike. Although further validation is necessary in full-scale industrial contexts, early findings suggest that this framework can unlock new efficiencies, highlight unknown correlations, and facilitate continuous improvement in bioprocessing operations.

Taken together, these techniques introduce a powerful new paradigm for exploring complex biological systems — one that merges the strengths of machine learning with the clarity needed to manage critical manufacturing processes reliably and safely.

About The Authors:

Lukas Gerstweiler is a lecturer in chemical engineering at the University of Adelaide, where he leads the Biomanufacturing Research Group. His work focuses on continuous biomanufacturing, virus-like particle production, and chromatographic purification methods. His research aims to streamline industrial bioprocessing while enhancing product quality. Connect with him on LinkedIn for more information about his latest projects in applying explainable AI and data-driven techniques to advance biomanufacturing. Visit his group’s website here to learn more about their research.

Lukas Gerstweiler is a lecturer in chemical engineering at the University of Adelaide, where he leads the Biomanufacturing Research Group. His work focuses on continuous biomanufacturing, virus-like particle production, and chromatographic purification methods. His research aims to streamline industrial bioprocessing while enhancing product quality. Connect with him on LinkedIn for more information about his latest projects in applying explainable AI and data-driven techniques to advance biomanufacturing. Visit his group’s website here to learn more about their research.

Zhen Zhang is a senior research fellow in the School of Computer Science at the University of Adelaide, where his research centers on machine learning and causality, with applications in computer vision and data science. His work in causal discovery, graph neural networks, and probabilistic graphical models has been recognized in conferences and journals, including NeurIPS, CVPR, and JMLR. Dr. Zhang has also contributed to collaborative projects in diverse fields such as chemistry and computational fluid dynamics. Connect with him on LinkedIn or visit his website at zzhang.org to learn more about his research and collaborations.

Zhen Zhang is a senior research fellow in the School of Computer Science at the University of Adelaide, where his research centers on machine learning and causality, with applications in computer vision and data science. His work in causal discovery, graph neural networks, and probabilistic graphical models has been recognized in conferences and journals, including NeurIPS, CVPR, and JMLR. Dr. Zhang has also contributed to collaborative projects in diverse fields such as chemistry and computational fluid dynamics. Connect with him on LinkedIn or visit his website at zzhang.org to learn more about his research and collaborations.