8 Critical Elements Of A Supply Chain Strategy — From Discovery To Commercialization

By Carla Reed, president, New Creed LLC

The road from discovery of a promising molecule through the stages of clinical trials and final approval can be a challenging one. The rewards, however, are great — bringing a life-saving drug product to the point where it fulfills the promises of the early days of exploration cannot be overstated!

The journey may take years, during which there are many different players who have roles to fulfill. Suppliers of the materials and equipment to the laboratory where the first discovery is made are in many cases replaced by larger players with capabilities to provide a broader range of materials, services, and support. In many cases, even the team of scientists who were key in the initial stages will be replaced by experts in larger-scale production, in preparation for scaling up to a sustainable commercial supply model. A twist on this is the increasing trend to outsource the majority of these activities to contract research and manufacturing organizations, creating a virtual operation that requires collaboration and ongoing communication.

During this evolution there are many lessons to be learned, not the least of which is that it is imperative to take into account the nuances of supply chain management that can make the difference between success and failure. The ultimate prize — delivering the life-saving (or life-changing) substance to the point of care — takes careful planning, leaving no stone unturned, to ensure that risk factors are evaluated and a clearly defined strategy is in place.

The first step on the path to delivering a successful commercial supply chain strategy is to review the business strategy, ensuring that all elements of the storage and distribution network align with the mission and business goals of the enterprise and, more importantly, with the needs of caregivers and patients.

At a high level, the following are important factors that need to be evaluated and integrated into the plan.

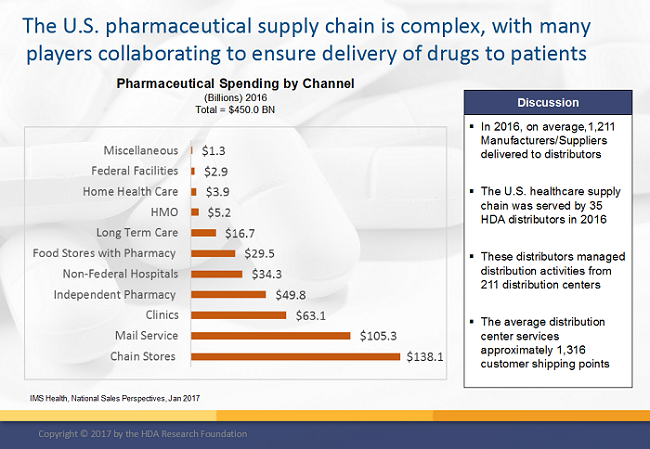

- Access to therapy and availability through preferred channels – Many new biological and pharmaceutical products are administered in a clinical environment, with either in-patient or out-patient settings. Distribution models should support the current acquisition channel for related therapies, ensuring access to the product for providers and the patients they administer to.

- Inventory staging prior to commercial release – Demand planning should include identification of quantity and location for placement and replenishment of inventory to support projected demand and delivery channels once the product has been approved and orders are filled.

- Service and supply – Order fulfillment models should be developed and refined to ensure that new therapies can be acquired in a timely and cost-effective manner, enhancing the overall provider and patient experience.

- Regulatory compliance – Awareness and understanding of guidelines and regulations for the storage and distribution of pharmaceuticals are critical. This includes compliance with regulations (current and planned) that should be adhered to in order to ensure the authenticity, safety, and security of the product.

Elements of the strategy to transition from an exploratory stage to a clinical one, and finally to a commercial supply chain, should include the following eight elements.

1. Supply Chain Strategy

An extension of the product development and business strategy, the supply chain strategy is a combination of policies, processes, and procedures that should be followed to ensure delivery of the final product from point of manufacturer through administration to patient.

When developing the overall supply chain strategy and implementation plan, these factors should form part of the evaluation criteria for various operational models. In addition, the strategy should take into consideration the three primary flows that need to be managed in the commercial supply chain:

- Material flow – packaging, transportation, receipt, and disposition across the end-to-end chain of custody, maintaining visibility as goods are moved across the supply chain into the chain of care

- Financial flow – during the product conversion cycle there are value-added activities and processes that increase the commercial value that need to be tracked across the cash to cash cycle. It is also important to monitor and track triggers for transfer of ownership and liability.

- Information flow – information systems support and information integration to facilitate a digital data trail that provides a “single version of the truth” for each of the activities and transactions across the product and shipment life cycle

The commercial supply chain strategy and plan should cover risk evaluation, distribution planning, execution, and logistics activities. This includes, but is not limited to, the following:

- Scheduling the logistics process – to include provision of applicable packaging materials for product protection, with associated time and temperature indicators

- Shipment planning – risk assessments for shipment of both drug substance and drug product

- Execution of planned packaging and shipment process – tracking product state, elapsed time, and temperature excursions

- Receipt and unpacking of shipment – inspection and QA

- Exception management and alerting

In the case of new products for companies with an existing portfolio and distribution channels, it is appropriate to identify any additional considerations that should be planned for. For companies where the supply chain has not yet been defined, it is necessary to determine product, market, and customer requirements. These can then be reviewed and the strategy developed for the transportation, storage, and delivery to the patient site. Any special handling requirements, particularly for environmentally sensitive products, should be documented and integrated into the product and material handling profile. Information related to risk factors and mitigation strategies — for example, special packaging, labeling, and material handling instructions — must be included.

Biologics — and in particular specialty biopharmaceutical products with small patient populations, short shelf life, and certain environmental management and control needs — require different capabilities than more traditional small molecule pharmaceutical products. Batch sizes tend to be smaller, with fewer batches produced and variations on the storage and distribution models to support in-network transformation — for example, unit-level packaging, kitting, labeling, and reverse logistics for responsible disposal of returned product and/or material.

Traditional supply chain models do not necessarily meet the needs of these specialty pharmaceutical products — new approaches need to be adopted, in collaboration with partners and providers as needed. In response to these growing needs, new services have been developed by a variety of third-party entities, who understand specific industry and market needs for a variety of therapies. Collaboration across specialty pharmaceutical distributors, third-party logistics companies, packaging, labeling, and information technology providers has provided a wide range of optional services that are available. These include, but are not limited to:

- Financial management – order to cash cycle

- Regulatory compliance – regional, local, and global

- Payment models – coding and reimbursement support

- Customer service and patient assistance programs

2. Inventory Management – Demand and Supply Planning

In an extended network across the product life cycle, there are different types of inventory, including work in progress, finished goods in bulk state, packaged, and saleable units.

For new products where the demand is relatively unknown — or unpredictable — maintaining a balance between supply and demand requires close collaboration between all participants in the chain of care. It is important to define functional requirements to enable collaboration across a network of partners.

Managing the disposition of inventory to support different packaging, labeling, or material handling requirements requires an understanding of the nuances of risks and constraints within the operational environments of these stakeholders. Different fulfillment models should be reviewed with stakeholders, ensuring ease of access to product. This can be facilitated through a combination of inventory management strategies, including — but not limited to — provider managed inventory and/or consignment inventory.

Capabilities required for inventory management and control should be clearly defined in user requirements specifications (URSs) across the value chain from production of the drug substance to drug product filling and packaging operations (unit of use) through final packaging, labeling, and delivery to the clinical setting and point of patient.

3. Packaging Strategy

The packaging strategy is a subset of the overall business and operations policy and the related supply chain strategy. Packaging is an integral part of each product and, in addition to aesthetics, marketing functions, and brand awareness, should preserve the stability and integrity of the packaged unit. In addition, in the case of products that are susceptible to environmental conditions, packaging should include additional controls to ensure product integrity.

Development and implementation of the packaging strategy should integrate best practices for supply chain, one of which is postponement at the packaging level. An example of this is the shipment and storage of product in a work in process state, with final packaging (unit, composite, or other package configuration) taking place at time of order fulfillment. The advantage of such a strategy is that it provides a higher degree of flexibility, enabling pack to market or pack to patient, including any special labeling or package inserts.

Consideration of different alternatives for postponement at the final packaging level include (but are not limited to):

- Regulatory restrictions

- Inventory management and valuation

- Product risk during handling.

A further consideration is the requirement for item-level serialization in compliance with regulations within the U.S., EU, and other countries. A holistic approach, including definition in terms of package inserts required, labeling for market, serialization for compliance, and any product protective measures, such as tamper-evident seals and sensors, should be taken. The packaging strategy should be addressed by a cross functional team that includes sales/marketing, quality, regulatory, logistics, and customer advocates. Evaluation of requirements should include:

- Product level packaging, labeling – single unit package as well as bulk packaging requirements

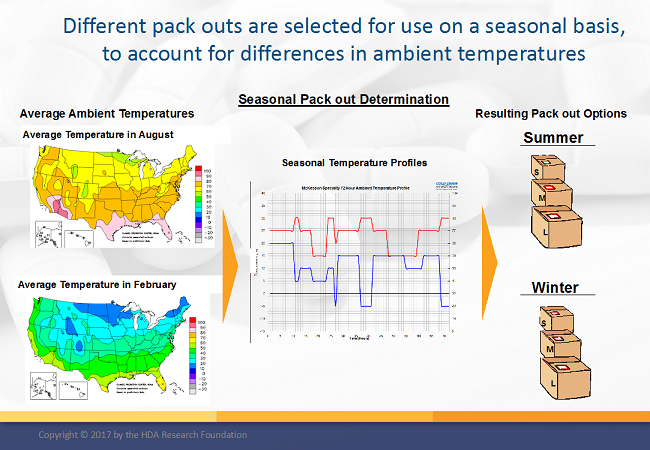

- Shipment packaging – transportation-related requirements based on product profile, risk assessment, and time and temperature restrictions/risk factors

Shipment packaging evaluation and specification should take place during development of the packaging strategy, identifying hazards that should be planned for at both a regional, global, and seasonal level. This will provide detail that should be integrated into standard operating procedures and controls for shipment planning and execution.

Note: I covered the subject of secondary packaging in a previous article.

4. Storage and Delivery Strategy

Mature products with known patient populations and related demographic profiles are relatively simple to plan for. In the case of new products, in particular novel therapies with small patient populations, limited point of care locations, and an evolving patient standard of care, it is critical to ensure that the distribution strategy supports the overall market message and patient experience. Different demand models should be considered to establish the most efficient and cost-effective network design for product storage and distribution.

In an outsourced model where the order fulfillment takes place within the distribution network, there are many considerations. This is an area that has grown in importance and is currently the focus of Guidance for Good Distribution Practices (GDP). These guidelines, which extend the controls of GMP into the distribution environment, include approaches that should be adhered to.

A key element of this is trading partner and shipment qualification, including:

- Supplier qualification: During the product life cycle, there are a variety of suppliers of raw materials and packaging components, as well as contract research and manufacturing organizations, that contribute to the overall composition and configuration of the final drug product. During the scale up to commercial production, it is necessary to reevaluate the current supplier landscape and identify any risk factors as well as additional requirements. In many cases, there will be sole and single source suppliers that may not be able to support the projected growth for commercialization. When evaluating alternative suppliers, it is appropriate to establish required service levels based on projected demand and associated supply patterns.

- Customer qualification: During the establishment of the commercial supply chain structure, it is necessary to establish customer master files with associated authorities and credit arrangements. Additional requirements for supply chain security include the qualification and authentication of all entities procuring pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical products.

- Carrier qualification: Additional security requirements, in addition to service level agreements established to ensure shipment integrity, should be complied with. This will ensure that all carriers that are engaged in the transportation of pharmaceutical products are authorized and legitimate. Based on the nature of the products — for example, controlled substances — additional screening and qualification may apply for carriers.

- Shipment planning and packaging qualification/stability studies: For every shipment where there is a variation from existing shipping lanes, modes of transportation, or product profiles, it is necessary to perform a risk assessment as part of the shipment planning process. Factors for evaluation and qualification include shipment packaging, labeling, time and temperature management, and alerting.

Note: For more information on qualifying trading partners, see my previous article on current good distribution practices (cGDPs).

5. Regulatory Compliance

The life sciences industry is highly regulated, with close cooperation between regulatory bodies and inspectors at a global level. The increase in biological drug substances and products, many of which are derived from a combination of human and animal cells, blood products, and other biological elements, has its own special challenges. Many of these materials are regulated by agencies and regional entities. When developing the supply chain strategy, it is important to consider any local or regional regulations that need to be complied with — and any global differences in associated product descriptions with related literature and support materials.

This is especially important when crossing geographical boundaries where there are compliance requirements beyond healthcare regulators. Vigilance across the extended pharmaceutical supply chain, in response to an increase in product adulteration, counterfeiting, and diversion, has resulted in a variety of regulations that need to be complied with. One of the key requirements is additional information to facilitate authentication across the chain of custody, using a combination of serialized labels and track and trace technology. (The subject of supply chain safety and security is discussed further in the next section.)

Regulators provide guidance and oversight to ensure the safe and secure production, packaging, storage, and distribution of life sciences products. However, the ultimate responsibility is on the marketing authorization holder.

6. Supply Chain Safety and Security

One of the major concerns for both life sciences industry regulatory bodies and customs and border protection agencies is the quality and efficacy of the drug materials and products that are manufactured and delivered to patients.

In addition to the complex environment for storage, distribution, and, ultimately, reimbursement, there are additional challenges for both pharmaceutical and biotech products. Increasing concerns related to counterfeiting, adulteration, and diversion have resulted in additional regulations that must be complied with.

EU Falsified Medicines Directive

Enacted in 2013, this directive introduced track and trace regulations to monitor and control the safety and supply of medicines for human use. Requirements include:

Serialization – manufacturers must mark packages with four data elements:

- Product identifier

- Serial number

- Lot or batch number

- Expiry date

Serialization should take place at the secondary or saleable unit to enable product verification across the chain of custody. By law, pharmacy dispensers must verify product identity prior to dispensing. Safety elements, to include tamper-evident packaging and labels, must also be verified.

Reporting - Reporting of product code, lot of batch, expiry date, doses per pack, target market, and serialization detail must be done to the European Medicines Verification System (EMVS) to verify identity of pharmaceutical products for sale in the EU. In some cases it is also necessary for supply chain partners to perform parallel reporting.

U.S. Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA)

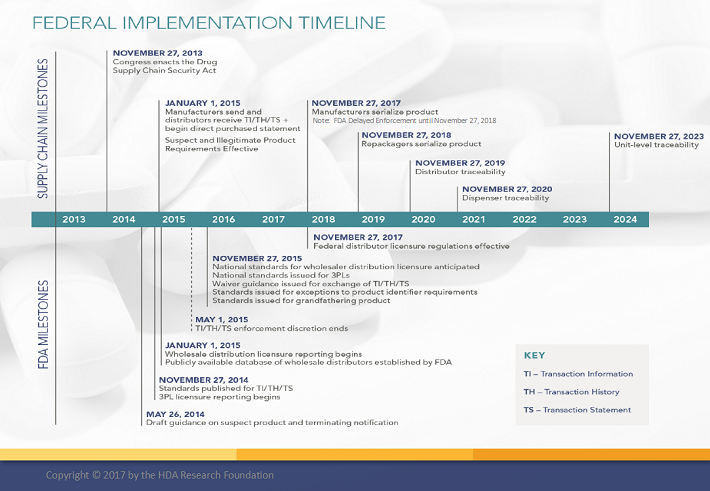

The DSCSA is Title II of the Drug Quality and Security Act (DQSA) that came into force in 2013. The DSCSA defines the implementation model for an interoperable electronic system to authenticate and track marketed prescription drugs in the U.S. By 2023, this will enable serialized traceability for individual packages across the commercial supply chain.

This information is required in three different levels of documentation

- Transaction information (TI):

- Name and identity of the drug product

- National Drug Code

- Product strength and dosage

- Container size and number of containers

- Batch number (from 2023 this should include a unit serial number)

- Transaction date (for shipment)

- Delivery date (if delivered more than 24 hours after transaction date)

- Name and address of entity to whom ownership is transferred

- Transaction history (TH)

Record of all transactions for movement of product, going back to the manufacturer, in paper or in electronic format

- Transaction statement (TS)

This is a paper or electronic declaration that the entity transferring ownership:

- Is authorized

- Has received the product from a licensed/authorized entity

- That the transaction data (TI) and TH obtained from a previous owner comply with regulations

- Is not knowingly the supplier of a suspicious of illegal product

- That systems and process used for verification are in compliance with regulations

- That no false transaction data was shared and that no transaction data has been changed

- All TI/TH/TS documentation must be retained for six years.

The following illustrates FDA regulation with an associated timeline.

7. Financial Models

As stated earlier, the flow of materials is related to the flow of cash and change of ownership across the extended chain of custody from shipment of product to delivery to final point of care. Supply chain-related events and associated transactions should be mapped out to identify specific triggers and information requirements across the overall distribution network.

Supply chain models should be developed to identify any risks, constraints, or areas of opportunity for the flow of cash in support of the order-to-cash cycle. It is recommended that this activity include a cross functional team of stakeholders and subject matter experts, to include, but not limited to:

- Finance

- Information technology

- Sales and marketing

- Legal

- Quality

- Supply chain and manufacturing operations

Further considerations for different ownership and distribution models should be evaluated, always ensuring that the key objectives of the business strategy are in alignment with these financial models.

8. Data Integrity and Control

There are many challenges in a multidimensional and multi-echelon supply chain, not the least of which is the exchange and retention of timely and accurate information. In common with the flow of goods and cash, the flow and sharing of both transactional and event-level data are key functions of an effective supply chain. From initiation of the shipment plan to each of the process steps across the chain of custody, there are incremental references and time stamps that should be captured, retained, and shared. Data sources, as well as the timeliness and accuracy of data, should be included in a detailed end-to-end process review. Although ideally the generation of data should be an automated process, the reality is that there will be a variety of data that is shared using EDI transaction-level files and event and exception data generated by data loggers and tracking devices, as well as data that is captured in the field using handheld devices, log books, or manual data entry.

Data integrity is an area of concern for regulators, and diligence in data management is critical.

In addition to the legacy systems within the ecosystem across the supply chain, there are specialized applications that are available to integrate data across the shipment and product life cycle. Known as orchestration platforms, these independent applications provide enhanced capabilities for command and control at the execution level — while capturing additional data points for operational analysis and review.

In Conclusion

The journey from discovery to commercialization can be long and filled with obstacles and challenges. However, by taking a structured approach to the development of a clearly defined supply chain and distribution strategy, the path toward the ultimate goal — the patient at the end of the supply chain — can be a clear one. Enjoy the journey.

Note: A big thank you to the HDA Research Foundation for sharing the illustrations used in this document.

About The Author:

Carla Reed is a seasoned supply chain professional with more than 25 years of experience providing leadership and program management across a variety of programs for the life sciences industry. Her broad range of experience and expertise has provided solutions for pharmaceutical and biotech companies challenged by the growing complexity of extended supply chain environments. Her firm, New Creed LLC, provides change leadership to facilitate sustainable solutions, providing hands-on experience in all aspects of supply chain operations. You can email her at carla@newcreed.com or connect with her on LinkedIn.

Carla Reed is a seasoned supply chain professional with more than 25 years of experience providing leadership and program management across a variety of programs for the life sciences industry. Her broad range of experience and expertise has provided solutions for pharmaceutical and biotech companies challenged by the growing complexity of extended supply chain environments. Her firm, New Creed LLC, provides change leadership to facilitate sustainable solutions, providing hands-on experience in all aspects of supply chain operations. You can email her at carla@newcreed.com or connect with her on LinkedIn.