A Hierarchy Of Metrics Brings Strategy Into Biopharma's Daily Work

By Irwin Hirsh, Q-Specialists AB

In an earlier article, Why Knowledge Workers Must Embrace Standard Work, I argued that structure doesn’t constrain thinking — it enables it. Standard work, when applied thoughtfully, reduces cognitive load and allows scientists and engineers to direct their energy toward higher-order reasoning, creativity, and problem solving. By organizing routine decisions, structure frees the mind to focus on what truly requires judgment.

In this context, critical thinking doesn’t mean endless analysis, it means the disciplined use of evidence, logic, and structured reasoning to guide action. It’s the scientific mindset applied to business: questioning assumptions, testing ideas, and distinguishing what is known from what is merely believed. The same logic applies at the organizational level. Across the biopharma value chain — from process development to manufacturing — businesses are flooded with data, decisions, and deadlines.

The pressure to move faster, driven by AI-assisted discovery, hampered by complex outsourcing networks, and exacerbated by accelerated regulatory pathways, magnifies this challenge. Information now flows faster than organizations can think about it, and without deliberate structure, decision-making becomes reactive rather than reflective. Teams are intelligent, motivated, and technically capable, yet the enterprise often struggles to convert effort into coherent progress.

The problem isn’t a lack of talent; it’s a lack of structure in how the organization thinks. Just as an individual without standard work becomes overwhelmed by unprioritized tasks, a business without structured reasoning becomes distracted by unprioritized goals.

This unstructured thinking shows up in subtle ways: analytical methods developed for compliance to ICH Q2 rather than longevity and deeper process knowledge, risk assessments completed for form rather than insight, performance metrics tracked for visibility rather than value.

For example, when an analytical method is designed merely to satisfy a validation milestone rather than to deepen process understanding, the short-term win becomes a long-term liability. The same pattern repeats in manufacturing when deviation data is trended without questioning whether the right variables are even being measured. Each decision may appear reasonable in isolation, but together they create a form of cognitive overload at the organizational scale — where activity replaces progress and local optimization undermines collective success.

A hierarchy of metrics offers a way out of this trap. It gives the organization a framework for structured reasoning — connecting strategy, operations, and learning through a visible chain of logic. Where standard work aligns how knowledge workers perform their tasks, a hierarchy of metrics aligns why the organization undertakes its tasks and how it measures their impact. In both cases, structure doesn’t replace critical thinking; it ensures it happens consistently and in the right direction.

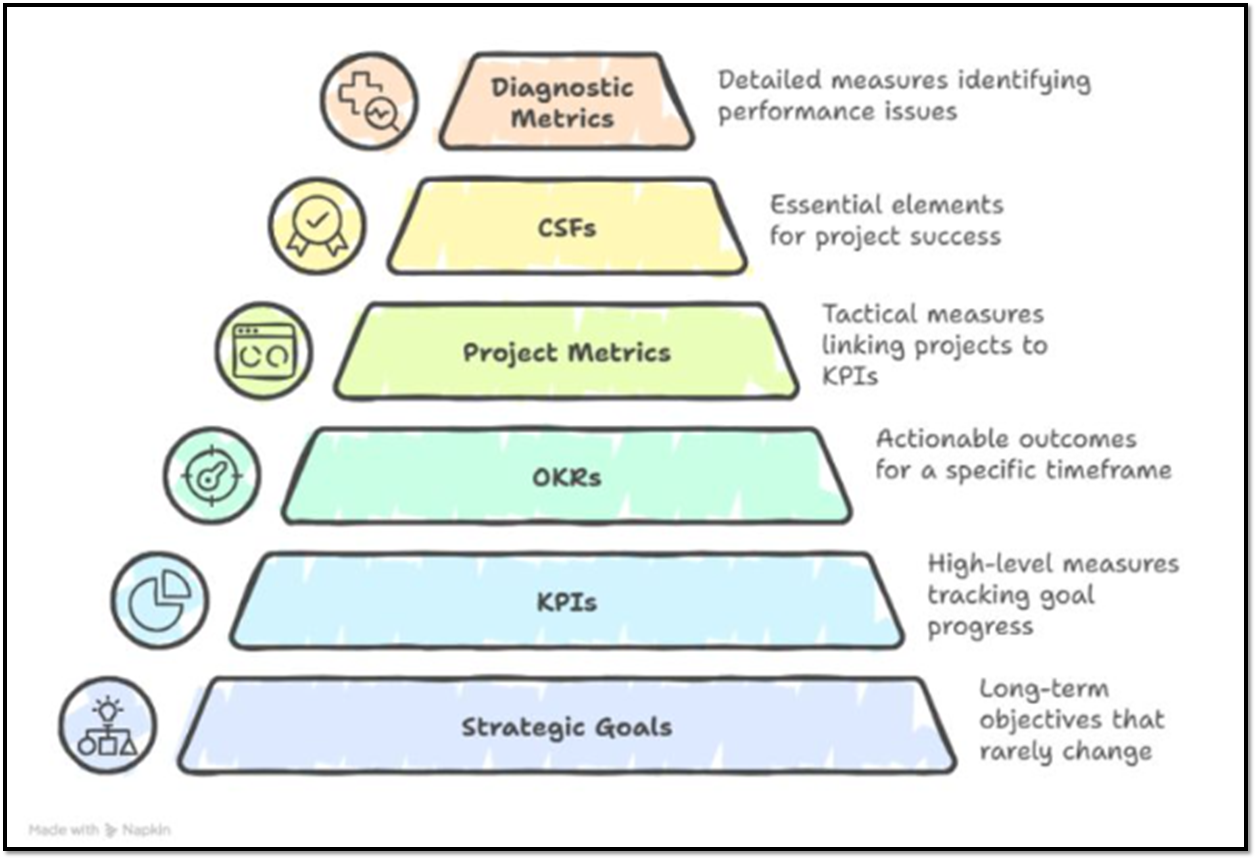

Source: Irwin Hirsh

Figure 1. Hierarchy of Metrics — a structured reasoning framework linking strategic goals to diagnostic insight.

At its core, a hierarchy of metrics organizes decision-making from purpose to practice:

- Strategic Goals — The enduring “why” of the business, such as patient impact, regulatory reliability, or commercial viability.

- Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) — High-level measures that show whether the organization is moving toward those goals.

- Objectives & Key Results (OKRs) — Translating intent into near-term, measurable outcomes for teams and functions.

- Project Metrics — Tactical measures linking project progress to those higher KPIs.

- Critical Success Factors (CSFs) — The “must-haves” that determine whether a project or process can succeed.

- Diagnostic Metrics — Detailed indicators that explain why performance is off-track — identifying the bottlenecks, variations, or inefficiencies behind the numbers.

The hierarchy ensures that what is measured at any level serves a defined purpose. Strategic goals and KPIs anchor direction; OKRs, project metrics, and diagnostics evolve with each phase of learning. This way, the business avoids the trap of measuring for measurement’s sake and instead creates a reasoning system where every number tells a story connected to value creation.

Yet, structure alone is not enough. A hierarchy of metrics may define how the business stands, but it will not hold if the people who do the work are excluded from its purpose. As Daniel Pink and others have shown, sustained engagement arises when individuals understand how their work contributes to a broader goal, have the autonomy and tools to act, and receive regular feedback that connects their results to the organization’s performance. The same holds true in biopharma: if metrics are not communicated, understood, and linked to daily decisions, they become silent — numbers on a dashboard rather than signals for coordinated action. For a hierarchy of metrics to succeed, it must not only structure the organization’s thinking but also activate it through shared understanding.

Ultimately, a hierarchy of metrics is not just a governance tool; it’s a discipline of thought. It transforms how an organization interprets complexity, separating genuine insight from the noise of activity. In biopharma, where the pace of development, regulatory pressure, and data volume are all accelerating, such discipline determines whether decisions advance strategy or simply sustain motion.

When structure and critical thinking work together, metrics become more than numbers; they become a common language connecting scientists, engineers, quality, and leadership. They align curiosity with purpose and give context to action thus ensuring that local optimizations strengthen, rather than fragment, the enterprise.

The next articles, as with the previous series, focus on knowledge management and will build on the foundational theme in the first article — critical thinking applied systematically. Again, the value chain, e.g., process development, manufacturing, analytical design, and technology transfer, will be explored.

In the end, business excellence in biopharma isn’t only about speed or compliance; it’s about cultivating the integrity of thought that keeps both on course.

About The Author:

Irwin Hirsh has 30 years of pharma experience with a background in CMC encompassing discovery, development, manufacturing, quality systems, QRM, and process validation. In 2008, Irwin joined Novo Nordisk, focusing on quality roles and spearheading initiatives related to QRM and life cycle approaches to validation. Subsequently, he transitioned to the Merck (DE) Healthcare division, where he held director roles within the biosimilars and biopharma business units. In 2018, he became a consultant concentrating on enhancing business efficiency and effectiveness. His primary focus involves building process-oriented systems within CMC and quality departments along with implementing digital tools for knowledge management and sharing.

Irwin Hirsh has 30 years of pharma experience with a background in CMC encompassing discovery, development, manufacturing, quality systems, QRM, and process validation. In 2008, Irwin joined Novo Nordisk, focusing on quality roles and spearheading initiatives related to QRM and life cycle approaches to validation. Subsequently, he transitioned to the Merck (DE) Healthcare division, where he held director roles within the biosimilars and biopharma business units. In 2018, he became a consultant concentrating on enhancing business efficiency and effectiveness. His primary focus involves building process-oriented systems within CMC and quality departments along with implementing digital tools for knowledge management and sharing.