What Does The U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement Mean For Biosimilars?

By Terri Stewart, senior advisor, Abraxeolus Consulting

The proposed text of the U.S.–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA) is intended to replace the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which has been in place since the mid-1990s. There have been some very strong reactions. Is the USMCA “an important step in bringing Mexico and Canada closer to high U.S. standards”1 or a crushing blow to patients that will “stifle biosimilar competition”2? As with most things, the details will matter, and of course the House and Senate must still approve the agreement. It’s important to consider 1) Whether the 10-year exclusivity impacts the filing of biosimilar applications, 2) What this change means in terms of the prioritization of some medicines from a public policy standpoint, and 3) The impact the agreement has on efforts to make biosimilars more accessible in the U.S.

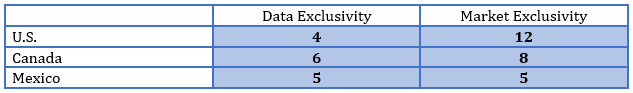

One of the details that is of particular importance is whether the agreement intends to set a minimum of 10 years of data exclusivity or market exclusivity for innovative biologics. Many analysts and industry experts have referred to the period of exclusivity in the proposed agreement text as data exclusivity, while others use the term market exclusivity. These terms are often used interchangeably, although in reality and in their timing of implications, they are not. The important difference is whether a biosimilar manufacturer can submit an application for review during that time period or not. If the term is meant to stop a health authority from approving a file for a period of time, leaving the market solely to the innovative product, then it should be referred to as a market exclusivity. If the term is meant to stop a health authority from referring to the scientific foundation of the innovative file and preventing submission of a file for review, then it should be referred to as a data exclusivity. In other words, market exclusivity affects launch date, whereas data exclusivity affects submission date.

As you can see from the chart below, the data exclusivity in each territory is far less than 10 years under current law. Any significant change to a biosimilar applicant’s ability to file a submission with their respective health authority could have significant downstream effects.

The plain text of Chapter 20 of the USMCA, indicates that the drafters intend “market protection” for “at least ten years from the date of first marketing approval.”3 I believe it would be a mistake to refer to this 10-year period as a data exclusivity, keeping in mind that the agreement represents only a minimum and implementation is key. The delta between the data exclusivity and the market exclusivity must be great enough to give a health authority the time necessary to review a submission. Otherwise, the market exclusivity is by default a longer term – in this case, 10 years plus administrative delay. It would benefit Canada and Mexico to keep this in mind, provided the agreement is ratified, and they move to implementation.

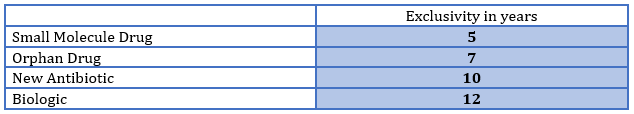

In BIO’s statement about the USMCA, they noted that the agreement “prioritize(s) biotechnology innovation.”4 On this point they are entirely correct. In the U.S., we have for some time now had a system of granting exclusivity that gives some therapies greater terms of exclusivity than others, and biologics have the longest period under current law. The chart below shows exclusivity in the U.S. by product type.

Note, for example, that an orphan drug gets two additional years of exclusivity compared to traditional small molecule drugs. This is due to the fact that orphan drugs treat rare medical conditions with patient populations under 200,000 and, due to their limited frequency of occurrence, offer little potential for profitability and returns on development risks and investment. And yet all biologics are given more than 60 percent longer exclusivity in the U.S., regardless of the population size, public health need, or effectiveness of the treatment. However, in Mexico and Canada, this distinction was not made. Previous to the USMCA, all innovative drugs were equal in terms of protection. This is a significant win for the innovative biologic industry. It has succeeded in expanding the view, beyond the U.S., that innovative biologics deserve prioritization.

The USMCA’s 10-year minimum market exclusivity is still under the 12 years granted in the U.S., so why is anyone upset about the agreement? While it’s true that there is no need for the U.S. to make legislative changes to comply, in this regard, the agreement changes the dynamics of the public policy debate on biosimilars. There are many that believe the existing exclusivity simply goes too far. In fact, President Obama regularly included in his budget proposals a decrease from 12 years to 7 years of market exclusivity for biologics. The current administration has made it clear that the biosimilars market is of utmost importance to combatting increasing drug prices. It has taken several actions to encourage the development and use of biosimilars.

The FDA often refers to the virtuous cycle of innovation and competition, in which manufacturers invest in new therapies, but after a time these therapies have competitors, prices are lower for patients, and in turn manufacturers continue to invest in the next new therapy. The lack of competition and the lengthy de facto market exclusivity for most biologics has many asking if the solution lies in changing the framework at home rather than encouraging other markets to match the U.S. And for these reasons, the agreement appears to be a setback for those that believe lengthy exclusivity is not necessary to encourage innovation and perhaps a departure for the administration from their otherwise pro-biosimilar policies.

It is too early to tell what effect the USMCA will have on the U.S. biosimilar market. Market exclusivity is only one of the myriad factors considered when commercializing a biosimilar medicine. We should take this opportunity to more broadly discuss the public policy motivations behind drug exclusivities. What factors should be included when determining their duration: the amount of investment required to invent a new therapy, the disease state that is being treated, the number of patients being treated, whether the therapy is curative, whether the therapy is a significant improvement to other existing therapies? And at what point is the cost of medicine so prohibitive to its use as to rebalance the factors that we have given weight? The importance of trade agreements is too often overlooked. These agreements serve as an opportunity for the U.S. to share with other territories the policy solutions that we have gotten right and adopt solutions that have been successful outside of the U.S. But did we actually get it right this time or should we be learning from Canada and/or Mexico instead? Should innovative biologics continue to be the highest priority regardless of rarity of disease, size of treatable population, or the significance of improvement over existing therapies?

References:

- BIO Statement on the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, October 4, 2018

- AAM Opposes Barriers to Generic Drug and Biosimilar Access in Proposed US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), October 1, 2018

- https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/agreements/FTA/USMCA/20%20Intellectual%20Property.pdf

- BIO Statement on the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, October 4, 2018

About The Author:

Terri Stewart is senior advisor of Abraxeolus Consulting. She offers problem solving leadership and expertise in healthcare in areas such as government affairs, regulations, policy, and their direct implications for a pharmaceutical firm’s operations. Stewart has had extensive interaction with Congress, federal agencies, trade associations, and healthcare industry leaders with the proven ability to drive consensus. Previous roles include VP of global regulatory intelligence, policy, and compliance for Teva Pharmaceuticals and lead federal lobbyist for Barr Laboratories. She holds a degree in government affairs from George Mason University and a J.D. from Catholic University’s Columbus School of Law. You can reach her at Terri.Stewart@abraxeolus.com or connect with her on LinkedIn.

Terri Stewart is senior advisor of Abraxeolus Consulting. She offers problem solving leadership and expertise in healthcare in areas such as government affairs, regulations, policy, and their direct implications for a pharmaceutical firm’s operations. Stewart has had extensive interaction with Congress, federal agencies, trade associations, and healthcare industry leaders with the proven ability to drive consensus. Previous roles include VP of global regulatory intelligence, policy, and compliance for Teva Pharmaceuticals and lead federal lobbyist for Barr Laboratories. She holds a degree in government affairs from George Mason University and a J.D. from Catholic University’s Columbus School of Law. You can reach her at Terri.Stewart@abraxeolus.com or connect with her on LinkedIn.