Frequent Deficiencies In GMP Inspections, Part 1

By Lea Joos, The Government of Upper Bavaria

If a film were made on GMP inspections, it could be titled GMP Inspections Feel like Groundhog Day. It is sometimes almost astonishing how often companies "commit" similar or even the same mistakes — in (almost) always the same places. Some countries, e.g., the U.K. and Brazil, publish deficiency statistics at irregular intervals, e.g., MHRA GMP Deficiency Data 20191 or Quality of medicines: Deficiencies found by Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (ANVISA) on good manufacturing practices international inspections.2

But what do such statistics actually say? Do they really reflect the areas where companies are making the most or most serious mistakes, as indicated in the MHRA introduction? Or do they perhaps rather reflect the priorities of the respective authorities? Or perhaps also the most recent regulatory changes?

Presumably, the statistical findings result from a mixture of all these influencing variables. The informative value of such statistics is therefore limited and in some cases quickly becomes outdated again. Could such statistics help in carrying out self-inspections or evaluating possibilities for improvement in order to avoid exactly this impression of "always the same defects"? It's possible. But the pitfalls are not only in the ignorance of the mistakes of others, as will be shown in the following examples from GMP inspection practice.

Inadequate Handling Of Deviations

The deficiency: In the case of the deviation inspected, it was found that the batch number, which had to be manually transferred to the product before production started, was not correctly transferred to the product. The cause was found to be a "human error" in the manual transfer of the batch number during the root cause analysis. An evaluation of possible technical or organizational causes for the "human error" was missing. The evaluation was also missing for the third deviation of this type in the last three months. (Ref.: EU GMP Guide Part I No. 1.4 xiv)

What Was The Problem?

The faulty transfer of the batch number before the start of production was attributed to a human factor without a more detailed analysis of the cause. Due to the manual transfer, the cause "human error" was obvious: an employee had obviously transferred the batch number incorrectly. However, according to EU GMP Guide Part I No. 1.4 xiv, so-called "human error" should be handled very carefully and should only be recorded as the cause if other technical, process-related, system-related, or organizational causes could be excluded.

The extent to which the transfer error was due to other causes of a technical or organizational nature was not verified by the company in the present case. The "correctness" of the assumed cause was not checked even after the third deviation of this type within the last three months. For each of these deviations, human error was found to be the cause. As a preventive measure, the employee concerned was given follow-up training.

At the least, however, a recurrence of a deviation should lead to questioning of an initially identified cause. If one employee makes the same mistake again and again or several employees make the same mistake, the causes may actually lie in the process or in the process flow.

This Is The Most Common Pitfall

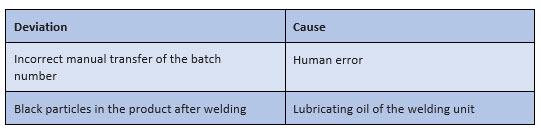

For the practical implementation of the root cause analysis, the instructions of the companies often do not contain sufficient specifications – except that the "most probable" cause must be identified. Subjectively, the most probable cause can sometimes be found very quickly, as shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1: Possible "snapshots" for a root cause analysis in the context of processing a deviation

However, such "snapshots" are initially only subjective assumptions – even if they usually do not come from one person alone. They must be further questioned, checked, and verified.

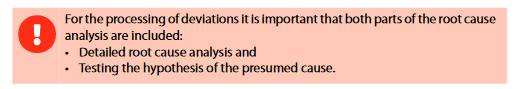

To Avoid This Error

There are several methods that can be used to analyze the cause of a deviation. However, it does not always require elaborate diagrams to penetrate to the necessary depth within the framework of a root cause analysis.

When analyzing the causes, imagine that you have an inquisitive child next to you who keeps bugging you with the question "why?“:

- Child: "Why did the employee transfer the batch number incorrectly?"

- You: "Because the employee could hardly recognize the batch number on the instruction document."

- Child: "Why could the employee hardly recognize the batch number on the instruction document?"

- You: "Because the instruction document can only be on the side table at the time of transfer and is therefore relatively far away from the employee.“

- Child: "Why is the document so far away?"

- You: "Because the instruction documents cannot be placed on the work table for reasons of hygiene."

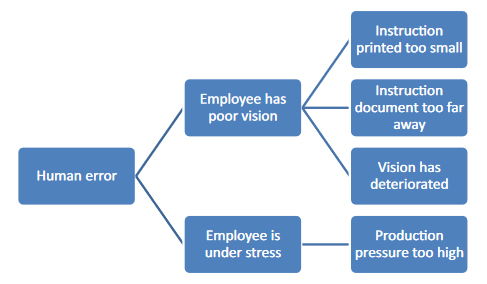

With this "child's play" questioning method, you can get closer to the actual cause relatively easily, as shown once again in Figure 2.

Figure 2: "Child's play" cause analysis using "why" questions. Each connecting stroke stands for a "why" question.

After the fifth "why?" you may be very annoyed by your child's questions, but you are much closer to identifying the most likely cause: You may have noticed that the deviation could have been caused by an unfavorable work routine. But even this is still a guess and has to be verified by checking, depending on the type and severity of the deviation. In this case, the possibilities of such verification are limited, since only the employees can be questioned or the effectiveness of previous corrective and preventive measures can be verified.

The second example in Figure 1 also needs to be checked. Let's say that during the root cause analysis of the particulate contamination of your product, you have "determined" by asking why, that the cause is most likely lubricating oil from the welding equipment. Then you should substantiate this assumption by analyzing the contamination – and hopefully determine that it is lubricating oil. If it is not lubricating oil, a large-scale search may be necessary to analyze the nature and origin of the particles.

Root cause analysis can also work in this direction: First of all, a thorough examination is carried out and then the why questions are asked. This means that you first find out that there are complexes of degradation product and active ingredient – and then you ask yourself where and why these complexes arise. However, this approach places much greater demands on the analytics. It is much more difficult to determine the physico-chemical-microbiological nature of an unknown impurity than it is to determine whether it is a lubricating oil or not.

Only when you have found the most likely cause of the deviation can you take effective action. Using the example of the transfer of the wrong batch number, this means: If you find out that the transfer of the wrong batch number is caused by the fact that the instruction document is too far away from the transferring employee, you can reorganize the workflow and place the instruction document in a different, more visible location to make it easier for employees to transfer the batch number manually.

If you generally assume "human error" as the most probable cause and derive the employee's retraining from this, they or another employee will make the mistake again. The same is true if you identify a wrong cause: If you come to the conclusion during the root cause analysis that the employee's vision is impaired and you advise the employee to see an ophthalmologist, the error will probably occur again as long as the specification document is too far away and cannot be seen easily.

Inadequate Handling Of Changes

The deficiency: The change management procedure specified that changes had to be approved before implementation. In accordance with the procedural instructions, a so-called Change Control Committee (CC Committee) should be convened for a decision. The exact composition of this CC Committee was not specified. According to company information, the composition varied depending on the change request. It was therefore unclear how to ensure that the necessary persons were involved, e.g., Qualified Person, Head of Production, or responsible person for wholesale distribution. Furthermore, the implementation of the measures defined by the CC Committee could not be traced from the change documentation viewed, although the change request had already been completed at the time of the inspection. An inspection of the effectiveness of the change was also missing. (Ref.: EU GMP Guide Part I No. 1.4 xii, xiii and Annex 15 No. 11.5 and 11.7)

What Was The Problem?

The concrete involvement of the persons possibly required for the approval was not comprehensible from the specifications of the procedural instructions. The procedural instructions merely stipulated that a so-called "CC Committee" would decide on the approval of a change. Depending on the change, however, the involvement of the respective legally responsible person(s) must be evident from the documentation. How this involvement is ensured was not apparent from the established procedure.

Necessary measures had been determined by the CC Committee in the course of the change request. In some cases, measures had been defined whose implementation would take some time, such as changing a delimitation of responsibility contract. Due to the long-term nature of the measures, the implementation of the measures was not tracked and the change request was nevertheless already closed. Accordingly, the effectiveness of the implemented change with regard to the (quality) objectives to be achieved was not documented in the change request.

This Is The Most Common Pitfall

The change control system is usually a cross-company system that records all GMP-relevant changes. The range of changes is correspondingly large.

Many companies have therefore implemented a committee, such as the so-called CC Committee, for approval. The members of such a CC Committee should normally consist of the head of quality assurance, the qualified person, the heads of production and quality control, the qualified person for pharmacovigilance, the information officer, and the heads of sales and regulatory affairs.

However, this is often not unchangeably fixed but varies in practice depending on the area affected by the change. From a company's point of view, this can make sense, since every involvement of a (management) person always ties up their capacities.

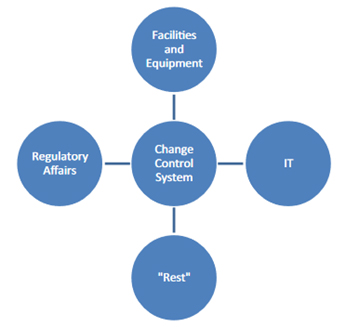

Therefore, as shown in Figure 3 some companies sometimes split into "different" change systems:

Figure 3: Frequent "splitting" of the change control system by companies

Such a division can help to define responsibilities more clearly and unalterably. However, such a split also carries the danger of implementing different parallel systems that develop separately. Such parallel systems can make it difficult for employees to find their way around. They also can be sources of error, for example, if changes to the temperature loggers that are processed in the "equipment" area of responsibility are subject to different regulations than changes to the associated monitoring software, which fall under the IT area.

The aim should therefore be to establish a uniform change control system wherever possible, while still clearly defining responsibilities. This particularly concerns the involvement of legally responsible persons in the evaluation and approval of change requests.

The implementation of measures is sometimes not fully tracked because long-term measures in particular cannot be processed in a timely manner: The outstanding change requests would pile up on the desk. This would create "dead files," so to speak, whose monitoring would tie up staff capacities that are often needed more urgently elsewhere.

To Avoid This Error

How can you ensure that all relevant people are involved?

- One possibility is to involve all relevant people in each change request, e.g., the head of quality control in the case of a production-related change request. However, this means a great deal more work for all employees.

- The other option is to designate specific people for the assessment and approval of change requests, e.g., qualified person and/or quality assurance officer. These individuals define the further scope of the respective change request in writing and thus include the necessary persons in the evaluation and approval.

And between these two "borderline positions," other variants can be established that make use of both models. For example, a core team could be established, over whose desk every change has to go and who then call in other people as necessary.

How Can Measures From Change Requests Be Tracked And Their Effectiveness Checked?

The documentation of the implementation of necessary measures should in any case be made within the framework of the change request. This also applies to long-term measures. Otherwise, the change request lacks a control – first, of the implementation of necessary measures and, second, of the effectiveness of the measures. Even if a change request could be "open" for a very long time in such a case, the change request can only be completed after all measures have been implemented and the effectiveness has been checked. Only then is the change request successfully implemented.

In order to avoid excessive delays, it should be decided in the context of each change request what deadlines are to be set for the implementation of the measure concerned. These should be followed up accordingly. If the deadlines cannot be met, this should be documented and evaluated accordingly.

If necessary, an electronic system can help to manage the change requests. Such systems can, for example, "immobilize" a change request for a certain period of time in order to reactivate it at the predetermined implementation deadline of the agreed measure. This can help to monitor implementation. Of course, comparable systems can also be paper-based, but those are usually more complex.

This article is an excerpt from GMP knowledge contained in the online portal GMP Compliance Adviser, which provides in-depth information about GMP best practices and regulations with a focus on Europe, but also referring to USA, Japan, and many more (PIC/S, ICH, WHO, etc.).

References

- https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/good-manufacturing-practice-inspection-deficiencies

- Quality of medicines: Deficiencies found by Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (ANVISA) on good manufacturing practices international inspections, PLoS One, 2018; 13(8): e0202084 (https://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6082550/)

About The Author:

Lea Joos has worked as a GMP inspector for the government of Upper Bavaria since 2012. Her tasks include the monitoring of GMP and GDP operations as well as tissue facilities for pharma companies. After studying pharmacy, Joos initially worked as a research assistant at the Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich. In 2012, she began her career with the authorities. Since 2015, she also has acted as a speaker on GMP and GDP topics. She can be reached at lea.joos@gmx.de.

Lea Joos has worked as a GMP inspector for the government of Upper Bavaria since 2012. Her tasks include the monitoring of GMP and GDP operations as well as tissue facilities for pharma companies. After studying pharmacy, Joos initially worked as a research assistant at the Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich. In 2012, she began her career with the authorities. Since 2015, she also has acted as a speaker on GMP and GDP topics. She can be reached at lea.joos@gmx.de.