Biologics Pricing: A Deep-Dive Into Dynamics And Behaviors Over Time

By Edric Engert, managing director, Abraxeolus Consulting

In the article “Do The Arguments For Pharmaceutical Price Increases Make Sense?”, we began to look comprehensively at the U.S. healthcare system from a cost perspective. In it, we acknowledged and illustrated that there is no single reason behind the outpacing of inflation and GDP growth by healthcare spending and healthcare pricing. We then focused on the pharmaceutical industry, advancing data-driven arguments for how the risk of developing and obtaining approval of pharmaceutical products neither supports nor excuses the pricing of drugs we have seen in the United States.

In this second part of the series, we’ll continue our investigation by diving into some of the details and datasets behind pharmaceutical pricing, trends, and behaviors over time. We hope it will better drive the discussion forward, finding a path for more effective cost management and economic sustainability of U.S. pharmaceutical spending while maintaining the drive for innovation.

Let us begin by looking at some data and understanding the dynamics and behaviors over time. There are many forms that the word “pricing” can take, from wholesale acquisition cost (WAC), average manufacturer price (AMP), average selling price (ASP), and average wholesale price (AWP), to federal ceiling price (FCP), non-federal average manufacturer price (non-FAMP), 340(b) drug discount program, and Medicare payment limit.

For this discussion, let’s start with WAC, which can be thought of as a list price and the charge to wholesalers and specialty distributors. It doesn’t include price concessions offered in the market (such as prompt pay discounts), but these are typically no more than just a few percentage points, so WAC is a good overall indicator of pricing from manufacturer to the channels.

Let’s continue by looking first at the high prices of pharmaceuticals in the U.S. at launch. Just a few examples of WAC per unit for illustration are:

- Humira pediatric – $3,654.03

- Humira pen – $4,872.04

- Cimzia – $1,315.68

- Stelara – $9,326.00

Some claim this is simply due to the specialized nature of the product and the risk associated with such products. The risk argument has already been debunked in part one of this series, so let’s look at comparators in other markets to understand the true nature of “high” in “high prices.”

- Humira costs more by 96 percent in the U.S. than in the U.K. and more by 225 percent than in Switzerland. (healthsystemtracker.org)

- Avastin, another well-known biologic, is 124 percent higher in the U.S. than in Switzerland and 736% higher than in the U.K. (healthsystemtracker.org)

- This asymmetry of pricing is not restricted to novel biologics and, hence, specialty products. Xarelto, a small molecule treatment for blood clots and deep vein thrombosis, is 131 percent higher in the U.S. than in the U.K. and 186 percent more than in Switzerland. (healthsystemtracker.org)

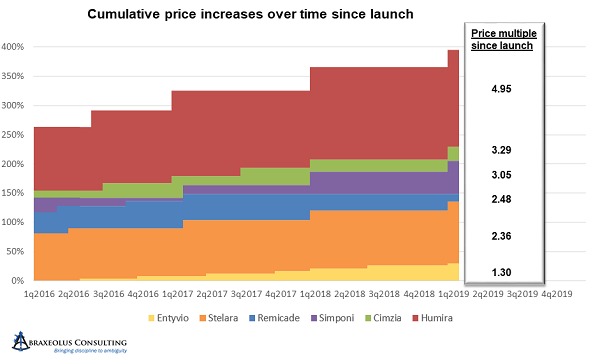

And it doesn’t end with high launch prices. Prices can also increase significantly over time. At Abraxeolus, we took a set of products that covered an entire therapeutic area, all in the novel biologics space, and we reviewed their WAC pricing from launch until the measurement period (spring 2019). What we found was that the WAC increased on average, every year, to the tune of 11.4 percent. There were no product advancements or enhancements, simply price increases for the same product.

To make sure that we weren’t being fooled by the impact of an outlier here or there, we looked at the minimum and the maximum price increases in the set of products reviewed. The minimum was an average price increase, each year after launch, of 5.3 percent. The maximum went all the way to 16.7 percent.

Even ASP per unit, after all the markups between manufacturer and payor, went up on average 8.9 percent year after year for the same products.

As you can see from the averages, maximums, and minimums, not all pricing behaviors across all products are inflating over time to the same degree. It is a systemic issue that must be addressed, but the severity depends on the player.

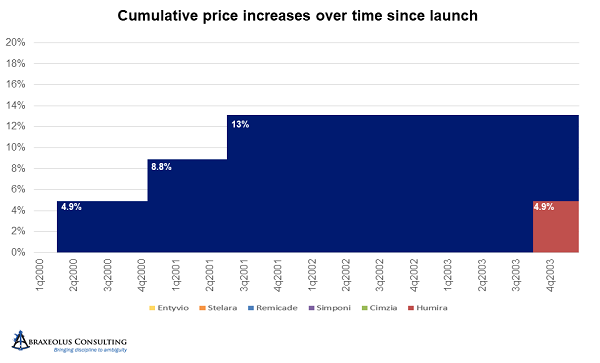

Janssen’s Remicade is a great example of this. Janssen took price hikes every eight months for three turns after launch, bringing the price per unit up in aggregate to 13 percent higher than the launch price. It then deferred another price hike for four and a half years.

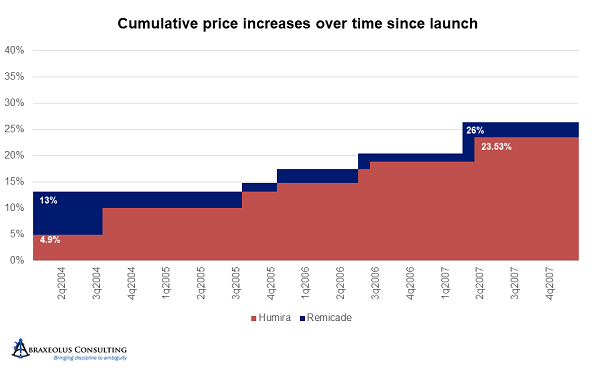

Unfortunately, during that four-and-a-half-year period, AbbVie launched Humira and took price hikes every year. AbbVie thereby became the price leader and started accelerating price hikes to every 10 months and at higher percentages than Janssen’s. After being on the market for only four years, and about four years after the launch of Remicade, by the end of 2007, AbbVie had taken price hikes that when aggregated nearly equaled those of Remicade. In other words, AbbVie raised prices in four years by an amount that took Janssen eight years to achieve, and at that point, Janssen was following AbbVie and no longer deferring price hikes.

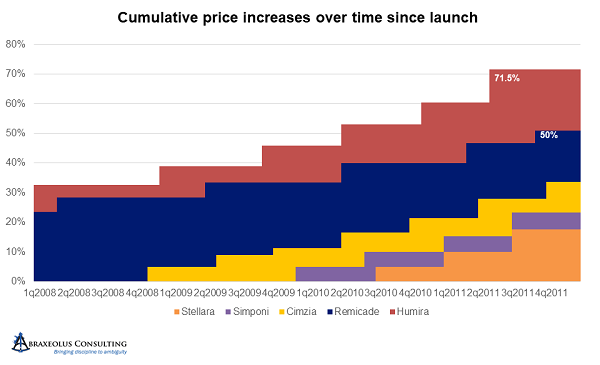

After 2007 and 2008, with UCB having recently launched Cimzia, AbbVie accelerated its price hikes even further to every six months, with all others following suit. Simponi and Stelara followed soon thereafter. The size of increases in each turn also increased, with only Janssen staying below 5 percent at 4.9 percent. By the end of 2011, Humira was already 70 percent above its launch price.

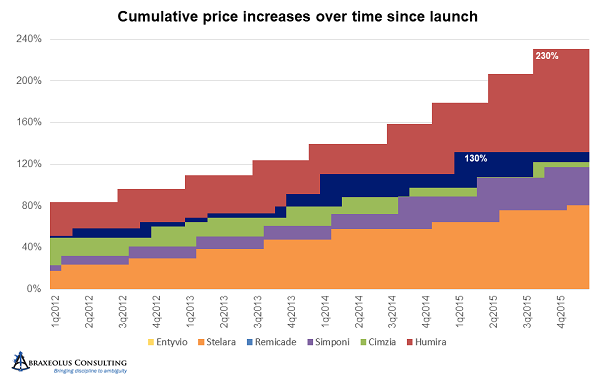

Between 2012 and 2015, AbbVie accelerated the pricing cycle yet again, moving from every six months to every five months, while simultaneously moving first to 7.9 percent increases then to 9.9 percent increases.

Janssen and UBC stayed with the six-month pricing cycle, with Janssen holding Remicade at 4.9 percent increases per turn. Simponi and Stelara were more aggressive but stayed below AbbVie’s Humira at 6.9 percent increases per turn. Cimzia was more erratic in its pricing, sometimes increasing prices 4.4 percent and other times going as high as 13.5 percent, with the majority at or above 9.9 percent.

By the end of 2015, all had taken significant and concerted pricing increases, with Humira at 240 percent higher – 3.4 times its original price – with the much later entrant Cimzia already 2.2 times its original price.

From 2016 onward, likely due to the focus that pharmaceutical pricing was finally receiving in Washington, everyone returned to annual price hikes and in greater moderation, at least relatively speaking, in the range of 6 to 7 percent. But by early 2019, Simponi was 3.05 times its launch price, Cimzia was 3.29 times launch price, and AbbVie’s Humira was 4.95 times launch price.

Janssen’s Remicade, on the other hand, while still being 2.48 times its launch price, clearly had experienced much more moderate price increases over time. It’s also worth noting that it has been on the market four years longer than Humira, eight years longer than Cimzia, and nine years longer than Simponi, making the disparity between accumulated price increases that much more impressive and noteworthy.

The Path Forward

The path forward, whatever we choose, must ensure economic sustainability of the system while stimulating innovation. Biosimilars will certainly play a key role in this. Of course, they will save the system money, but one must also concede that losses of exclusivity and, hence, biosimilars, greatly stimulate more innovation as well. How motivated would we be, after all, to bring new products to market if we can hold on to a current product’s exclusivity ad infinitum while raising prices every year? I have personally seen in corporate environments how the complacency can set in when a single product is “rolling in the dough” and appears to have little competition in the immediate future.

There are, unfortunately, many levers that need to be pulled regarding the obstacles to current biosimilar launches and adoption in the U.S. It’s not about continually claiming how much it could save us and asking why people won’t wake up to the obvious economics of the argument. The problem is in the processes, systems, and incentives in place to block their adoption. The problems include:

- Patent thickets

- Misinformation

- Bundling approaches to price negotiations and biosimilar adoption, and

- Key healthcare stakeholders immune to high costs and even benefiting from them

However, it’s important to note that the problem lies at launch and between launch and loss of exclusivity (LoE). The problem, and the potential solution, is not just after LoE and what kind of cost savings can be captured then. The result is that biosimilars, while necessary, are not sufficient.

Note that some moves to address the pre-LoE issue may put the biosimilar industry in danger, depending on how deep and severe they are. Some could greatly lower the financial incentives, making at-risk development of biosimilars a less tenable option. A comprehensive analysis including both pre- and post-LoE solutions working in tandem is therefore needed.

The most important next step is perhaps to look beyond product-by-product challenges and view the novel biologics industry and biosimilars industry as a whole. We should be looking at systemic issues and how to solve them systemically. What can we learn from other countries? Where and how have they succeeded? Where have they failed? And, finally, how could such learnings be applied in a tangible and actionable way to the U.S. healthcare market? The balanced objective, after all, is to continue to innovate, with continual innovation and product development driving value creation, not inflated pricing at launch, egregious price hikes year over year, and the resulting subsidization of healthcare for the whole world on the backs of America’s consumers and patients.

About The Author:

Edric Engert is managing director of Abraxeolus Consulting and has over 20 years of experience in the healthcare industry. He offers problem solving leadership and expertise in such areas as strategy and its operationalization; business development/in-licensing; portfolio strategy, selection, and management; operational improvement programs and turnarounds; and M&A. He has advised clients in such industries as biosimilars, generics, branded pharmaceuticals, API, healthcare information exchanges, medical supply, distributors, trade associations, and not-for-profit agencies. Prior roles included head of the biosimilars business at Teva, global head of portfolio management and in-licensing for Teva’s generics business, and global head of portfolio management and in-licensing at Sandoz, among others. Engert holds an MBA from Wharton and a BS in Mathematics from MIT.

Edric Engert is managing director of Abraxeolus Consulting and has over 20 years of experience in the healthcare industry. He offers problem solving leadership and expertise in such areas as strategy and its operationalization; business development/in-licensing; portfolio strategy, selection, and management; operational improvement programs and turnarounds; and M&A. He has advised clients in such industries as biosimilars, generics, branded pharmaceuticals, API, healthcare information exchanges, medical supply, distributors, trade associations, and not-for-profit agencies. Prior roles included head of the biosimilars business at Teva, global head of portfolio management and in-licensing for Teva’s generics business, and global head of portfolio management and in-licensing at Sandoz, among others. Engert holds an MBA from Wharton and a BS in Mathematics from MIT.