Are You The Weak Link In Your Own Pharma/Biotech Supply Chain? How To Find Out — And Fix It

By Marla Phillips, Ph.D., Xavier Health

A team composed of nearly 70 FDA, pharma/biotech, and medical device leaders — spanning 39 organizations and five countries — have concluded that companies trying to get a handle on issues in their supply chains should focus less on their suppliers and more on themselves as the possible source of the problems.

In a previous article, I described the work that led to the paradigm shift from a focus on suppliers to an internal focus, along with the rationale that led to the shift, which includes:

- Product and process knowledge: We lack enough understanding of our own product and process to know what we truly need from our suppliers.

- Supply chain development: We circumvent our own systems when developing our supply chain and do not engage our suppliers as subject matter experts.

- Supply chain management: We do not behave as trusted partners in our supplier relationships and do not respect the business of our suppliers.

The team has since completed a Good Supply Practices (GSPs) white paper using a methodical supply-by-design process that increases the reliability of incoming supply and therefore reduces the risk to finished product quality, patient safety, and business success. The GSPs complement the existing good practices suite that includes good manufacturing, distribution, clinical and laboratory practices (GMP, GDP, GCP, and GLP). They also provide a set of tools and methodologies that can be used to evaluate and mitigate product, material, supplier, and company risks.

Leverage Suppliers’ Expertise

While many life science product manufacturers have supplier selection and approval processes, most firms fail to leverage their suppliers’ knowledge about their products.

Often the company cross-functional teams are not teams, and they are not aligning. They simply work through functional hand-offs in their own silos and approach suppliers separately to discuss their own requirements.

Suppliers told the team that “more than half the time” it is important for them to know the intended use of their material to ensure it is appropriate for that use. Additionally, suppliers can share with the customer if there is material that has been developed in the past five years that they might not be aware of that performs better at the same cost.

Suppliers can have input on specifications if the intended use is known. Maybe the specification you request is way too tight, but there is no need for it to be so. It will just result in increased cost and a lot of waste. Perhaps a material you are using is seasonal — it performs one way when produced during a wet season and another way during a dry season. but it will still meet your spec regardless. This is especially common with mined excipients, whose properties also vary by the location where they are mined.

Suppliers have a great deal of knowledge they can share, but we aren’t even leveraging them as subject matter experts on their own materials.

Map Relationships For Risk

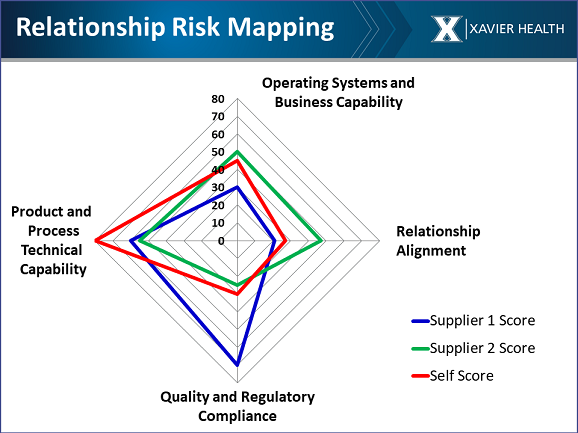

The Xavier supply chain team has created a tool through which companies can overlay the strengths and weaknesses of an existing or potential supplier with those of its own operations across four categories of risk, in order to identify the best partners for their supply chain. The four categories are: (1) operating systems and business capability, (2) relationship alignment, (3) quality and regulatory compliance systems, and (4) product and process technical capability.

The goals of this process, known as relationship risk mapping, are to:

- Choose the supplier that best meets the supply chain needs of the company, through an informed decision-making process

- Monitor the relationship performance of existing suppliers

- Identify supply chain partners that offset the weaknesses of the company, and partnerships in which the company can offset the weaknesses of the supplier

- Establish appropriate mitigating actions that address the true root cause of each risk for each relationship.

Instructions on how to create a relationship risk map and associated templates are included in an appendix to the white paper. You can go through the four categories and decide what is important to all of your cross-functional groups. Then, you can compare potential suppliers against the categories deemed most important.

Using the templates, the scores for the company self-assessment and for a short list of suppliers can be plotted on a radar chart. The resulting diagram can then be used to make an informed decision on which is the right supplier for your needs. Following is an example of a completed relationship risk map that one of the participating companies developed comparing two of its suppliers:

Note that Supplier 1 (shown in blue) performed well in the company’s quality and regulatory audits, whereas Supplier 2 (green) did not. Based only on that criterion, you historically would select Supplier 1. But if you look at operating systems and business capability, Supplier 1’s score indicates that it does not have current or future capacity and doesn’t manage its inventory well.

The relationship alignment score includes willingness to sign quality agreements and providing contacts who are knowledgeable, can service as your representative, and have the authority to make decisions. Supplier 1 scored very low in this area. They might be compliant, but without relationship alignment, you will be banging your head against the wall because you cannot get them to cooperate.

Supplier 2 may have not been chosen because they performed poorly in the quality audit, but they can keep you on the market, have phenomenal relationship alignment, and have good process and product technical capability.

If it is critical to you that your supplier has good compliance, and you are in a position such that you can invest in a supplier’s capacity — for example, by paying for an additional manufacturing line — you could propose that to Supplier 1. In this case it is an intentional decision, and you know what you are getting into.

Supplier 2, in this example, is a university. Frequently, universities don’t know much about GMPs, but they have developed a needed technology. It could be a bio-reagent — something that is very complicated to manufacture or develop. In this case, you could work with them to train them on GMPs and quality systems, and maybe put a person in the plant to observe and bring them up to speed. Alternatively, you may decide it’s better to purchase the technology and manufacture the product yourself.

Using these scenarios can help you choose the right supplier, even though at the outset it may look like neither would be a good fit. The GSP tools provide the level of granularity necessary to make informed decisions.

Where To Start?

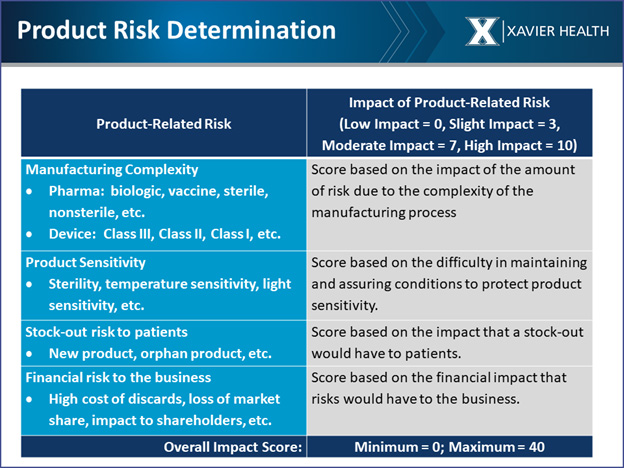

For large companies with thousands of suppliers, it can be a challenge determining which suppliers to start the supply chain assessment with. To help prioritize suppliers, the team developed a supply chain risk management triage process that evaluates product, material, and supplier risk. It suggests starting with supplier risk, dividing potential suppliers into high-, medium- and low-risk categories. Supplier risk looks at manufacturing complexity, product sensitivity, stock-out risk to patients, and financial risk to the business (see below).

These are examples of factors to consider in your risk-based decision-making process. You may choose to use other factors that you deem important, but the overall approach should view product risk more broadly.

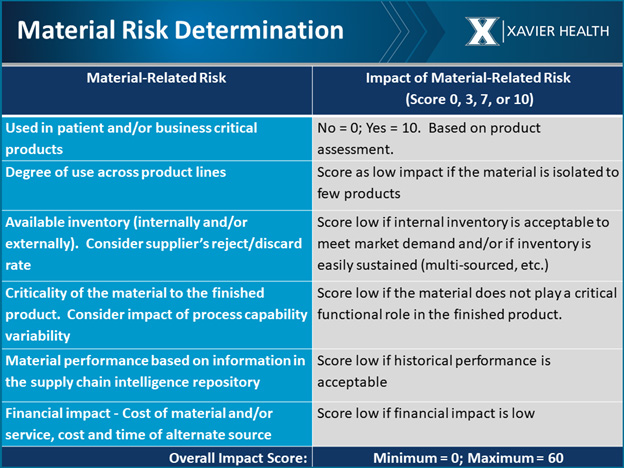

After determining the level of product risk, the risk of materials used to make the product should be examined. Materials are also ranked as high, medium, or low risk (see below).

For example, is the material used in patient- and/or business-critical products? That should be taken into consideration along with the use across product lines. If it is fairly low risk but used in every one of your products, it is considered a high-volume material. If something happens to that material, your entire business will be at risk.

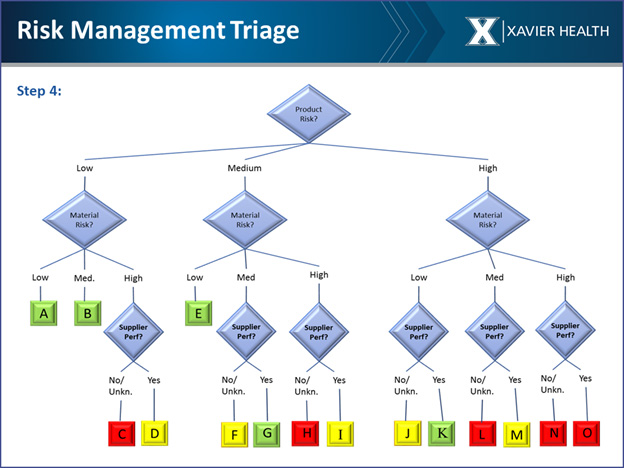

Once risk of the material is determined, the next step is looking at the supplier risk. When all of the supplier risk information is pulled together, it can be mapped using red, yellow, and green to visualize the overall risk (see below).

The team has also developed an automatic risk elevation process that is described in the GSP white paper, showing how to determine risk that would not be caught using the triage process.

Consider a scenario in which a company supplies many different materials, but none is considered high volume, and no specific material cuts across numerous product lines. If something significant happens to that supplier — for example, a compliance, financial, or facility issue — a large number of your products will be at risk. This example illustrates why it is important to develop cross-functional teams that can identify other scenarios that may arise within your supply chain.

As a first step, the GSP team recommends mapping your supply chains. Know your suppliers and their suppliers. Conduct risk assessments. Start using the GSPs in a way that makes sense for your business and is commensurate with your needs.

Next, consider forming a cross-functional team that will be used for all future activities in the supply chain area. Or use the supplier requirements tool to decide what is most important to your company. Use it the next time the company changes a supplier. You could also begin by developing a communication strategy or conducting a self-qualification. Pick a place to start, demonstrate some ROI, and then start folding in the other pieces.

Next Steps

The GSP white paper is currently available through Xavier Health. The paper is 86 pages, with 17 appendices comprising an additional 71 pages. It is being recognized as a global tool for industry and regulators.

Xavier Health is working with entities, such as NSF International — a standard-setting group accredited by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) — to convert the white paper into a publicly available standard. The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) will be converting portions of the GSP work into a general chapter above 1000.

The GSPs may also be added to the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) supply chain security toolkit, which was created in an effort spearheaded by the FDA “to maximize available global resources and to deliver quality trainings and best practices and for securing the global supply chain for medical products.” Additional work needs to be done on the APEC change management process before the white paper can be considered. The APEC effort is being led by FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) Office of Compliance Deputy Director Ilisa Bernstein.

The GSP team has also been approached by regulators asking for the tools so they could be used during inspections to increase the areas of supply chain management that can be investigated on inspection.

To download a free copy of Good Supply Practices for the 21st Century, click here. Name, title, company name, address and email address are required to download.

A one-day workshop on the GSP white paper and how your company can best use it will be held at Xavier University on March 12, the day before the FDA/Xavier PharmaLink conference. The PharmaLink conference will include an interactive session titled, “How Qualified Are You to be Part of Your Own Supply Chain?” An additional one-day GSP workshop will be held on April 30, the day before the FDA/Xavier MedCon conference for the medical device community.

About The Author:

Marla A. Phillips, Ph.D., joined Xavier University in 2008 as the director of Xavier Health, where she leads initiatives with FDA officials and pharmaceutical and medical device professionals. Phillips began working in the pharmaceutical industry for Merck in 1996, where she took on roles of increasing responsibility, culminating in position of head of quality operations at the Merck North Carolina facility. She holds a B.S. in chemistry from Xavier University, and a Ph.D. in organic chemistry from the University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill.

Marla A. Phillips, Ph.D., joined Xavier University in 2008 as the director of Xavier Health, where she leads initiatives with FDA officials and pharmaceutical and medical device professionals. Phillips began working in the pharmaceutical industry for Merck in 1996, where she took on roles of increasing responsibility, culminating in position of head of quality operations at the Merck North Carolina facility. She holds a B.S. in chemistry from Xavier University, and a Ph.D. in organic chemistry from the University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill.